More than 50 people were killed during Mass on Pentecost Sunday in Nigeria, when a group of assailants attacked St. Francis Catholic Church in Owo, a city in the Ondo state in Nigeria’s southwest.

Dozens are being treated in local hospitals, including at least 13 children, after an attack that involved both explosions and gunfire in the parish church.

Pope Francis promised prayers Monday for victims, and the Diocese of Ondo said June 5 that the situation “has left the community devastated.”

“We turn to God to console the families of those whose lives were lost in this distressing incident, and we pray for the departed souls to rest in peace,” the diocesan statement said, while urging Catholics to “remain calm, be law abiding and pray for peace and normalcy to return to our community, state and country.”

The attack itself was brutal.

Fr. Andrew Abayomi told Morning Star News that:

“We were in Mass when the terrorists attacked us. They shot at the congregation while breaking into the church by throwing improvised explosive devices at the church building.”

“Some of us hid inside the church as they shot randomly at us. This lasted for about 20 minutes before they retreated.”

Lawmakers in the region say the attack was perpetrated by Fulani herdsmen, who have carried out acts of violence in Nigeria’s northern and central regions, but have not generally committed terrorism in the country’s southern states.

But Olayemi Adeyemi, Owo’s delegate to Nigeria’s House of Representatives, told reporters Sunday that:

“The attack was a reprisal aimed at sending a message to Governor Rotimi Akeredolu who chased away violent Fulani pastoralists from the area.”

“Locals around the church premises saw the attackers who were on the run after unleashing the horrific act on the church. They were armed herdsmen of Fulani extraction, a tribe accused of spearheading insecurity across the country,” Adeyemi charged.

Fulani herdsman are believed to be responsible for thousands of death in Nigeria’s Middle Belt, mostly in terror attacks committed against Christian farming communities. But the conflict is complicated: While the Fulani are Muslim, religion is only one aspect of the attacks waged in Nigeria in recent years.

So who are the Fulani? And - if Fulani terrorists are responsible - why would they shoot up a church on Pentecost?

The Pillar brings you a primer on the history of a complex situation, which has become deadly across much of Nigeria.

Who are the Fulani?

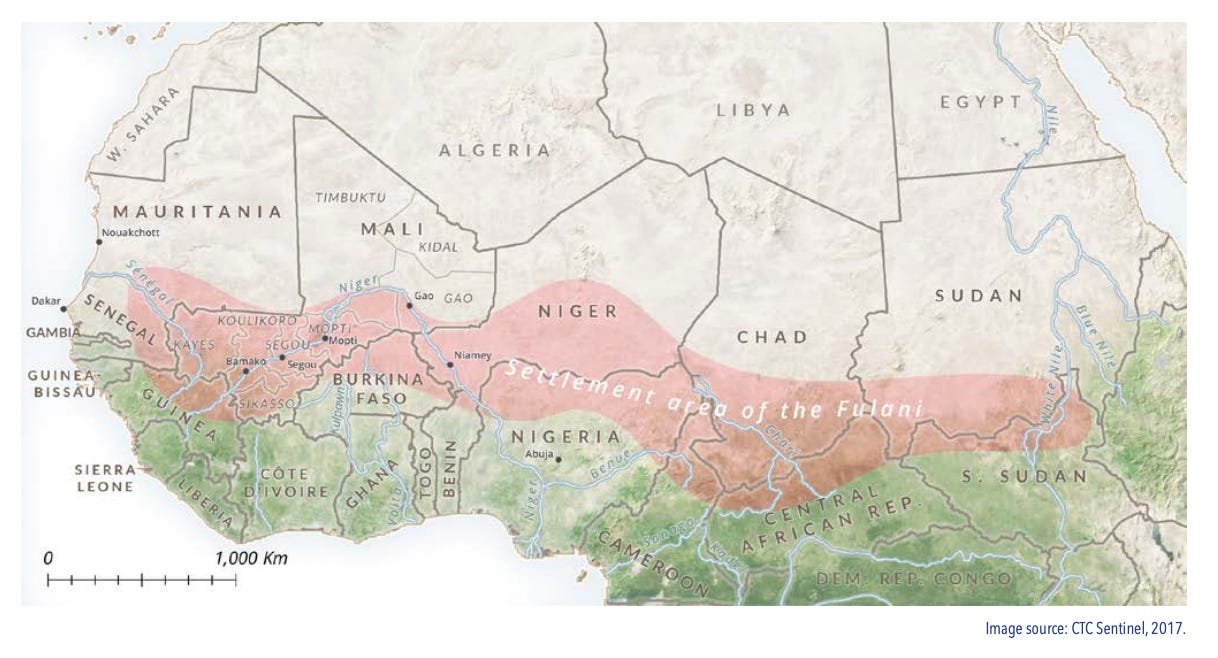

The Fulani people are the largest nomadic tribal, or ethnic, group in the world, and are diffused across much of northern Africa — the Fulani constitute an ethnic minority in every country they occupy.

There are an estimated 25 million people of Fulani ethnicity, most of them Muslim. It is estimated that between 12 and 13 million Fulani are nomadic or semi-nomadic herders of cattle, goats, and sheep, who travel across large areas in West Africa to provide grazing land for their livestock.

As many as 13 million Fulani people live in Nigeria, an estimated 6% of the country’s population — but not all of them are nomadic herders. Many Nigerian Fulani people have migrated to cities, especially as desertification in the country’s northern region has decimated traditional grazing lands.

Why are the Fulani attacking Christians in Nigeria?

That’s a pretty complicated question.

Let’s start with some background about cattle herding and population growth. In recent decades, Nigeria’s population growth and advances in agricultural technology have led to an expansion of agricultural land use in the country’s “Middle Belt,” which was traditionally a kind of no-man’s land between the country’s majority Muslim north and its predominately Christian southern regions.

Much of the agricultural growth has included growth of the region’s Christian population — Christians are now believed to make up nearly 70% of the region’s people, as families from the country’s south have migrated to farm the area.

There have always been clashes at the frontier between agricultural and grazing lands.

But the growth in agriculture in recent decades has cut off access to many traditional cattle migration routes and sources of water, which the Fulani say were once understood by custom to be protected spaces.

At the same time, Fulani herding groups have moved southward because of the desertification of their usual grazing lands, which is exacerbated by climate change.

Advances in veterinary medicine also make it possible for Fulani herders to push their livestock further into southern Nigeria, where they once were more susceptible to disease, into areas where beef commands higher prices. That push has created new tensions among farmers and herders, in regions where they were not seen until recent decades.

Many Fulani leaders say that if they don’t preserve their nomadic way of life, and the grazing lands and migration routes that go along with them, they’ll lose a generation of young people, who are drawn to cities — even when the economic opportunities of those cities are very limited.

But there is no singular approach to addressing that problem among the Fulani, and violent attacks on Christian farmers have been condemned by most Fulani leaders in Nigeria.

Still attacks have become frequent. Violence flared up in the early 2000s, when Fulani herdsman attacked farming communities they accused of stealing their cattle and blocking their routes. At the same time, farmers - who claimed their land was being trespassed and their crops trampled - attacked herdsmen.

But Fulani retaliation became increasingly brutal and - according to analysts in the region - led to the destruction of villages, the burning of churches, to massacres and acts of sexual assault.

And amid escalating tension, observers in the region say that Boko Haram and other Islamic militant groups have armed young Fulani men, framing economic and political disagreements as religious clashes, and urging more violence.

But this is clearly a religious conflict, right?

That depends on who you ask.

The Fulani are Muslims, and the people killed, kidnapped, tortured, and raped by Fulani terrorists in Nigeria have been predominantly, but not exclusively, Christians. The conflict is often framed in religious overtones, and is both fueled by, and fuels, religious conflict.

But the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom said in 2020 that “experts and practitioners continue to debate the extent to which religious ideology plays a direct role in driving violence involving Fulani communities and individuals in west and central Africa.”

Still, the USCIRF said the violence is “aggravating religious tensions in countries like Nigeria and the Central African Republic.”

Noting that the violence “continues to exacerbate Muslim-Christian tensions,” the USCIRF explained that in Nigeria’s Middle Belt, most narratives about the causes of the violence involve religion.

Indeed, some Middle Belt and Christian leaders have said the aim of Fulani herdsmen terrorists is to impose Islamic law on the region, and the language of Islamist expaisionism has been used among jihadistist groups providing arms to groups of Fulani terrorists. Further, in the Middle Belt, churches have been targeted for violence, priests and religious have been kidnapped, and Christians have faced sexual violence by Fulani terrorists.

The USCIRF points out, though, that some analysts have found “that religious ideology plays only a minor role in the motivations of most Fulani fighters, even those associated with jihadist groups.”

Still, those analysts have found “common objectives between Fulani fighters and Islamic extremists include overthrowing regional governments, disrupting the perceived inequitable status quo and distribution of resources, and pilfering from illegal mining and trafficking activities.”

The USCIRF explains that “in general, jihadist groups and ideologies reportedly do not enjoy much popular support in Fulani-majority areas.”

Earlier this month, Archbishop Matthew Man-Oso Ndagoso, who leads the Kaduna archdiocese in the Middle Belt, insisted to Aid to the Church in Need that the conflict is not a religious one, even while it has taken on religious overtones.

Ndagoso blamed government inaction for continued attacks, and said the language of religious conflict was a convenient but simplistic account of the violence.

“In the northwest the farmers are mostly Muslims, and they also have conflicts with the Fulani. As you move to the middle belt, it is inhabited mostly by Christians, so there it will most likely be a Christian farm. Religion and ethnicity are very sensitive problems in Nigeria, they are always used for convenience, but primarily this conflict is not religious, I am absolutely sure,” Ndagoso told Aid to the Church in Need.

“If you apply for a job and you don’t get it, you might say you were rejected because you are a Christian, and the same for Muslims. Opportunists, such as politicians, use these factors to their own advantage, but if you go to the root, you discover it is little or nothing to do with religion,” the archbishop said.

“This is not to say that there is no religious discrimination in Nigeria,” he added.

The archbishop lamented “systemic” religious persecution of Christians in the country’s north — but he attributed that to state policies, not the Fulani, and urged Christians to push for reforms.

In many northern Nigerian states “they do not allow the teaching of Christianity, yet the government employs and pays Imams to teach in schools. Every year they have money to build mosques in the budget but will not let you build churches. In my state there is a university and across the street there are five mosques, no church. We wanted to build one, they didn’t allow it. If you build a church without permission, the government can tear it down. This is what we are going through. It is serious. We want our government to be held accountable, for people to be treated equally,” he said.

“In the last elections there was voter apathy, people lost confidence in the system. As a leader I must give people hope. We hope that with electronic voting the transmission of results will be safer and therefore people will come out en masse to vote. Four years ago, we summarized Catholic social teaching, about the common good, and we have been using it to raise awareness. In recent months there have been by-elections, and the electorate has become wiser, they are not just choosing anybody. Using the Catholic social teaching we have shown that you must hold people accountable,” he said.

How much violence has there been?

Fulani terrorists are regarded as responsible for tens of thousands of deaths in Nigeria since 2009, most of them Christians, but also Muslims from farming communities in Nigeria’s northwest.

The violence has moved further south in recent years, with the Pentecost attack - if it was perpetrated by Fulani terrorists - being one of the southern-most acts of Fulani terrorism.

In recent months, other Nigerian churches have been attacked by Fulani terrorists, with parishioners either being kidnapped or shot by terrorists.

Nigerian Christians also face attacks and kidnappings by the Boko Haram terrorist movement. According to Genocide Watch, between 400 and 420 churches were attacked in 2021, and more than 5,000 Christians were killed in the country by Fulani terrorists or Boko Haram last year.

Genocide Watch reports that nearly 1,000 Nigerian Christians were killed in the first three months of 2022, and more than 3,800 Christians were kidnapped in the country.

President Muhammadu Buhari condemned Sunday’s killings and has - as he has in the past - ordered a manhunt for the perpetrators of the attack.

Thankyou for that report. It's the most unbiased that I've read in the last 24 hours and I appreciate that.

What a complicated situation. People in America (including me) are ignorant on most of Africa. Thanks for the education