Why Pope Francis never went home again

Pope Francis might go to Argentina in 2024. Here’s why it’s taken so long.

Before Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio boarded a flight from Buenos Aires to Rome in February 2013, he told the rector of his cathedral: “Nos vemos a la vuelta” — “see you around the corner.”

“Nos vemos a la vuelta” is a particularly Argentine way of saying, “see you soon” — not quite “goodbye;” much closer, perhaps, to “See you later, alligator.”

It seemed the right farewell as Bergoglio headed to a papal conclave, with the expectation that he would be back within weeks to his work as the Archbishop of Buenos Aires.

The College of Cardinals had other plans, electing Bergoglio to become the Bishop of Rome — and it’s been more than 10 years since Pope Francis has returned to his native Argentina.

But while the pope has, for years, demurred on the prospect of returning to his home country, now he has begun teasing the prospect.

In interviews this spring with Argentine media commemorating his 10-year pontificate, Pope Francis showed interest in returning to his native land in 2024, 11 years after he last packed up for a quick trip to Rome.

But it doesn’t seem by chance that Francis is telegraphing a visit for 2024. The pontiff has had for decades a complicated relationship with his country’s political class — and the prospect of a papal visit has always been likely to be politicized in Argentina, in ways that Francis would probably prefer to avoid.

But 2024 might just open a window which allows the pope to return.

Still, a decision is anything but certain. Even while he has shown interest in a 2024 trip, there are no concrete plans in place.

“There has been no contact with the episcopal conference about the visit,” a spokesman for the Argentine bishops’ conference told The Pillar.

“He has only expressed a deep desire to come to Argentina in 2024, but there is nothing planned that we know of,” the spokesperson said.

So, what’s so special about 2024, and why hasn't Pope Francis returned to Argentina already? When the answer involves Argentine politics, there is always a lot to unpack.

Peronism, Kirchnerism and dictatorships

For the last 80 years, Argentine politics has been dominated by three currents: Peronism, various military dictatorships and, more recently, Kirchnerism, a left-wing populist movement with Peronist roots.

Peronism in Argentina arose with the presidency of Juan Domingo Perón in 1946, an Argentine general who tried to establish a third way between Marxism and capitalism through a nationalist and populist movement.

"Peronism is a party of the masses. It is a party that was born under the protection of General Perón, with a right-wing ideology initially. But as a good party of the masses, his ideas could adapt. That’s how left-wing Peronism and right-wing Peronism ended up emerging,” explained Emilio Pintos, professor of Catholic social doctrine at the Argentine Catholic University.

“The three key ideas of Peronism are social justice, political sovereignty and economic independence. It is a nationalist movement that proposed, in the Cold War, a third way between the Marxism of Soviet communism and capitalism,” added Roberto Bosca, a lawyer and columnist on religious issues in several Argentina media outlets.

Perón repeatedly invoked the idea that his movement was inspired by Catholic social teaching, and he surrounded himself with Catholic intellectuals.

That framing “made many Catholics support Perón,” Bosca told The Pillar.

But “in 1954, the Church collaborated in Perón’s overthrow, because the emergence of Peronism was seen not only as an ideology, but as a political religion; the establishment of Perón as a messianic leader who proposes some truths that must be believed by all, the sacralization of the figure of his wife Evita as a saint, which aroused a religious devotion to the figure of Perón and his wife. This made the bishops and the Christian faithful in general withdraw from supporting the government,” Bosca added.

His government ousted in 1954, Perón would lead Argentina again in 1973, until his death in 1974. He was succeeded by his third wife and vice president, María Estela Martínez de Perón, until a military coup in 1976.

The military dictatorship in Argentina would last until 1981, but Peronism has continued as a force in the country's politics - even with a shifting economic strategy.

In the 1990s, Carlos Menem was the Peronist Argentine president who pushed for market privatization and “a more right-wing economic policy,” Emilio Pintos told The Pillar.

During the Menem government of the 1990s, Argentina entered a deep economic crisis: fallout from years of hyperinflation, a stagnant GDP, uncontrollable foreign debt, and increasing poverty.

So Peronism, always adaptable, adapted.

In the early 2000s, the Perónist governor of rural southern Argentine province of Santa Cruz — Néstor Kirchner — rode a wave of discontent, and won the 2003 presidential elections with a very different economic vision.

Kirchner led the country from 2003 until 2007. His wife, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, served eight years as president after him, and is now the country’s vice president.

Cardinal Bergoglio

As Archbishop of Buenos Aires and president of the Argentine episcopal conference between 2005 and 2011, Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio was the most visible face of the Catholic Church in Argentina.

But even in that role, he kept a low profile.

Today, it would seem strange to think that Pope Francis did not like to give interviews, but in his two decades as an Argentina bishop, he gave very few.

“We journalists who covered religious activity had the opportunity to see him at celebrations or in meetings—there he did have a formal dialogue with the press, but he didn't really like speaking or giving his opinion on current issues to members of the media,” Mariano de Vedia, author of the biography “Francis: The People's Pope,” told The Pillar.

But while he was archbishop of Buenos Aires, Bergoglio’s concern for the poor found him speaking out.

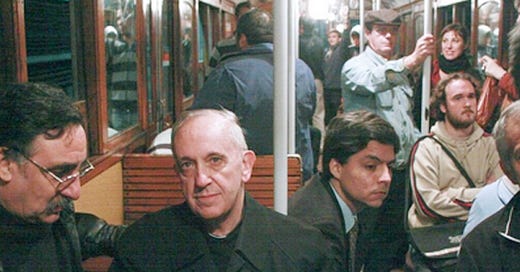

“He was always a very austere person, he did not accept living in the archbishop's residence on the outskirts of Buenos Aires. It's not a very luxurious house, but it has more comforts than the Buenos Aires curia, where some already-retired priests also lived, and he lived in a room in the curia and he was a bishop who visited the parishes a lot, in particular the villas”, said de Vedia, referring to the poorest areas of Buenos Aires.

In turn, Bergoglio promoted a movement of curas villeros, villa priests, who lived in parishes in the most vulnerable areas of the city—alongside the poor.

“I have a brother who is a cura villero, in the town of Barracas in the capital and he told me that the archbishop would go there without warning to take some mate, or that he went to the villas to officiate baptisms or confirmations, and he that habit of touring the parishes of the villas,” de Vedia added.

On those visits to the villas, Bergoglio noted the crushing poverty in which many Argentines found themselves. The experience of that poverty led the often-media-shy Bergoglio to get politically active — and eventually to a direct confrontation with the Kirchner government.

“An increasingly intense confrontation was forged based on the descriptions that he made of the social situation of poverty and unemployment in Argentina,” de Vedia said.

Archbishop Bergoglio began criticizing the government of Néstor Kirchner.

As early as May 2004, Bergoglio in a homily criticized the Kirchner government's “exhibitionism and strident announcements” and its intolerance of the opposition.

Kirchner pushed back.

“Néstor Kirchner was not a man known to be tolerant of dissident voices. This creates a very conflictive relationship between his government and Bergoglio,” said Pintos.

Kirchner even went so far as to call Bergoglio “the spiritual head of the political opposition.”

And indeed, Bergoglio supported other clerics who criticized the Kirchner government, and its Peronist allies.

“The governor of the province of Misiones, who was a Peronist, wanted to change the state constitution to allow the indefinite reelection of the governor through a referendum. There, Bishop Piña, also a Jesuit, with the support of Bergoglio, vehemently opposed it and the governor lost the referendum,” Pintos told The Pillar.

As tension escalated, Kirchner in 2005 decided not to participate in the Te Deum liturgy, customarily celebrated in the cathedral of Buenos Aires on May 25, Argentine independence day.

It was highly unusual for an Argentine president to skip the independence day liturgy.

“Kirchner wanted to avoid the possibility of Bergoglio giving a homily with critical content,” Pintos said.

But when Kirchner said he wouldn’t attend, Bergoglio canceled the Te Deum liturgy, and criticized the "partisanship" of the Kirchners.

In the ensuing years, Bergoglio remained a critic of the Kirchners.

In 2009, the cardinal would pronounce one of his strongest criticisms against the government, by then led by Cristina Fernández, Néstor Kirchner’s wife.

In response to media reports accusing the Kirchners of corruption, Bergoglio said that in Argentina, “human rights are not only violated by terrorism, repression, and murder but also by the existence of conditions of extreme poverty and unjust economic conditions that cause great inequality.”

The remark was taken as a direct rebuke of the Kirchners’ economic plan. And tension between the government and the future pope did not end there.

In fact, the pope believes that in 2010, he faced a politically motivated trial in the country.

In that year, Cardinal Bergoglio was called to testify about allegations that he had colluded with the country’s military dictatorship decades prior, and that he had in 1976 helped hand over two Jesuits who were tortured by the military during Argentina’s “Dirty War.”

The pope recently explained his testimony, revealing to Jesuits in Hungary this month that the government of Cristina Kirchner pressured the judges to have him sentenced for crimes against humanity.

“They wanted to cut off my head," he said in the meeting with the Jesuits, adding that, years later, one of the judges in the case “came [to the Vatican when Francis was pope] and told me clearly that they had received instructions from the government to condemn me.”

Bergoglio was not convicted of collusion, but the charge against him was — to him — a sign of the government’s opposition to his voice in the country.

In the same year, 2010, the Argentinian government came out in support of legalizing gay marriage, and moved towards passing a law to that effect.

A week before the approval of same-sex marriage, Bergoglio released a pastoral letter, in which he rebuked the prospect of gay marriage in unsparing terms.

“Here too is the envy of the Devil, through which sin entered the world, which cunningly seeks to destroy the image of God: man and woman who receive the mandate to grow, multiply and dominate the earth (...) Let's not be naive: it is not a simple political fight; it is the destructive claim to God's plan. It is not a mere legislative project (this is only the instrument) but a 'movement' of the father of lies that seeks to confuse and deceive the children of God.”

The cardinal’s letter came even as Bergoglio had privately expressed among bishops his openness to supporting a compromise, which might support same-sex civil unions, but not marriage itself.

But when the bishops decided to push back against the government, Bergoglio took up the cause.

“Within the episcopate there was a discussion about what strategy to present in the face of the debate and there were two positions: some argued that the Church had to agree with the government on the approval of an intermediate plan, such as that of the civil union, but in the episcopate prevailed the position of absolutely rejecting any change in the marriage regime,” de Vedia said.

“So Bergoglio submitted to that majority and publicly condemned and rejected the approval of the homosexual marriage law. And many Kirchnerist representatives and senators concentrated on Bergoglio’s voice in the debate,” he added.

"That further broke the cardinal's relationship with Kirchnerism."

The legalization of gay marriage in Argentina would also lead Cardinal Bergoglio to clash with the mayor of Buenos Aires, Mauricio Macri, who would later be president of Argentina between 2015 and 2019.

Macri, not a Peronist, supported the legalization of same-sex marriage. Bergoglio criticized him for that, and the rancor saw Macri decline to attend the Te Deum at the Buenos Aires cathedral in 2011.

Bergoglio would later criticize him for his “delusions of grandeur.”

It might seem strange today, but that confrontation left Bergoglio painted in the Argentine press as a staunch conservative.

“Bergoglio is a Jesuit and constitutionally a Jesuit has a hard time being conservative,” Pintos said with a laugh. “I'm not saying that as a good or bad thing, but it's reality.”

The choice

On March 13, 2013, the white smoke announced a new pope — Jorge Bergoglio had become the first South American pope in history, and obviously the first Argentine.

The reaction of Cristina Kirchner’s government in Argentina was lukewarm.

"For the first time in the 2,000 years of the Church's history, there will be a pope who belongs to Latin America and we sincerely wish that Francis can achieve a greater degree of brotherhood among peoples, among religions," President Cristina Kirchner said cooly in a statement, while many of her supporters took to the press to lambast their compatriot, the newly elected pope.

“The president did not even mention Bergoglio by name or say that he was Argentine, nothing. And that generated a general whistle from the militants,” Pintos told The Pillar.

In fact, Kirchner had almost spoken more critically of the new pope — until she was reportedly convinced it wasn’t a fight worth picking.

“When Cristina Kirchner was told of Bergoglio's election, she took it very badly. But when Cristina was receiving calls and congratulations from the neighboring presidents, the president of Ecuador, Rafael Correa, a man from the left allied with the Kirchners, made her see that it was not convenient for her to confront the pope,” de Vedia said.

“Then, Cristina made a turn, and summoned some Peronists who had links with the Church, and managed to make the trip to go to the papal inauguration.

In addition, she had an hour-long audience with newly elected Pope Francis, in which a kind of rapprochement apparently took place. After that there were gestures from Cristina of enthusiasm for having an Argentine pope — and from there, relations improved, at least at a discursive level," de Vedia added.

“The emphasis that Pope Francis placed on the preferential option for the poor was an important point, which in a certain way linked him with Peronism because Peronism has a very important emphasis on social justice,” Bosca told The Pillar.

“Francis also received several Peronist leaders in the Vatican, which caused a true political instrumentalization of those visits, with people saying that the pope was a Peronist,” added Bosca.

"I was never affiliated with the Peronist party, I was not even a militant or sympathizer of Peronism. Saying that is a lie," Francis said in an interview for the forthcoming book “The Shepherd.”

In another interview, the pontiff complained about politicians who politicized their meetings with the pope, in a move taken as a clear nod to the Peronist militants.

“I received and receive everyone. But sometimes there are some who seek to obtain political gain, not always very artfully, even.”

“The case of a candidate who attended Mass in Santa Marta comes to mind. At the end he asked me if he could take a picture with me, I said yes and asked him not to do any mischief. He replied that the photo was to be shared with the family, but the following week, Buenos Aires was covered with campaign posters of his photo. That kind of thing should not be done,” added the pope.

‘The Crack’

Polarization in Argentina, between a largely Peronist working class and a profoundly anti-Peronist middle and upper class, between businessmen tired of bureaucratic obstacles and economic crises and all-powerful unions, between conservatives and progressives, is so deep in Argentina that the famous journalist Jorge Lanata gave it a name: “La grieta” — “The Crack.”

In Argentina, there is no need to explain further. Everyone seems to know what The Crack means in the country.

And it’s possible that The Crack has kept the pope out of Argentina.

“Cristina Fernández managed to improve the relationship with the Vatican but the pope never lost sight of the fact that a visit was not convenient in the context of The Crack. I believe that the pope did not want to be hostage to any political organization that could say: ‘We brought the pope!’” added Pintos.

“Francis did not come in the last two years of Cristina Kirchner's term because the social crisis worsened and poverty increased,” de Vedia said.

“Cristina visited the pope in Rome twice between 2013 and 2015. She also visited him when the pope was in Cuba and in Brazil, but when she went to Brazil she did not have a private audience with Francis,” added de Vedia.

“When the pope went to the 2013 World Youth Day in Rio de Janeiro, Cristina appeared there and tried to see the pope, but the pope did not receive her. Still, in all the media, it appeared that she was there with the pope. It was real harassment,” Bosca said.

“She only participated in a ceremony with her then main candidate for the House of Representatives, Martín Insaurralde. She was looking for a photo of her candidate greeting the pope, but later that didn’t serve her much, because the candidate lost,” de Vedia added.

In 2015, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner left power in Argentina.

Mauricio Macri, the center-right non-Peronist former mayor of Buenos Aires, with whom Bergoglio had clashed over his support for gay marriage, was elected president.

“With Macri there was never a very fluid relationship. Macri went to visit the pope in Rome a few months after he assumed the presidency and the audience lasted exactly 22 minutes and there was an image in which the pope appeared very circumspect, very dour,” de Vedia.

Of course, it could be said that the image was taken at the wrong time, or that it is too speculative to draw conclusions from a photo, but in Argentina many came to a definite conclusion — many Catholics decided that the pope did not have a good relationship with President Macri.

In a recent interview, Pope Francis said that he had tried to plan a 2017 trip to Argentina, Chile and Uruguay, but a scheduling problem prevented him from traveling at the desired time.

The scheduling problem seems plausible — In Chile there were presidential elections and the pope wanted to avoid politicizing his trip. Because of the election, it was only possible to go to South America in January, when the vast majority of Argentines go on vacation and Buenos Aires is deserted. Hardly the best setting for a papal visit.

Although the relationship with Macri was never close, it had been at least cordial. But facing pressure from members of his own coalition and also from sectors of Peronism, Macri, who is pro-life and vetoed a law that would legalize abortion in Buenos Aires during his time as mayor, opened a national debate on abortion in the country.

“That broke Francis’ relationship with Macri, even though the Senate refused to legalize abortion by very few votes. It was seen as an attempt to distract public opinion from the terrible economic crisis the country was experiencing,” de Vedia said.

The pope was very critical of the Macri government. That and his reconciliation with Cristina Fernández de Kirchner earned him the rejection of a sector of the Argentine population.

“The pope has a distrust of Macrismo because he saw it as the government of the CEOs, of the technocrats and he strongly criticized this, which provokes the anger of the anti-Peronist middle class,” said Bosca.

“Macri did not have many people around him worried about strengthening the bond with the pope. In that, the most clever Kirchernerists always have congress members or officials who already have a good bond, or because they emphasize the issue of social concern, then this brings them closer to the Church,” de Vedia added.

In 2019, a Peronist was elected again, Alberto Fernández, who appointed an old acquaintance as vice president: Cristina Fernández de Kirchner.

Fernández took pains to visit Francis after his inauguration as president.

But the president’s support for abortion, and clashes over the International Monetary Fund, saw his relationship with pope cool quickly. Francis has become critical of Fernández’ approach to poverty in Argentina.

Their cool relationship meant that while presidential administrations in Argentina have come and gone since Francis was elected pope, none have had a close relationship with the pope.

“The Gospel says that no one is a prophet in their land and I think that happens a little bit like that,” Pintos said, adding that the country carefully scrutinizes Francis for a sense of his political opinions about domestic affairs.

“In Argentina, we were all very aware of whether Francis smiled more at one person than at another,” Pintos added.

Bosca and other analysts put it directly: If the pope goes to Argentina, he’ll fall into The Crack.

“I think he wants to keep his distance from the perception that arose in Argentina that he is politically linked with Peronism and the left, which is a fairly widespread belief in the middle and upper class. Resistance has grown among this sector of society because there is a deep anti-Peronism in them and, seeing the pope apparently involved with Peronism, he falls into the same bag,” said Bosca.

“Unlike other Latin American countries, in Argentina there is a very important and deep-rooted historical middle class that has been politically decisive and that, although it has been greatly flattened in recent years due to the [economic] crisis, continues to maintain a cultural and political dominance as well,” he added.

For their part, politicians in Argentina have taken pains to tell the pope that if he comes, they’ll help him overcome The Crack.

In fact, politicians from the ruling party and its opposition, who don't even speak to each other in their daily lives, have signed a joint letter promising that the visit will not be politicized.

But given the history, and the breadth of that crack, the pope might not be certain.

The possible trip

But even while politics remain sharp in Argentina, the pope has expressed openness to a 2024 trip. Bosca said that’s a sign of cooling political tension in the country.

“The situation for the pope in Argentina — he faces nearly political harassment — makes him uncomfortable and has produced a reluctance to come to Argentina,” said Bosca.

“But in recent times the climate has changed and there is no longer such a strong opposition [to Francis], which may cause a certain relaxation for the pope to travel to Argentina.”

And it does not seem to be a matter of chance that Francis has recently expressed his desire to go to Argentina. The timing fits into the political cycle.

There will be a presidential election in the country at the end of 2023, but the presidential campaigning has not yet started, and the candidate field is wide open.

The country’s current president, Alberto Fernández, recently announced he would not run for re-election, which means the government still does not have a candidate.

The primary of the main opposition coalition, which elected Macri in 2015, is still an open race.

So when the pope said he was open to going in 2024, he did so in a way that avoided the appearance of supporting any candidate, and an openness to visiting regardless of who wins.

“Francis is saying: I'm going in 2024 no matter who wins,” explained Pintos.

Succession

But politics aside, there is another factor in play, which might be the last of a puzzle, as Francis sets a date for a possible return to Argentina: the appointment of the next archbishop of Buenos Aires.

“The current archbishop, Cardinal Poli, who was appointed in 2013 by Francis in one of his first appointments as pope, turned 75 in November of last year and resigned, so it is expected the pope will soon decide who will be his successor,” de Vedia said.

“Perhaps that is also a factor that is at stake when setting the trip to Argentina.”

And if the visit takes place, Francis will have to face a growing problem in Argentina: the rapid secularization underway across the country.

“People claim to be Catholic, but they don't approach the sacraments, they don't commit themselves,” said Emilio Pintos.

“The vocational crises that exist are really gigantic, there are huge schools, run by religious institutes which no longer have brothers, or which have two or three priests in a school for 1,000 students. When I studied in one of these schools, half or more of the teachers were religious,” he added.

“The number of seminarians has been greatly reduced, there were times when in the Archdiocese of Buenos Aires between 20 and 25 priests were ordained per year and years in which more than 30 were ordained, and today four or five are ordained at the most in Buenos Aires, which is the largest diocese in the country,” de Vedia said.

It is unlikely that a papal visit could, by itself, solve that problem — but it might help. Bishops in Argentina have certainly told the pope they think his presence could make a difference.

But the politics don’t make it easy. And while there seems to be a window in 2024, and Pope Francis says a visit could be “just around the corner,” Argentines might still find themselves waiting for their native pope to come home.

Editor’s note: This analysis initially identified the Menem presidency as a period of hyperinflation, which was inaccurate. Instead, Menem’s administration was preceded by a period of serious inflation in Argentina. The analysis has been corrected.

This was an informative deep-dive into something I knew nothing about. Thank you, Edgar!

Very informative article, thank you. I can't help but wondering if the Church (and Cardinal Bergoglio in particular) had always emphasised Christ crucified and the salvific mission of the Church, that he would be less likely to be used by any party. Pope John Paul II (both while cardinal in Poland and as pope) stayed pretty much on message, and traveled to the most hostile places to evangelise. It seems that Jesus alone can straddle the Crack (since both lower and middle classes claim for the most part to be Catholic).

I confess that I have no access to his homilies while he lived there, but the significant decline in vocations indicates that the local church may have lost its way.