July 3, 2024, was supposed to be the day that the decades-long liturgy dispute in the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church finally ended.

Not with a compromise, but with a declaration that hundreds of priests had fallen into schism by refusing to accept a new Eucharistic liturgy by the July 3 feast of St. Thomas, the apostle considered the Eastern Church’s founder.

But this intricate and often chaotic dispute doesn’t seem to be heading for a neat ending.

And perhaps that’s not surprising. After all, the disagreement was never solely about which way the priest should face during the Holy Qurbana, as the Eucharistic liturgy is known in the Syro-Malabar Church.

It was also about how authority is exercised in a synodal Church, the tension between uniformity and diversity, and the profound consequences of a breakdown in trust.

None of these matters can be resolved by setting a deadline and threatening severe penalties for failure to comply. They take years of painstaking effort. And even then, they often arise again in different forms.

How we got here

First, a quick reminder of how we got here. The Syro-Malabar Church is the second-largest of the 23 Eastern Catholic Churches in full communion with Rome after the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church.

Priests in this ancient Eastern Church, based in Kerala, southern India, originally celebrated the Eucharistic liturgy facing east (ad orientem).

Following centuries of contact with the Latin Church and the liturgical reforms introduced after the Vatican Council II, clergy began to celebrate the liturgy facing the people (versus populum).

The synod of bishops — the autonomous Eastern Church’s supreme authority — was concerned that these liturgical divergences undermined the Syro-Malabar Church’s unity.

In 1999, the synod approved a compromise known as the “50:50 formula,” in which the priest faces the people during the Liturgy of the Word, turns toward the altar for the Liturgy of the Eucharist, and faces the people again after Communion.

Despite Vatican support, the “uniform” liturgy was not universally adopted. In 2021, the synod of bishops asked all of the Syro-Malabar Church’s 35 eparchies (dioceses) to accept the new Eucharistic liturgy by November that year.

Most complied, but there was mass resistance in the Archeparchy of Ernakulam-Angamaly, the Eastern Church’s most populous and prominent diocese, which had seen a “priests’ rebellion” in 2017 over contentious land deals by Church authorities.

Most of the archeparchy’s 655,000 members wanted to retain the liturgy versus populum, which they had celebrated for more than 50 years.

For the past three years, Syro-Malabar Church leaders have sought to impose the new liturgy on the archeparchy through a succession of deadlines backed by threats of canonical disciplinary action, with the support of Vatican officials and Pope Francis.

As tensions increased, so did the archeparchy’s resistance. Supporters and opponents of the uniform liturgy clashed in the streets. Priests went on hunger strikes, lay people burned cardinals in effigy, police were called to a scuffle in the sanctuary of the archeparchy’s cathedral, which remained closed for more than a year.

In December 2023, Pope Francis overhauled the leadership of the Syro-Malabar Church and the Ernakulam-Angamaly archeparchy, seemingly in a fresh effort to resolve the dispute.

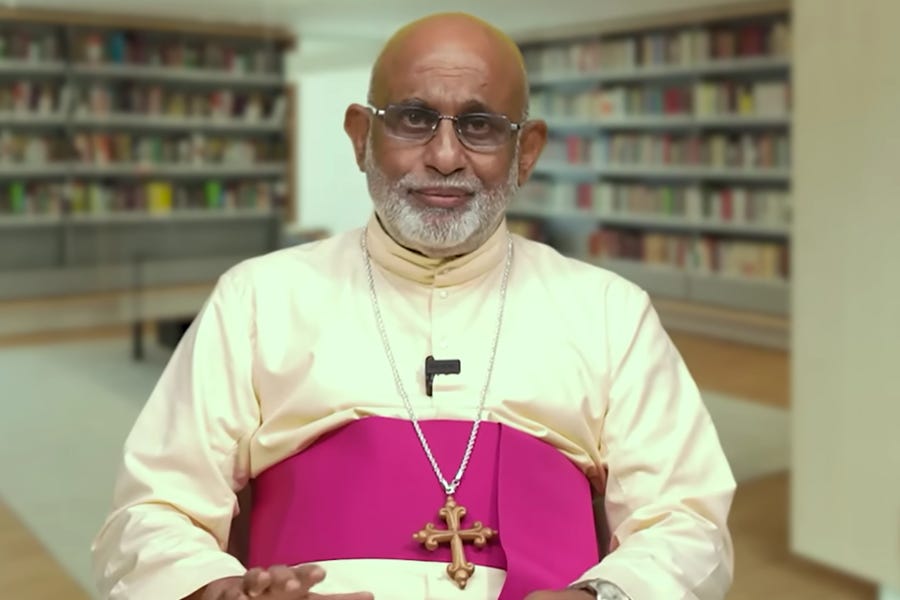

Soon after his election, the Eastern Church’s new leader, Major Archbishop Raphael Thattil, sought to impose the new liturgy on the archeparchy through a deadline backed by threats of canonical disciplinary action.

Thattil and the archeparchy’s new apostolic administrator Bishop Bosco Puthur declared in a June 9 joint circular letter that priests who refused to adopt the new liturgy by July 3 would be considered to be in schism and barred from priestly ministry.

The new uniform liturgy is celebrated at St. Thomas Church, Shanthipuram, in Kerala, southern India.

Weeks of tumult

A great deal has happened since the publication of the June 9 letter.

Here’s a quick summary of the developments:

In a leaked June 13 letter to Major Archbishop Thattil, five Syro-Malabar bishops expressed firm opposition to the threat to excommunicate priests.

A June 14 online meeting of the synod of bishops called to address the liturgy dispute failed to reach a conclusion.

Only seven out of 328 churches in the archeparchy complied with a request to read out the circular letter on Sunday, June 16. Lay people were filmed burning copies of the letter and even turning it into paper boats and setting it adrift on Kerala’s Vembanad Lake.

Fr. Kuriakose Mundadan, secretary of the presbyteral council of the Ernakulam-Angamaly archeparchy, appealed to India’s Latin Catholic bishops to intervene in the Syro-Malabar Church’s liturgy dispute.

The synod of bishops resumed its online discussion June 19. A day later, reports emerged of a surprise breakthrough with the potential to end the dispute.

The tentative agreement appeared to collapse after the publication of a June 21 post-synodal note signed by Major Archbishop Thattil and apostolic administrator Bishop Puthur, upholding the threat of punishment for failure to comply with the deadline.

In a July 1 explanatory note, Major Archbishop Thattil and Bishop Puthur said that all parish churches in the Archeparchy of Ernakulam-Angamaly could continue celebrating the liturgy versus populum after July 3 provided they offered at least one new uniform Eucharistic liturgy on Sundays and major feast days.

Where have these weeks of tumult left the Syro-Malabar Church?

Crisis averted?

As things stand, the scenario in which more than 400 priests of the Ernakulam-Angamaly archeparchy are declared to be in schism has been averted.

This is thanks to the July 1 explanatory note, issued on the eve of the deadline, conceding that parishes can continue to celebrate the Holy Qurbana versus populum, provided they offer minimal recognition of the uniform liturgy.

According to the Archdiocesan Movement for Transparency, which represents priests, religious, and laity opposed to the new liturgy, the compromise emerged from two days of discussion at the Syro-Malabar Church’s headquarters at Mount St. Thomas.

In practice, not all parishes in the archeparchy are expected to provide the uniform liturgy immediately. Churches where the congregation has clearly expressed its opposition, for example, won’t be required to introduce it, pending further discussions.

Early reports suggest that July 3 passed peacefully in the archeparchy. According to Indian media, 250 out of 321 churches celebrated a uniform liturgy.

The uniform liturgies reportedly saw low attendance, while liturgies versus populum drew large numbers.

What’s next

Major Archbishop Thattil and Bishop Puthur’s explanatory note included an undertaking that the synod of bishops would consult with the archeparchy’s advisory council, presbyteral council, and pastoral council before taking further actions concerning the liturgy.

Opponents of the new liturgy are hopeful that the synod of bishops will now pursue ways of permanently resolving the crisis, in consultation with those most affected by the dispute.

But they also retain a lingering suspicion of the synod, because they believe that it has reneged repeatedly on agreements.

The Archdiocesan Movement for Transparency has said it will continue to press for the liturgy versus populum to be recognized as the official mode of celebration in the archeparchy and for “restitution” following the land deal controversy.

Those demands show that the underlying differences have not been settled, despite the last-minute agreement to avoid a split in the Eastern Church.

Meanwhile, the Syro-Malabar Church as a whole is changing rapidly. Since the turn of the millennium, it has established itself successfully far beyond the borders of its homeland in India’s southern Kerala state.

Due to migration, it is now a global body with dynamic congregations in Europe, North America, the Middle East, and Oceania. As Pope Francis put it in a May address to a Syro-Malabar group led by Major Archbishop Thattil, “the faithful of your beloved Church are known, not only in India, but throughout the whole world, for the ‘vigor’ of their faith and piety.”

But as the diaspora grows and bishops in Kerala struggle to persuade young Catholics to remain in India, questions about the Church’s complex identity become more pressing.

What is essential to that identity and what is merely contingent? Does the Syro-Malabar Church need to do more to recover its ancient Eastern identity? Or should it accept that centuries of Latinization has left it with a permanent Western imprint?

These might sound like abstract questions, but they might be important if you are, say, the child of Syro-Malabar parents from India growing up in a suburb of Chicago or Sydney, surrounded by Latin Rite Catholics.

They are also the questions that appear to lie behind the Eastern Church’s “liturgy wars.” It seems that where there are disagreements about identity, there will also be disputes about liturgy.

Unfortunately, these are so complicated that they cannot be resolved with circular letters or explanatory notes, or even resolutions from synods of bishops or papal interventions.

They can only be worked out — slowly and sometimes painfully — within the roughly five million-strong Syro-Malabar community in the coming years, decades, and probably even centuries.