What is the Council of Cardinals for, anymore?

The pope's Council of Cardinal's isn't what it used to be. But with an ageing membership and anemic agenda, what is it for?

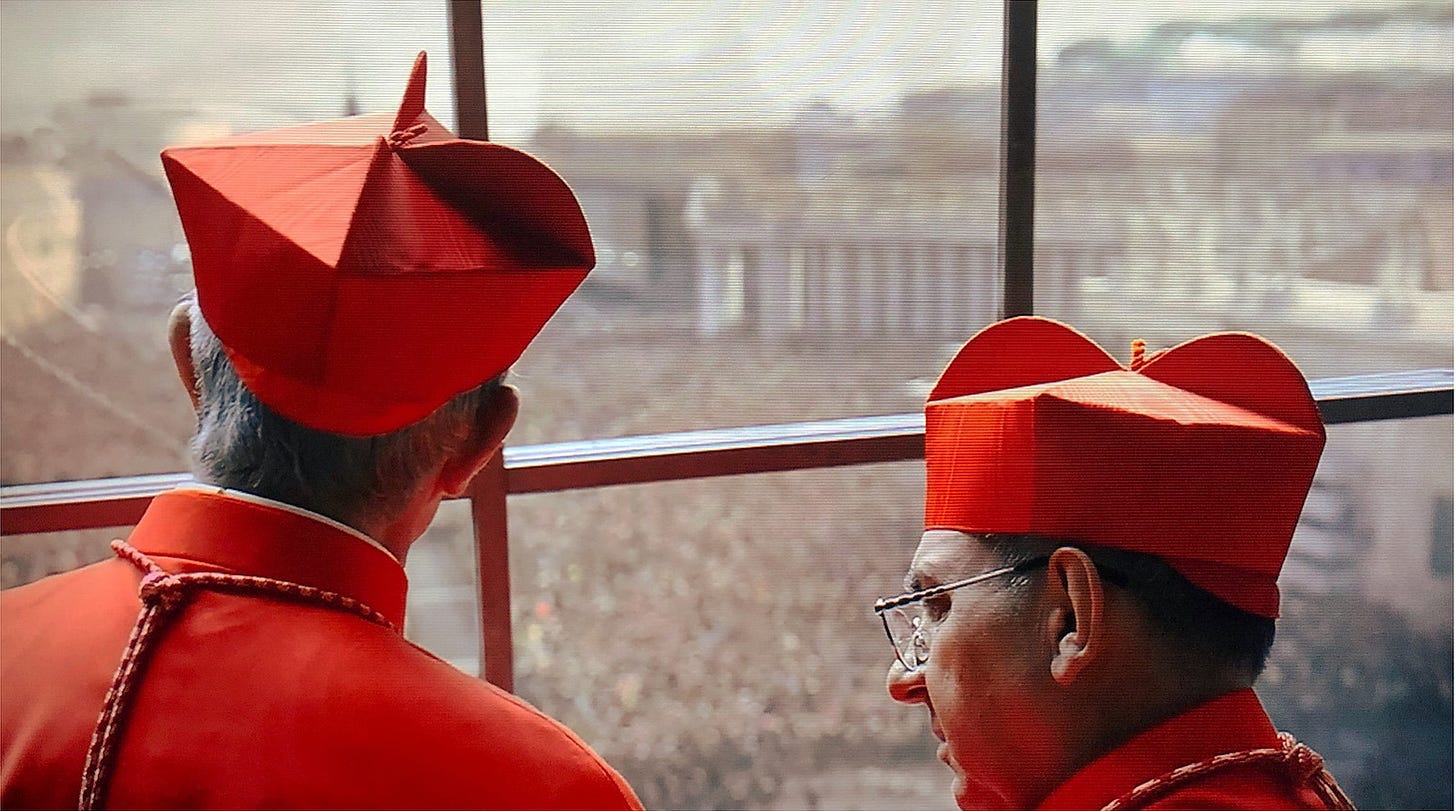

When the pope created the Council of Cardinal Advisors nearly a decade ago, its primary purpose was to advise Francis on the reform of the global governance of the Church, and to produce a new constitution for the Roman curia.

That document, Praedicate evangelium, was issued earlier this year.

With the council’s defining work accomplished, it has been depicted as something for a kitchen cabinet for the pope.

But the group’s ongoing agenda seems not to include most of the actually important issues facing the Church at a global level. And with several of the cardinal members approaching the age of 80 — and several dealing with scandals of one kind or another — the question now would seem to be: what, if anything, is the council for, anymore?

The answer may come when, and if, Francis chooses to refresh its lineup. In fact, a reset would probably reveal as much about how the pope sees his own future as it does about the future of his cardinal advisory body.

—

The Holy See press office on Wednesday issued a brief communiqué on the most recent meeting of the pope’s Council of Cardinal Advisors.

It explained that the cardinals met with Francis over two days this week to discuss several issues, including the U.N.’s climate change conference last month, the ongoing synod on synodality, the work of the Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors, and a recent meeting of the bishops’ conferences of Asia.

Those are, to be sure, interesting and important topics in their own right. But absent from the agenda, at least according to the Holy See press office’s account, were several items which many Catholics would have expected to see: among them Ukraine, China, and the Vatican’s financial trial

The pope himself has made it clear he views the war in Ukraine as probably the most important global event currently underway. Having previously identified Ukraine as the center of a slow-motion third world war, Francis this week compared Russian atrocities in the country to the Nazi campaign of WWII.

But those issues apparently did not merit input from the pope’s supposedly highest-level global advisory board.

Instead Secretary of State Cardinal Pietro Parolin and Congolese Cardinal Fridolin Ambongo Besungu were asked to present on the COP27 climate change talks in Egypt last month.

Parolin also was not called upon to brief the council on the progress of the recently renewed Vatican-China deal on the appointment of bishops. Given the recent move by the Chinese government to create a new diocese outside of the Church’s jurisdiction and draft in a serving Catholic bishop to serve as an auxiliary for it, one might otherwise have expected this to have been a key subject for the pope to seek counsel on.

And while the ongoing Vatican financial trial continues to make headlines — like a cardinal secretly recording the pope discussing state secrets — neither Parolin, Cardinal Giuseppe Bertello, the former head of the Vatican City State, were asked to comment on that.

Nor did the head of the Vatican’s Council for the Economy, Cardinal Reinhard Marx, address recent reports that his own council had circulated memos warning its reforms were in danger of becoming a “charade.”

Given that the Council of Cardinal’s original focus was meant to be on the reform of the Roman curia, one might have expected that financial affairs within the curia merited a conversation.

But in truth, the relatively anemic agenda of the council’s meeting would seem to suggest that either the council’s sessions - or perhaps the council itself - are increasingly irrelevant to the pope’s governance of the universal Church.

Even when highlighting purely regional issues, as the global group is also meant to do, the focus this week seems to have been on the banal, rather than the urgent:

The pope and other members of the council likely appreciated an update from Cardinal Oswald Gracias, the Archbishop of Bombay, on the October meeting of the bishops’ conferences of Asia.

But many might wonder if a more obvious topic for the council to discuss would have been the rolling crisis in India, where a series of bishops have been forced to resign - and another has had to seek police protection - in the wake of mass protests against liturgical reforms in the Syro-Malabar Church.

—

If Francis isn’t giving the Council of Cardinals many pressing topics to discuss, it’s just possible that part of the reason is the membership has become, at least in part, somewhat stale.

The council’s members, once called the C9 because of their number of, briefly renamed the C6, and now presumably dubbed the C7, are increasingly aged and, while geographically representative of the Church, not the formidable collection of key figures they once were.

More than half of its members - Cardinals Gracias, O’Malley, Maradiaga, and Bertello - have passed the ordinary episcopal retirement age, being 77, 78, 79, and 80 years old respectively.

Cardinal Bertello, while still a member of the Pontifical Commission for Vatican City State, is functionally retired, and was replaced as the head of the governorate last year. And while still nominally head of the Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors, Cardinal O’Malley has retreated from the role he once had as the face and voice of that body, ceding the spokesman role to Fr. Hans Zollner, SJ.

Other members of the pope’s supposedly highest-level council of advisors have had to contend with various scandals.

Cardinal Oscar Maradiaga, coordinator of the group, has for years faced allegations of serious financial misconduct in his home archdiocese of Tegucigalpa in Honduras, which led to an Apostolic visitation in 2017 but not to any clear resolution.

Cardinal Marx, meanwhile, has twice offered the pope his resignation as Archbishop of Münich (though not from his Vatican appointments) in response to the clerical abuse scandal in Germany. He is also the most senior bishop from that country, and a vocal defender of its controversial “synodal way” which was roundly denounced by senior Vatican cardinals during the German bishops’ ad limina visit just weeks ago.

Cardinal Parolin, Vatican Secretary of State, leads the most important curial dicastery in Rome and is probably the closest the council has to an ex officio member.

But pressing diplomatic issues in Ukraine and China to one side, Parolin’s department has been held up to widespread criticism, even ridicule, in the press as a Vatican court continues its vivisection of the secretariat’s financial scandal, laing bare what Vatican prosecutors see as a culture of mismanagement, fraud, corruption, extortion, and embezzlement.

📰

—

If the Council of Cardinals’ membership and deliberations appear increasingly marginal to the pope’s work governing the universal Church, it is worth asking what, if anything, he might choose to do to refresh the body.

An obvious and organic solution would be for Francis to usher in a turnover in its members, phasing out the superannuated members from around the world in favor of younger blood from his most recent crop of global appointments. The pope might at the same time ask Cardinal Besungu to take over the coordinating role, to bring a fresh perspective from the continent on which the Church is growing fastest.

The pontiff might also consider bringing in new Vatican blood, too. When the group met this week, they read a report on the synod on synodality prepared by Cardinal Mario Grech, who is overseeing the process ahead of its final sessions in Rome beginning next year.

Grech did not, it seems, attend the meeting, though he would appear to be an obvious candidate for membership if Francis wants the group to truly reflect what is foremost on the Church’s internal global agenda.

A second option for Francis would be to reimagine the council’s membership altogether, and opening it up to non-cardinals and even non-clerics.

It's ironic that the ad hoc group, created by Francis in the first place, should be entirely composed of cardinals, given that its major achievement was the promulgation of a new Vatican constitution paving the way for lay people to serve at the highest levels of the curia.

And the cardinalatial custom has created some notable gaps in the council’s ranks.

When the body was first created, a key member was Cardinal George Pell, Francis’ financial reform czar. Pell took a leave of absence from the body, and from his position as prefect of the Secretariat for the Economy, in 2017, before his terms on both bodies lapsed in 2019.

Since then, it would be an understatement to say financial reform has remained firmly on the Vatican agenda, but Pell’s successors as prefect of the financial secretariat were first a priest and then, most recently, a layman — neither of whom has been eligible to sit on the council as it currently exists.

—

Of course, Francis may elect to do nothing with the council, which could be a significant move in itself.

It’s clear enough that he doesn’t think its utility ceased entirely when the new apostolic constitution was promulgated, or he would have disbanded the body then, presumably with thanks for a job "well done."

But if the pope allows the membership to age out and shrink further, and for its meetings to drift into irrelevance, it could be a sign that the pope — who turns 86 in a few days time — isn’t looking far enough ahead to warrant rebooting the council.

It may be that, with the new constitution out and the synodal process locked in, Francis considers the big labors of his pontificate accomplished, and believes that what comes next is for someone else to decide.