Happy Friday Friends,

I had big plans for this newsletter.

I had wanted to start with some lighthearted ribbing about the near-ubiquitous transference of the feast of the Ascension to Sunday, and the havoc this wreaks with the celebration of the Pentecost novena — the oldest novena and the only one formally prescribed by the Church.

And I planned to round off by making some playful observations about the demented technocrats’ jamboree that is the World Economic Forum in Davos, where speakers un-self-consciously propose the kind of ideas that seem calculated to lend moral, though not literal, truth to the conspiracy theory that we are governed by a global cabal of shapeshifting lizard people.

But I ended up writing about none of that.

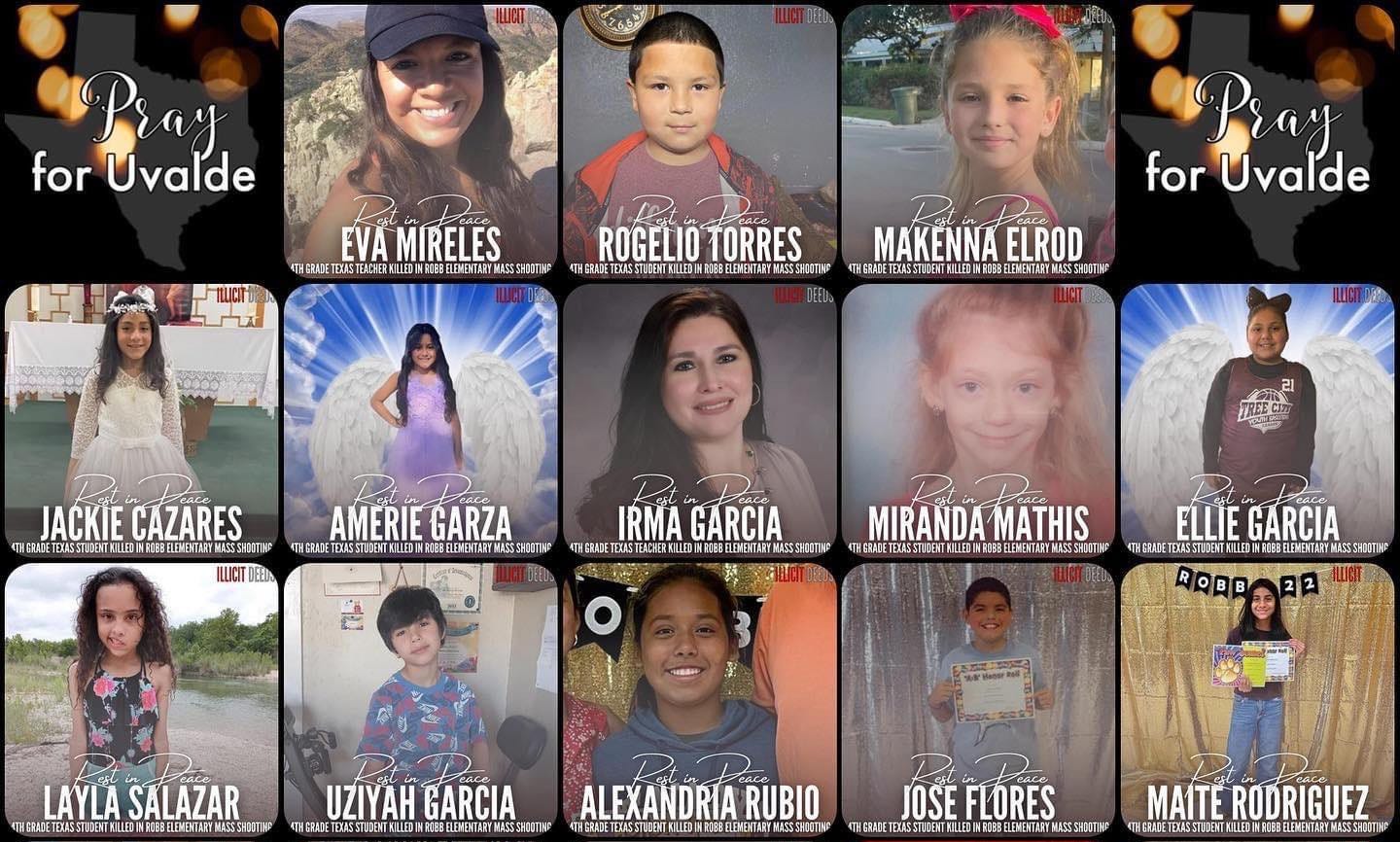

Instead, we had the atrocity of Uvalde, Texas, where 19 children and 2 adults were murdered inside Robb Elementary School.

Everything else seems frivolous in the shadow of such an event, a shadow made darker by the still fresh horror of the racist killing spree in Buffalo not even two weeks ago.

Much of our coverage this week followed on from these events, and there’s much to discuss.

So, here’s the news:

In Venezuela, a priest is facing the prospect of prison, for speaking out against hundreds of execution-style police killings, and calling for an investigation into a state police force and a politician close to Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro.

Fr. Alfredo Infante, SJ, helped publish in March an investigation into 1,414 extrajudicial police killings in his country last year.

Infante and his lawyer spoke to Edgar Beltrán, writing for The Pillar, about his prospects and the lack of due process he is facing.

“Almost 100% of the victims are young, poor males,” he told us. “It seems that for law enforcement, being a young, poor man is being a criminal.”

“As a man of faith, I am inspired by the sacred commandment: ‘Thou shall not kill.’ The Church will keep its voice and action in favor of the victims, and [in favor] of re-establishing the rule of law,”

—

Religious orders are dealing with the same kind of drop in vocations.

It’s an especially pressing question for orders like the Sisters of Mercy, who have an enormous footprint, historical and institutional, in the field of medical care and education.

This is an interesting conversation, and it highlights the kind of thinking about mission, legacy, and transition going on in a lot of institutions founded by religious orders in this country.

—

In 1999, Jim Beckman was a youth minister in Littleton, Colorado, just down the street from Columbine High School. When he heard there was a shooting at Columbine on April 20, he jumped in his car and rushed to the high school.

In the hours that followed - and the weeks and months after that - Jim found himself ministering to teens and families who had been through unimaginable horrors. He wasn’t quite sure what ministry after a mass shooting should look like. He hadn’t been prepared for a situation like the one he faced. But he did what he could, offering food and comfort and hope.

Mostly, he said, he tried to be present.

In the wake of Uvalde, The Pillar talked with Beckman this week, about his memories of the Columbine shooting, and about ministry in a time of violence and tragedy. You can read that conversation here.

The ‘darkness’ and our children

After the killings in Uvalde, Bishop Daniel Flores of Brownsville, Texas, tweeted that Americans “sacralize death’s instruments, and then are surprised that death uses them.” It got a lot of attention, and a lot of people reported on the tweet.

Here’s what he said on Twitter:

And here’s what he told us about that:

“It is a strong statement, but we do sometimes speak about things that way, and I must say that in some sense, we have kind of sacralized the whole idea of the individual right, such that it trumps any communal concern. It becomes an untouchable aspect in the discourse, that the common concern for the good of the vulnerable is not in any way sufficient to limit the individual right to determine whether or not I want to own this kind of a gun, or that kind of gun, or, you know, a hand grenade for that matter.

So when you sacralize it, you kind of make it basically closed for discussion, because we practically treat it as if it were sacred.

And that’s a strong phrase, but to a certain extent, I think there’s an analogy here. It’s not the same thing, but that’s the thing about an analogy: it’s not the same thing.”

Flores went on to talk about the risks our culture poses to the mental and spiritual health of young people, which is certainly related to the mass shootings we have seen in recent weeks, and the urgent mission of the Church in all of this:

“From the deeper Catholic theological position, you know, both nature and the human soul abhor a vacuum. And a lot of young people kind of feel an emptiness inside of them.

So I encourage young people to cultivate your sense of the presence of God in your life. And pursue those, be strong in goodness, because neutral territory is vulnerable territory.”

But there’s more - a lot more - and it’s worth reading in full.

The prophetic and the pragmatic

Despite what you might hear, the bishops of the United States talk a lot about gun violence, and often lend their support to proposed laws aimed at curbing it. Nevertheless, it’s a common misconception — fueled by a common accusation — that the Church doesn’t care as much, or lobby as hard, about gun violence as it does against, say, abortion.

They, like everyone else in society, have to work with the legitimate right of self-defense, and balance it against the needs of the common good in the face of violence. And they have to do so in vastly different circumstances in different states.

One thing we learned from the conversation was how state Catholic conferences are taking lessons from the abortion debate and applying them to legislative conversation about guns.

As one of state leader explained, as with abortion, national polling on guns gives some often misleading headline statistics, but when you drill down just a little you find a broad base of consensus around certain limits people support. And, as with abortion, there often just isn’t the political will to enact them.

It’s about the context

I only returned to live in the United States as an adult in my mid-thirties, and I never feel more like a foreigner in my own country than after one of these horrible events.

I confess upfront that I have never felt drawn by a particular “side” in the gun debate, at least apart from in the immediate context of 19 children being murdered in their classroom.

I own no handguns or rifles, I have no desire to do so, and I’m mystified by the sine qua non significance often placed upon them in American discourse of rights. That said, as a lawyer and a journalist, I hear the concern about how the case against the Second Amendment — that its authors couldn’t conceive of modern firearms — might be applied to the First Amendment, which obviously did not foresee the internet either.

That all gives me pause, or it would, were it separable from the immediate context of 19 children being murdered in their classroom.

I also understand that, as all the statistics I have seen seem to show, there would appear to be no obvious evidence that cities and states with stricter firearms laws necessarily have less gun crime, and that legal gun owners are, statistically speaking, more law abiding than average.

And I am sensitive to the reality of a “gun culture” in many parts of this country which is not sinister, and indeed places a premium on responsibility, of which I have no personal experience and which I should refrain from judging in my ignorance.

Or I would be, outside of the immediate context of 19 children being murdered in their classroom.

The problem I have in all of this is the immediate context of 19 children being murdered in their classroom, barely a week after 10 people were gunned down in a supermarket because they were Black.

And that both of these atrocities were carried out by teenagers with obvious warning signs of mental instability who still had, so far as I can tell, legal access to firearms — one in a very loosely regulated state (Texas) and the other in one of the most strictly regulated (New York).

I simply do not know how to process this other than as an existential civilizational crisis.

Still less can I fathom what seems to me like the neatly patterned normality of these mass shootings in the public life of this country, from the formulaic press conferences to the oven-ready point-counterpoint to assign political blame.

It boggles my mind that apparently otherwise sane people are prepared to propose that schools be secured and guarded like super-max prisons as the necessary condition of preserving a “free society.”

I cannot but recognize the same irrationality, the same obtuseness, the same inhumanity, in much of the pro-gun discourse after these atrocities as we see so often in pro-abortion arguments.

Indeed, the two realities seem obviously linked — we are a society which has normalized the mass killing of its children as a (most regrettable) byproduct of our conception of freedom and rights. This is our wider context, an individual absolutism that cedes nothing to the needs and good of the vulnerable, and I see no prospect of this changing.

It seems inescapable to me that a society which has so internalized and normalized violence, and at the same time warped and sabotaged the basic concept and worth of family, must result in a generalized crisis of mental health — the acute extremes of which appear to be at the center of these mass killings. This is, surely, the picture of a culture of death whose first victims are, inevitably, its children.

To be clear: it is not my opinion that gun ownership should be generally criminalized as a matter of course, any more than I would think that prenatal healthcare should be. But when either become sufficiently weaponized, literally, for the taking of innocent human life, I see every imperative to act somehow.

But, with the expectation that Roe v Wade is soon to be repealed, we are likely to face the same reality on abortion as we currently do with guns: that statewide laws can do some things, save some lives, but cannot do everything, or save everyone. And even if national legislation were an option, both abortion and guns are too freely available, too deeply ingrained in our society, to be effectively removed from our cultural bloodstream in a hurry.

Friends smarter and more familiar with the American political and legal systems than I assure me that it would take a constitutional amendment to truly resolve either issue. And that is impossible. It is impossible for the same simple reason that it is necessary — we are no longer the kind of coherent society that ratified the Bill of Rights in the first place and which is required to change it.

What then is the answer? Politically and legally, I have no idea, though I mostly subscribe to Carle Zimmerman’s conclusion that a society which has sufficiently disintegrated the family and atomized the individual is sure to collapse.

For myself, I see only the bleeding void at the centre of our culture that cries out for Christ, for the love of the other to the point of death. For the truth of the resurrection.

As we learn more about what unfolded this week at Robb Elementary, I am as filled with rage and despair and righteous anger as anyone else. But woe to me if I do not announce the Gospel.

See you next week,

Ed. Condon

Editor

The Pillar