Why the latest USCCB nominees lean in one direction

Is the future of Church politics mostly outside the episcopal conference?

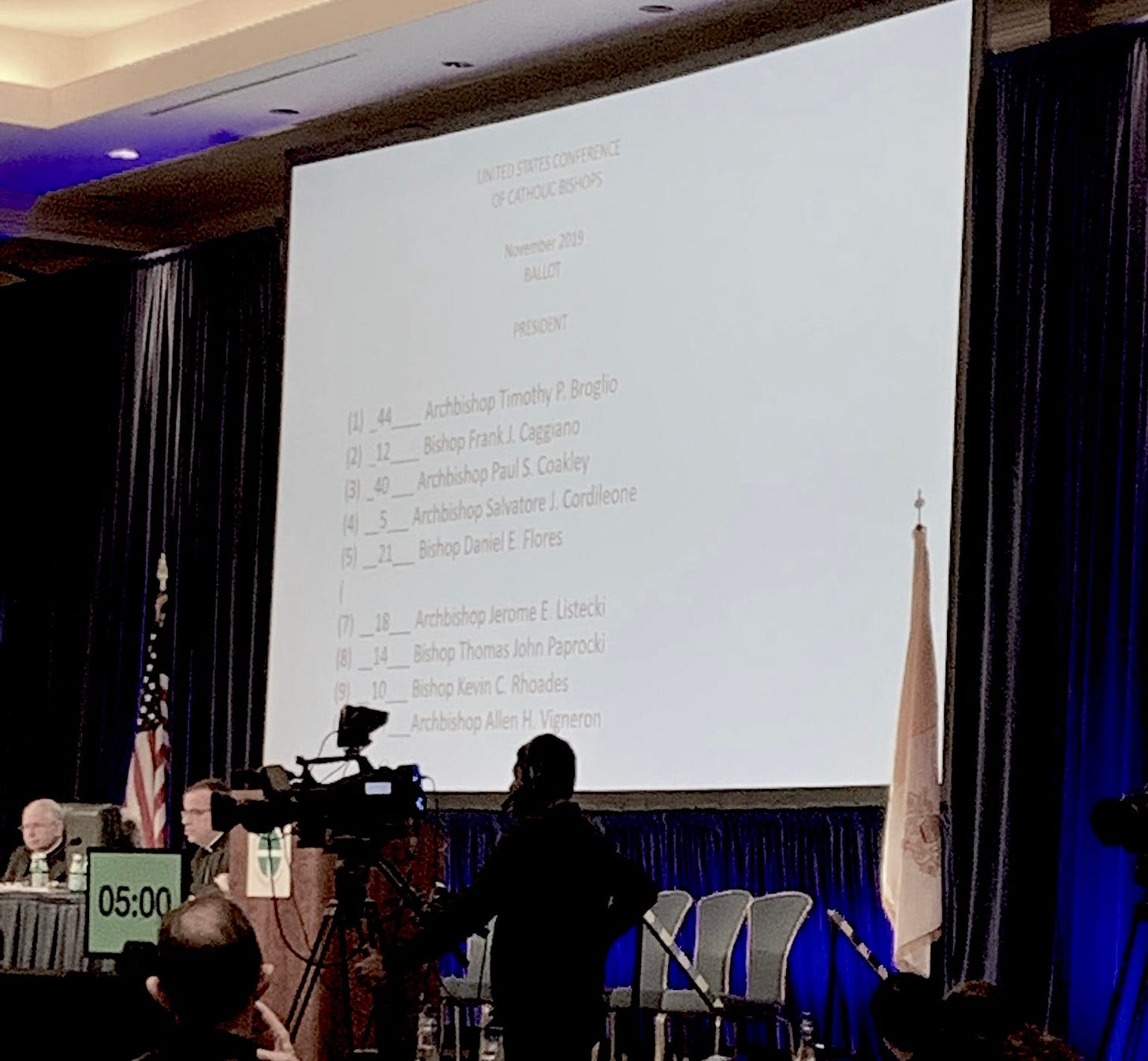

The U.S. bishops’ conference on Tuesday announced the candidates for the leadership of six standing committees, and for the officer position of secretary, to be voted upon at their November plenary meeting.

The conference has been roiled by serious debate in recent years — and more debates over politics, healthcare, and finances are coming.