Does Francis’ female prefect square the circle on lay governance?

The appointment of a cardinal pro-prefect for the Dicastery for Religious could defuse a long-simmering canonical debate over the link between sacred orders and authority in the Church

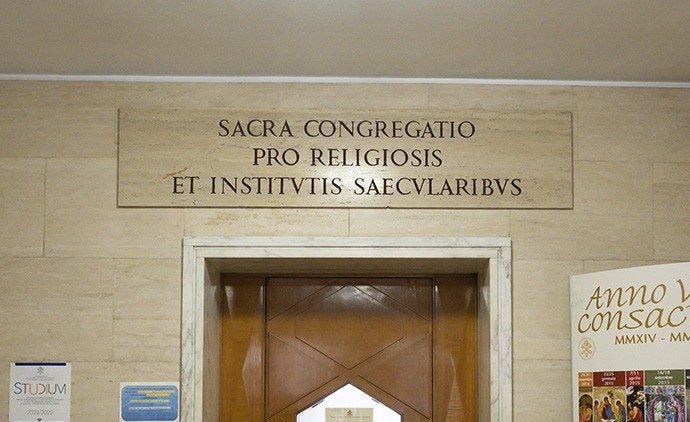

Pope Francis blazed a new ecclesiastical trail on Monday, appointing the first female head of a curial dicastery by promoting Sr. Simona Brambilla, I.S.M.C, from secretary of the Dicastery for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life to become its new prefect.