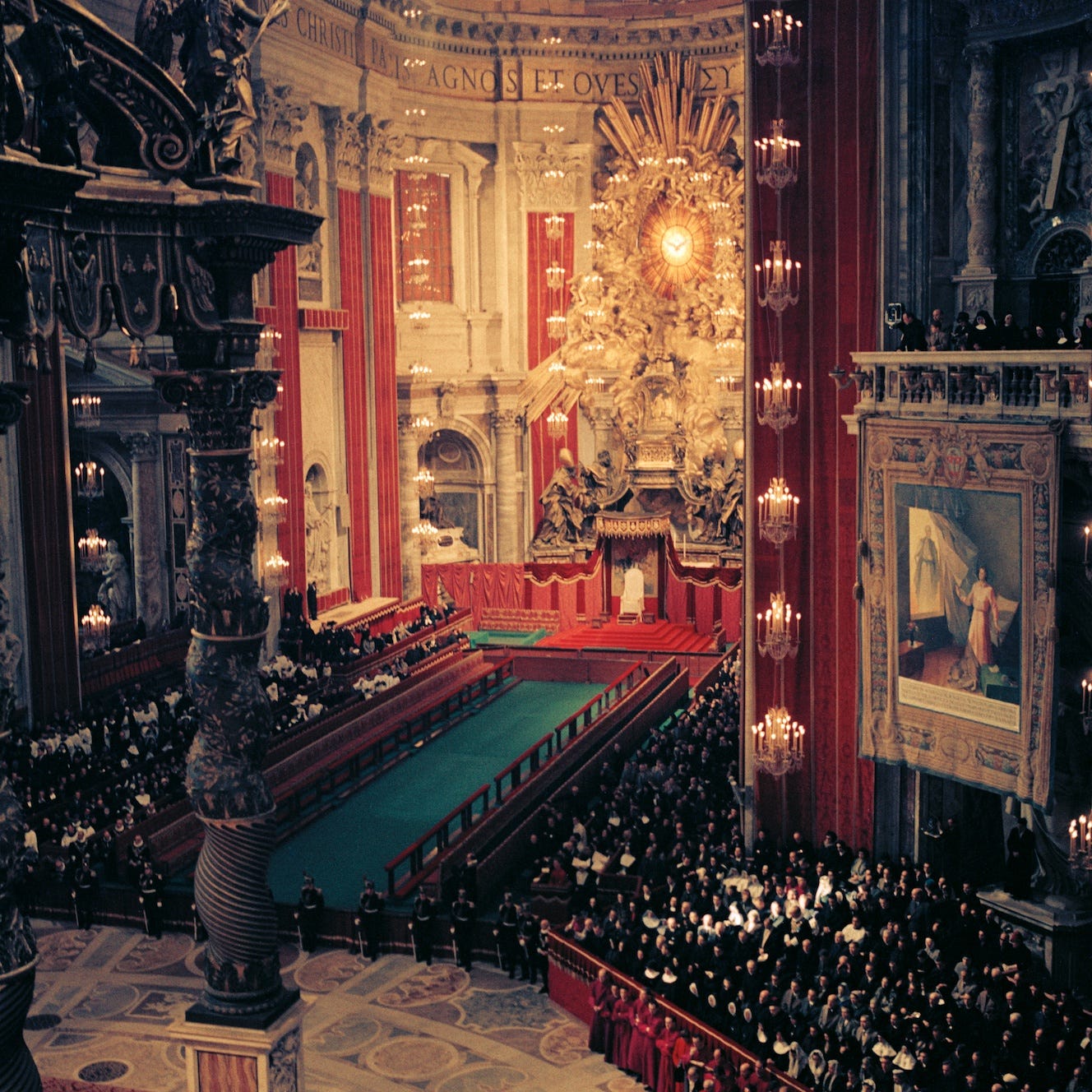

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, which most of us call Vatican II, opened 59 years ago Monday, on Oct. 11, 1962.

Don’t know much about Vatican II? Not sure why it matters? Here are some things to get you started:

What was Vatican II?

The Second Vatican Council was an ecumenical council: a meeting of the world’s bishops which “exercises power over the universal Church in a solemn manner.”

Since the fourth century of Christianity, ecumenical councils have been authoritative gatherings at which bishops discuss, debate, and discern how to teach the faith and define doctrine, how to correct error, and how the Church should be led.

There have been 21 ecumenical councils in the Church’s history, although most Orthodox Christians, among others, accept only the first seven as valid.

The Second Vatican Council lasted from October 1962 until December 1965. It was conducted in four sessions, one each year, which were attended by Catholic bishops from around the world, along with their theological advisors.

Before and between the sessions, drafting committees worked on a series of documents on the Church’s life, worship, and ministry, while seeking input and consultation from bishops around the world. Bishops debated and discussed those draft documents, called schemata, during the council sessions, ultimately voting on whether to approve them.

Altogether, more than 2,600 bishops from around the world attended the meetings.

What was it for?

Pope St. John XXIII announced the Second Vatican Council in 1959. He explained ahead of the council that he wanted it to be an opportunity for an “aggiornamento” — a serious reflection on how to express and live the truths of the faith in a way that would be heard, understood, and received in the Church’s contemporary context.

The council was not held to clarify particular doctrines or address specific theological problems. Instead, Pope St. John XXIII said he wanted the council to focus on the way in which the Gospel could be expressed most meaningfully and compellingly by the Church’s life and ministry.

When he opened the first session, John XXIII explained that “The greatest concern of the Ecumenical Council is that the sacred deposit of Christian doctrine should be more effectively defended and presented.”

“This teaching embraces the whole human person, body and soul, and it commands us pilgrims, who dwell on this earth, to strain eagerly towards the heavenly homeland… But for this teaching to reach the many fields of human activity which affect individuals, families, and social life, it is first of all necessary that the Church never turn her eyes from the sacred heritage of truth which she has received from those who went before; and at the same time she must also look at the present times which have introduced new conditions and new forms of life, and have opened new avenues for the Catholic apostolate.”

The pope said his hope for the council “is that the whole of Christian doctrine,

with no part of it lost, be received in our times by all with a new fervor, in serenity and peace.”

What did it do?

The Second Vatican Council produced several documents.

The four most important are called “constitutions.” They are:

Sacrosanctum concilium, the Constitution on Sacred Liturgy. This document aimed for a “restoration” of sacred liturgy, focused on the call of all Christians to participate with “full and active participation” in the Church’s liturgy, which it called “the summit toward which the activity of the Church is directed,” and “the font from which all her power flows.”

Lumen gentium, the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church. This document aimed to express the nature of the Church, which it described as the “People of God.”

It emphasized the “universal call to holiness” — the notion that all people are called to become saints — and it stressed the Church’s evangelical mission to proclaim, teach, and give witness to the Gospel. It also emphasized that Christ is the center of the Church, and that Christ’s messianic mission is expressed and lived by the Church.

Dei verbum, the Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation. The document emphasized that Christ is the “mediator and fullness of all revelation,” whose incarnation makes manifest “the deepest truth about God and the salvation of man.”

The document expressed that Christ is in the center of the story of salvation reveled in Scripture, which is received, handed on, and interpreted by the Church. Scripture should be read in harmony with the Church’s living Tradition, using the tools of scholarship in concert with the guidance of the magisterium, and, is meant to encountered, and understood, most especially through its context in the liturgy.

Gaudium et Spes, the Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World. The document expressed that in a changing world, the Church shares “the joys and hopes, the griefs and anxieties” of all people, and proposed that the Church is “a leaven and as a kind of soul for human society as it is to be renewed in Christ and transformed into God's family.”

The document emphasized that the Church can “shed light on the mystery of man and to cooperate in finding the solution to the outstanding problems of our time.” The council called for love, respect, and engagement with both believers and non-believers toward a more just and humane world, in which believes draw from the life of grace to engage with all people toward “the rightful betterment of this world.”

It stressed that “The Lord is the goal of human history, the focal point of the longings of history and of civilization, the center of the human race, the joy of every heart and the answer to all its yearnings.”

In addition to the four “constitutions,” the council produced documents on lay, priestly, religious, and episcopal vocations, religious freedom, missionary activity, ecumenism and inter-religious engagement, education, and communications.

Those documents, informed by the constitutions, aimed to emphasize the centrality of Christ in the Church’s life, the “universal call to holiness,” and the engagement of the Church in the modern world.

Why is Vatican II controversial? And what happened after?

After the council, the Church’s leaders around the world set to the task of adapting the Church’s life, liturgy, ministry, and worship to the emphases and approaches of the Second Vatican Council.

A new Code of Canon Law was produced, and a new Catechism of the Catholic Church. And a new Roman Missal — the text that instructs priests in the celebration of the Mass — was produced, which is probably the most well-known of the results of the Second Vatican Council.

The Church is still in the midst of that adaptation process, which is supposed to aim at integrating the documents and approaches of the Second Vatican Council into the ordinary life of the Church.

That process has not always gone smoothly, and has involved to serious disagreement about what the Second Vatican Council means, or how it relates to the teachings and life of the Church which came before it. Many of those debates have centered acutely around liturgy and worship, but they impact numerous other areas of the Church. Differing readings of the Second Vatican Council are often part of the backdrop and context among bishops in disagreement over contemporary pastoral issues.

It has been the project of the last three popes — Pope St. John Paul II, Pope Benedict XVI, and Pope Francis, to oversee, guide, and direct that implementation process. But assessing the success of that project depends largely on a person’s own experience, theological perspective, and the metrics of assessment they use.

Because the Second Vatican Council aimed to state in new ways much about the Church’s life and ministry, it seems helpful to remember that the Church thinks and acts in centuries. While the last five decades have involved debate and disagreement about what the Second Vatican Council means for the Church, the process of unpacking most ecumenical councils has taken more than one lifetime — and unpacking Vatican II may still have a long way to go.

In fact, if it’s any consolation, many theologians suggest the Church is still unpacking the implications and meaning of Vatican Council I, which concluded Oct. 20, 1870 — 151 years ago.

The biggest issues with Vatican II seem to have been church leaders and church scholars reading the Vatican II documents in the "spirit of the age" (which remember, was the '60s) rather than what the documents actually said.

For example, devotees of the traditional pre-Vatican II Mass will complain that the post-sVatican II liturgy went well beyond the directives of "Sacrosanctum concilium" which called for much more gradual reforms. I tend to think they have a point.

A confusing analysis. As I read the constitutional documents I could find nothing to take exception to but then "the devil is in the details" as always, is it not? What came after is more telling.

My reaction to the changes brought about in the name of Vatican II is that they seem to have been unnecessary. It addressed a problem some have described -convincingly- as nonexistent. However it seems to have provided an opportunity to 'modernize' (read secularize) the church. The year it ended,1965, ushered in the moral decay of the West especially of the USA. Moral decay of the most depraved sort became rampant reaching into the church itself. At this point we seem to actually be heading rapidly for the end of civilization itself.

Not an event to celebrate but to overcome.