The book of before and after

How a priest is bringing an Eastern breviary to English-speakers — and why.

In the 21st century, the ancient Chaldean Catholic Church is a truly global institution. The Eastern Church has spread far beyond its Iraqi homeland, to Europe, Oceania, and North America.

The diaspora community’s growth poses serious challenges for the transmission of the Church’s faith and heritage. A young Chaldean Catholic growing up today in Detroit or San Diego may feel more at home in English than in their paternal language, Chaldean.

Fr. Andrew Younan, the first American-born Chaldean Catholic priest, feels a deep responsibility to keep the dialect of Neo-Aramaic alive. At the same time, he wants to introduce English-speakers to the Eastern Church’s deep life of prayer.

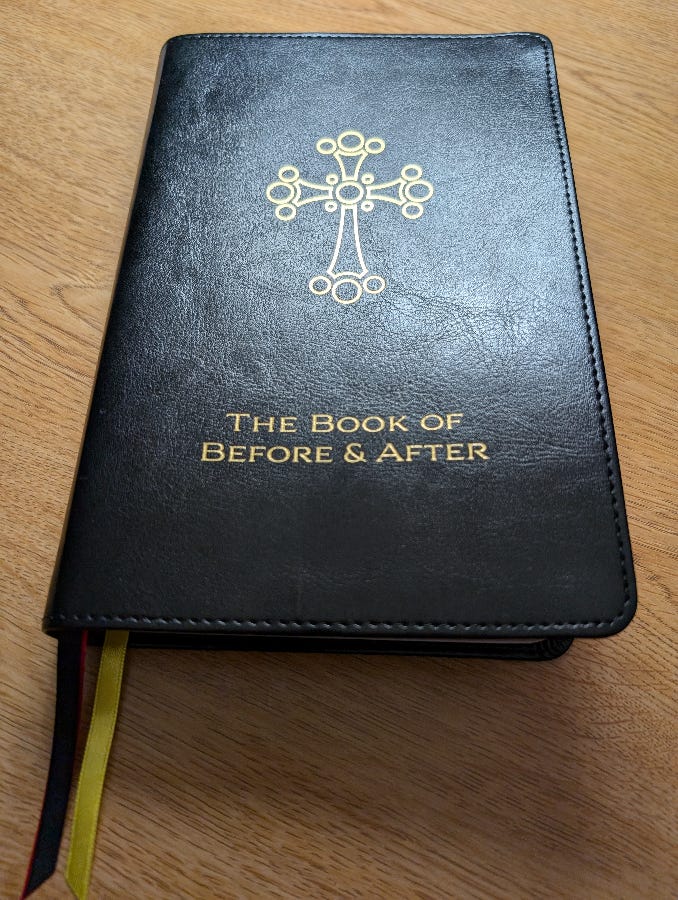

That’s why he has published “The Book of Before & After,” a groundbreaking English translation of the liturgy of the hours of the Church of the East that was decades in the making.

The liturgy of the hours — also known as the Divine Office or breviary — are the daily prayers recited at regular intervals by priests, religious, and countless laity worldwide.

The Church of the East is the Christian community established to the east of the Roman Empire by St. Thomas the Apostle, with his companions St. Addai and St. Mari, and using Aramaic, the language spoken by Jesus, in its liturgy.

Four present-day communities — the Chaldean Catholic Church, Assyrian Church of the East, Ancient Apostolic Assyrian Church of the East, and Syro-Malabar Catholic Church — are rooted in the Church of the East.

In emails with The Pillar, Fr. Younan, a member of the Chaldean Catholic Eparchy of St Peter the Apostle, discussed the art of translation, how to begin praying the liturgy of the hours, and the “crisis” facing the Chaldean Catholic Church — as well as mandolins and misanthropy.

You describe the “Book of Before & After” as “an attempt to render into English, for the first time in a form ready for the use of the faithful, the liturgy of the hours of the Church of the East.” How did you envisage that Catholics will use the book?

We pray morning and evening prayer with earlier editions of this book in several parishes in our eparchy, every day of the week.

It’s very enriching to a parish to provide access to these prayers, perhaps before a daily (or Sunday) Mass [Divine Liturgy], so that parishioners who can make it to Mass a little early can experience some of the beauty that sanctified their forefathers.

Beyond parish usage, these books can easily be used by religious communities, during retreats, or even among friends praying together. It is also quite common for people to pray the liturgy of the hours on their own, and even if they aren’t singing by themselves, the words are theologically and spiritually rich, and can help form a deep life of prayer.

There’s an accompanying website with the book’s melodies. Why was it important to offer this as well?

The biggest challenge in this translation was to render Aramaic hymns into English that keeps the same (or a similar) syllabic structure, so that the hymns can be sung in English with the same melody they have in Aramaic.

There are dozens of different melodies for these hymns, and the music of the liturgy is such an enormous part of its beauty, so we created the website so people everywhere can learn the melodies and sing with the ancient melodies as they use this book for prayer.

What is the book’s intended audience?

It’s really for two groups. First, it’s for the faithful to be able to pray in this tradition and keep it alive.

Second, it’s for scholars and readers interested in liturgy and the Eastern Churches, to encourage interest in liturgy (which is often neglected by scholars) and in the Eastern Churches (which are often neglected in general).

Are there a lot of English-speaking Chaldean Catholics who are disconnected from the patrimony?

There are hundreds of thousands of Chaldeans living in “the West.” Some of them speak their paternal language, and I work very hard to produce books and videos to keep the Chaldean-Aramaic language alive.

At the same time, the prayers of the Church of the East should not be reserved only for those who know a particular language, so translating as much of it as possible so that English-speaking people have access to them has been a high priority for me for much of my life. In fact, I’ve observed that praying in their tradition inspires a lot of people to learn their language.

What are the consequences of a rise in Chaldeans who only speak English? Is the Chaldean Church changing in some ways as a result?

There is a serious crisis on the horizon of the Chaldean Church, which is somewhat hidden because Chaldeans are generally fairly faithful and our churches are pretty full.

The crisis is that within a lifetime, the Chaldean Church could very easily disintegrate as its people either stop being religious or go to other churches. The temptation in the West right now is to make short-term “gains” by making ourselves as much like the Latin Church as possible (“latinization”), adopting their style, music, etc.

This is, in my experience, an easy way out that will be suicidal in the long run. If the Chaldean Church ends up feeling just like a Latin Church, then why not just go to a Latin Church?

The more challenging route is to take our traditions, prayers, music, and spirituality, and make them accessible to the English-speaking faithful. This route is more work and has more social obstacles, but in my view it’s the only real way to keep the Chaldean Church alive in the long run.

What would your advice be to a Catholic who’s interested in starting to pray the liturgy of the hours?

Do it. The liturgy of the hours is the official daily prayer of the Church, and will deepen your prayer life immensely. But it takes some discipline, so I’d advise starting with a short and simple morning and evening prayer every day, and giving yourself a few weeks or months to get into the rhythm of it. After that, expand to a longer form of prayer.

What I mean by “short” and “long” forms are (for example) what can be found in the Latin Church’s “Shorter Christian Prayer,” then moving to the more common breviary titled “Christian Prayer,” then getting the full four-volume set of the Liturgy of the Hours.

In the case of the Church of the East, there are three versions of the liturgy of the hours contained in the new prayer book. You can start with the “shorter” prayers which begin on page 243, then move eventually to the “Emmanuel” prayers which start on page 141, and are really well-suited to parish or individual prayer. The book also has the full traditional set of prayers starting on page 1. I discuss this, and how to use the book, in this video:

It’s also worth noting that both the shorter versions of the prayers and the Emmanuel versions are available on a very handy and easy-to-use phone app.

Would you encourage Latin Catholics to use “The Book of Before & After?”

Strictly speaking, no. [Eastern] canon law really prefers people to pray according to their own rite, and forbids people from pressuring others to change rites.

On the other hand, if a Latin Catholic finds that they like praying with this book, there’s nothing to stop them, and prayer is always a good thing.

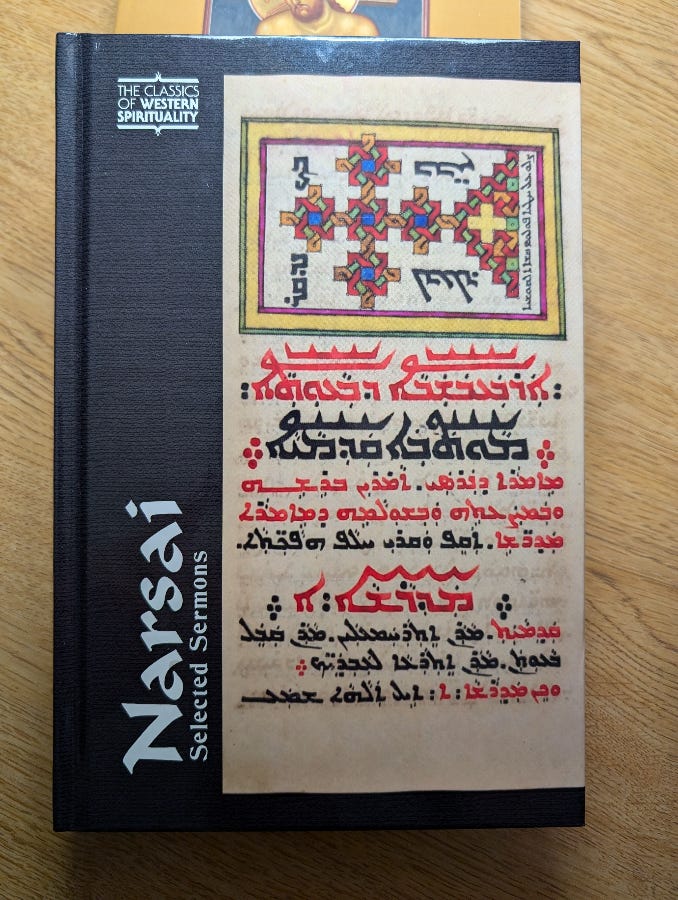

You also have a new book on the sermons of St. Narsai, a giant of Eastern Christianity. What made you write this book?

This book was another decades-long dream of mine that happened to come out at the same time as the prayer book. Narsai is a deep, poetic theological thinker that has thankfully been given more attention by scholars in the last decade or two, and I’m part of a group of scholars working on translating all of his works into English.

My volume is meant to be an introduction to his thought, more accessible to non-experts, and I hope it helps spark even more interest in him.

How did you come to be the Chaldean Catholic Church’s first U.S.-born priest?

By accident, I think. There just hadn’t been very many ordinations before me because the Chaldean community was relatively new in America. Bishop Francis Kalabat was ordained nine years before me and he grew up in America, but was born in Kuwait. There were no ordinations between his and mine in the whole country, while now (thank God) we have newly ordained priests both in the Detroit and the San Diego eparchies basically every year.

If you’re asking about my vocational calling, it came through a gradually growing love of God and a feeling that I wanted to serve and help my community, and through a special love of my liturgy.

As well as being a Chaldean, a priest, a seminary rector, a philosophy professor, a cat owner, and an octave mandolin player, you are also a self-declared misanthrope. Is it hard to fit in misanthropy alongside your many other interests and activities?

I need to update my social media bio. My cat Siduri now lives with a nice family due to some allergy issues at the seminary. I’m also now a chorbishop (analogous to a monsignor), and I’ve never been very good at mandolin but I can pluck away when needed. Misanthropy is both a personality trait and a requirement for me to keep up with everything else I do.

Being rector of the seminary is an extremely demanding and mentally taxing ministry, not exclusively because of long hours of work but because of the responsibility that comes with it. Some of the men in my care will end up as priests for the Church, and we who work with them on their formation are responsible for making sure they are the best priests they can be. A small failure on our part, or neglect, or a missed red flag, could be absolutely disastrous for the Church when they end up serving as priests. In comparison, teaching philosophy is a welcome break.

I’ve read that the Chaldean Catholic community in California is thriving. Is that accurate?

We have our moments. Our eparchy encompasses the whole western United States, and we have parishes throughout California, as well as in Arizona and Nevada, and a mission in Texas. In many ways we are thriving, yes, and I’m very proud of what our people have accomplished.

If I can, I’d like to ask your readers to pray for my bishop and my brother priests here and in the Detroit Eparchy. We live lives of joyful service, but we all need God’s grace to make it through the day.

What inspired you to begin work on “The Book of Before & After?”

I’ve been working on pieces of this book since I was a deacon more than 20 years ago, and published what I could call a much shorter first draft of it all the way back in 2008, with other editions in the intervening years.

I joined the seminary and learned about the liturgy of the hours, and how enriching they are to pray; I then learned the dialect of Aramaic needed to read and pray my own liturgy of the hours — called the Ḥudhra, or “Cycle” — and began praying on my own, and absolutely fell in love. After that, I realized that these prayers were a treasure that should be shared, and that sharing them meant translating them.

My first translations were clunky, and I constantly struggle with the feeling that I’m doing violence to something beautiful when I translate, but this latest edition is something that, I hope, gives a real taste of the spirituality of the Church of the East to English-speaking people.

"[Eastern] canon law really prefers people to pray according to their own rite, and forbids people from pressuring others to change rites."

I'm curious about this—I imagine these rules are in place mostly as a guard against Latinization of the Eastern faithful, but at the same time, doesn't insisting that people pray according to their own rites hinder Latin Catholics from coming to better understand and appreciate that part of the Church? Perhaps more broadly, what are we to make of the phenomenon of young Latin Catholics taking a strong interest in Eastern prayer and liturgy?

Regardless of the answers to the above questions, this was a fascinating interview, and I hope many people take to praying with Fr. Younan's translation. It's also quite refreshing to hear that he takes his duties as a seminary rector quite seriously, and I appreciate his willingness to admit misanthropy—between that and his translation efforts he's in good company with St. Jerome, which is pretty solid.

Wow, this is an impressive man. The American (Latin) church could use a hundred more like him: articulate, intellectually curious, scholarly but down to earth, psychologically well adjusted (by all appearances), and dedicated to his work. Better still, he is, like me, a frustrated mandolin player. I'd be happpy to purchase "The Book" on Amazon, to support his work; if there is another way to purchase it by which he/his church gets more of the profits, I'd be happy to know that. Please continue to cover his church community.