When Archbishop Rui Valério is installed Saturday as the new Archbishop of Lisbon, he’ll also get a very cool title — he will be known from then on as Rui I, the 18th Patriarch of Lisbon.

Valério — who was ordained as a Monfortine Missionary and previously served as bishop of Portugal’s military ordinariate — was selected by Pope Francis on Aug. 10 to take on the new role.

What exactly is a patriarchate? And how did Lisbon become one?

You have questions, and The Pillar has answers:

What is a Patriarchate?

Historically there were five patriarchates – collectively known as the Pentarchy – in the early Church. These were, essentially, the five main dioceses in the early Church, founded by apostles and simultaneously centers from which the faith was spread.

The original patriarchates were Rome, Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem. Constantinople was added later, essentially due to its importance in the Roman empire, and linked to St Andrew.

Traditionally, the leader of each one of these dioceses was styled a patriarch. While there was supposed to be only one for each, historical divisions have led to many of them having multiple patriarchs. For example, there are five Patriarchs of Antioch (three Eastern Catholic, one oriental Orthodox, and one Eastern Orthodox). The Coptic Orthodox Pope, currently Tawadros II, is Patriarch of Alexandria, but so is the Coptic Catholic Patriarch, and the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Alexandria.

Constantinople and Rome continue to have only one leader: the Orthodox Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew in Constantinople, and Pope Francis in Rome.

So then, Pope Francis is a patriarch?

Well, yes, but also no.

Yes, because as bishop of one of the ancient patriarchates – in fact the first and foremost of the ancient patriarchates in terms of primacy (what exactly that means is a matter of dispute among Catholics and Orthodox) – Francis is ipso facto a patriarch.

In fact, for many centuries, one of the official titles of the pope was Patriarch of the West.

Msgr. Michael Magee of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia knows the subject well. He defended the importance of the title “Patriarch of the West” in his doctoral dissertation, entitled “The Patriarchal Institution in the Catholic Church.”

But just as Magee was finishing up his work on the dissertation in 2006, he learned that Pope Benedict had decided to drop the title.

“In my dissertation I had emphasized the importance of the pope's patriarchal role in the Latin Church, and indeed, as the only ecclesial figure exercising such a role within the Latin Church,” Magee told The Pillar.

“And just before my defense, I learned from a friend who had it by word-of-mouth from a source close to Pope Benedict that the title was about to be renounced publicly.”

He was shocked by the news.

“The title vividly expressed the role that the pope shares with the Eastern Patriarchs, each acting with their synods as stewards of distinct ecclesial traditions,” he said.

“That recognition, of course, in no way should be understood to obscure the universal primacy that the pope alone exercises, any more than his role as Bishop of Rome does. He is a bishop while being more than simply one of the others, and he is a patriarch too, while being more than simply one of them.”

So there are five patriarchates total?

Originally, yes. But now, not so much. Because of the Church’s complicated history.

In the Orthodox Christian world, and even before the great schism of 1054 (which saw the Byzantine Christian churches, centered around Constantinople, split from Rome, forming what are now known as the Eastern Orthodox and the Latin Catholic churches) the tradition arose of forming churches based on ethnic or linguistic groups which were self-governing, or autocephalous, but in communion with each other.

The leaders of many of these churches also became known as patriarchs. Thus, the churches of Russia, Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria and Georgia all have patriarchs, as does Constantinople, among others.

Sometimes a patriarch goes by a different name, but the essence is the same. Therefore, Rome and Alexandria have popes, and the Armenians and Malankara Orthodox have Catholicos.

But there are also Catholic patriarchs, right?

Right.

As many Eastern Orthodox communities chose to return to communion with Rome, they continued to organize according to the Eastern tradition of ethno-linguistic groups, and to use the titles proper to their tradition.

Not all heads of Eastern Catholic churches are officially known as patriarch, but six are: namely those of the Maronite Church, the Melkite Church, the Coptic Catholic Church, the Syriac Catholic Church, the Armenian Catholic Church, and the Chaldean Catholic Church.

Many Ukrainian Greek-Catholics have claimed that their leader should be styled a patriarch, a move that Rome has resisted, for ecumenical reasons — largely so as not to offend the Russian Orthodox.

The important thing to note is that as leaders of Eastern Catholic Churches, which are known canonically as sui iuris churches, these patriarchs hold much more authority than ordinary diocesan bishops. They are elected by their own synods, and not designated by the pope, and they govern their churches with some degree of autonomy from Rome.

But then there is another kind of patriarch — the Latin Patriarchs, in Jerusalem, Venice, Lisbon, East Indies and West Indies.

Wait, what’s a Latin Patriarchate?

Although there are some differences among the five Latin Patriarchates, they are functionally normal archdioceses which have had an honorary title bestowed upon them. Their bishops do not share the same authority as Eastern Catholic patriarchs, and are therefore often referred to as titular or honorary patriarchs.

Still, there are some differences among them. The Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem stands out, since it is a remnant of the crusades and the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, during which the Europeans wished to replace the Eastern patriarch with one of their own.

So although the Latin patriarch, currently Archbishop Pierbattista Pizzaballa, does not have the same authority as an Eastern patriarch, his title comes from the Church’s most early patriarchates.

Venice is also a unique case, since the title was actually inherited from the early Patriarchate of Aquileia, on the Mediterranean, which was on the border of the Eastern and Western Christian worlds. As the religious geography changed, Venice engulfed Aquileia, which ceased to exist, but the honor of the patriarchate was maintained.

The patriarchates of the East and West Indies were essentially Roman outposts in the New World. For centuries, the Patriarch of the East Indies had real authority over other Catholic dioceses on the Indian subcontinent, and all the way to Macau. As communication with Rome became easier and European colonialism began to recede, the authority was dropped, but the current Archbishop of Goa retains the honorary title.

The Patriarchate of the West Indies has been vacant for around 60 years, though not officially abolished.

And then there is the Patriarchate of Lisbon, which is another case altogether, unique in itself.

So why is Lisbon a patriarchate?

The easiest answer is that Lisbon became a patriarchate in the 18th century, largely because of the vision and unbridled ambition of one man: King John V of Portugal.

Finding himself the master of large parts of Africa, Asia, and South America, and with his treasury bursting with Brazilian gold, he began to see himself as the lord of a new Christian empire, rivaling the Holy Roman Emperors themselves.

King John V knew that his legitimacy depended on the blessing of the pope, so he sent an extravagant embassy to Rome, hoping to convince Clement XI to grant Lisbon special honors, including the rank of patriarchate.

What really convinced the pope was King John’s willingness to send an armada to defend Venice from an Ottoman fleet. The pope had asked various Catholic kings for help, but only Portugal answered the call.

“This was largely a case of affirmation of the Portuguese empire among other European courts,” said Fr. Bruno Machado, a Lisbon priest who is director of the Cultural Centre of the Patriarchate of Lisbon.

“He needed the pope to legitimize his pretension to being the king of a large empire, and the pope granted it to him in 1716, creating a sort of miniature Rome in Lisbon.”

Initially, the title of patriarch was not attributed to the Archbishop of Lisbon, but to the King’s royal chaplain. Because of this, the archdiocese split into two: Eastern Lisbon, which remained under the archbishop, and Western Lisbon, which became the patriarchate. Later the two were merged again.

The pope’s decision to raise Portugal’s royal chaplain to the rank of patriarch can thus be seen through two lenses. It could be viewed as a sign of gratitude on the part of the pope for Portugal’s assistance in a time of need, as well as a recognition of Lisbon’s role – similar to what took place with the earlier patriarchates – in spreading the faith to other parts of the world. Or it could be viewed as a privilege bought at tremendous expense by an ambitious monarch. In reality, there is probably truth to both views.

Did he say a miniature Rome in Lisbon? Come again?

One of the unique characteristics of the Patriarchate of Lisbon is the number of privileges given to it, which had previously been reserved to the pope.

Among others, the Patriarch of Lisbon was allowed to use a variety of liturgical items and vestments that only the pope could use, such as flabels, falda and fanon.

The Patriarch of Lisbon was also the only cleric besides the pope himself who could be carried in a gestatorial chair, although his was carried by eight men, rather than 12. All of those traditions have fallen into disuse both in Rome and in Lisbon.

The patriarch was also granted the privilege of using a cardinal’s garments before being elevated to the cardinalate, which according to a papal bull should take place in the first consistory after he is nominated.

This latter privilege, though not officially abrogated, was tested during the term of the previous patriarch, Manuel Clemente, who became patriarch when his predecessor, José Policarpo was still a cardinal of voting age. Policarpo then died unexpectedly and Clemente was elevated to the College of Cardinals in the next consistory.

Rui Valério was nominated after the list of cardinals to be raised in September had been published, but it remains to be seen if he will be made a cardinal before Clemente turns 80, or if he will have to wait five years for Clemente to age out of voting.

Is there anything else unique about Lisbon?

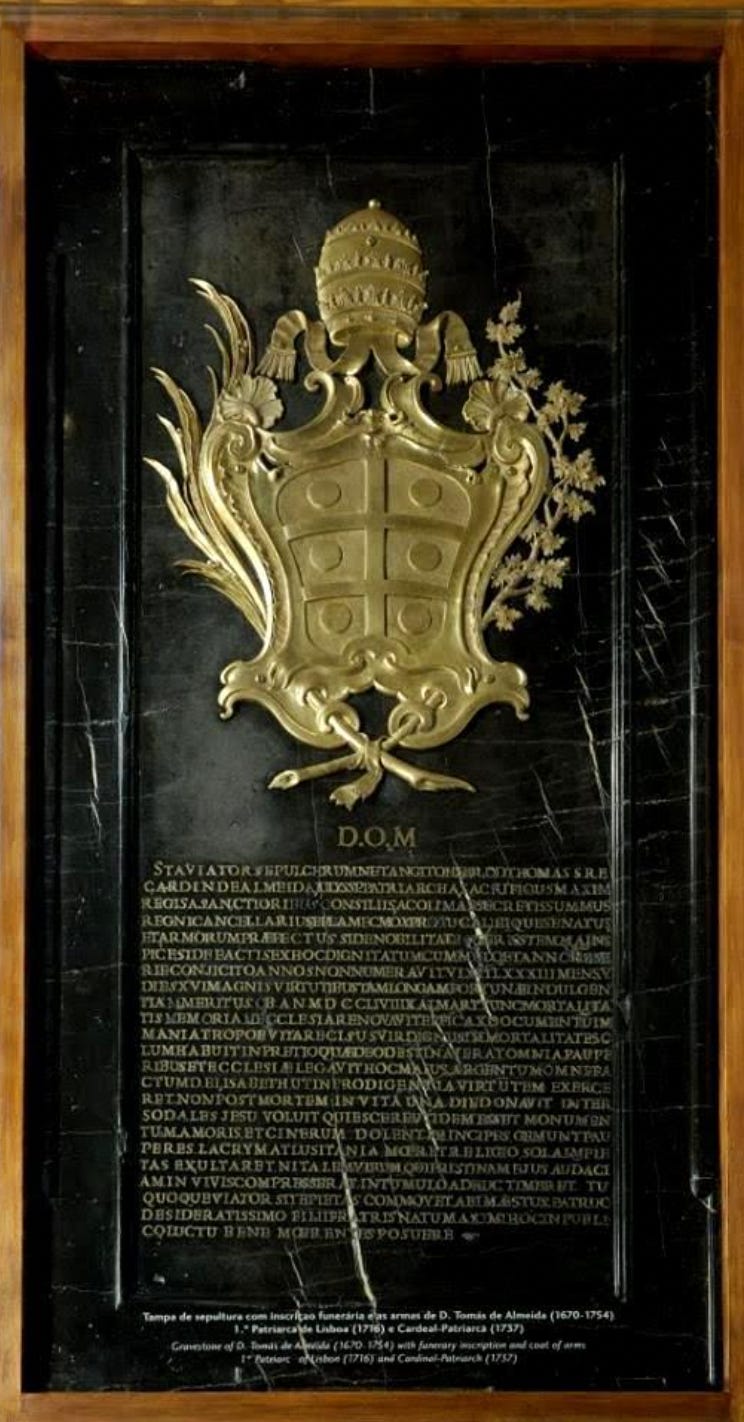

One of the most remarkable privileges of the Patriarchate of Lisbon is the use in ecclesiastical heraldry of a triple tiara, or triregnum, almost identical to that which was traditionally worn by the pope.

The only difference is that while the papal tiara is adorned with the crossed keys of St Peter, the patriarchal tiara of Lisbon has the archepiscopal double cross, and a bishop’s staff.

The tiara still tops the official coat of arms of the patriarchate, and of the patriarch himself.

But its history is not exactly straightforward.

“The tiara itself never existed,” historian and expert in heraldry Lourenço Correia de Matos told The Pillar.

Furthermore, he said, “there is actually no record of the pope attributing this privilege to the Patriarch of Lisbon. It seems to have been a cheeky overstep on the part of the Portuguese, but the fact is that the tomb of the first patriarch already featured a triple tiara, and Rome never objected to its use, so one can say that it has been legitimated over time.”

But while there is no actual tiare, Lisbon’s patriarchs have used a special three-tiered miter, however, with each tier containing precious stones, intended to symbolize the tiara.

Is there a future for the Latin patriarchates, and for the Patriarchate of Lisbon in particular? At a time when even the papacy has been doing away with external symbols of pomp and circumstance, would it not make sense just to stop using these titles?

Views on the issue differ.

Msgr. Magee is of the opinion that the Latin patriarchates should be a thing of the past.

“The use of the title honorifically is a vestige of a medieval Latin distortion of the term that reached its apex when the Sees of Antioch and Constantinople were temporarily occupied militarily by Western Christians, and their venerable patriarchal thrones occupied by Latin bishops imposed from outside upon the Eastern Christians there,” he said.

“Certainly, different ecclesial traditions are entitled to use the same words in different ways as one aspect of their legitimate diversity, but I have always thought that a renunciation of the merely honorific patriarchal title by Latin hierarchs, including the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem besides those of Venice and Lisbon, would be a worthy gesture of conciliation and healing of old wounds between the Churches of East and West.”

“Ironically, things in recent years have moved in exactly the opposite direction,” he continued. “The pope, who is the only Latin hierarch who exercises within the West precisely the role of particular stewardship that the Patriarchs of the East do within their traditions, has renounced the title; and some within the Catholic Eastern Churches who seem to deserve the title on the same ecclesial and historical grounds as their non-Catholic counterparts (thinking here principally of the Major Archbishops of the Ukrainian and Syro-Malabar Churches) are being denied the title.”

Fr. Machado, on the other hand, sees no harm in maintaining the title which, he says, “dignifies the diocese, rather than the person.”

“It is very closely related to the history of the Lisbon Church, but it is a tradition, an honorific, and nothing more than a historical reference. Lisbon has this history, and we are heirs to our history. I understand that it might all seem exotic to someone from outside, but it is just a title, nothing more.”

Others complain that the title generates confusion, leading Catholics in Portugal to mistakenly think that because he is a patriarch, the archbishop of Lisbon has authority over all Portuguese Catholics.

But Fr. José Patrício of the northern diocese of Lamego, former rector of the Pontifical Portuguese College in Rome, thinks that confusion would exist even without the title of patriarch.

“The fact that he is traditionally a cardinal, and the fact that he is bishop of Lisbon, which is the capital, means that people who don’t know better will tend to think that he is the leader of the Portuguese Church, regardless of whether he is a patriarch or not.”

Patrício also noted the possibility that the existence of a patriarchate could breed resentment among those from other dioceses, but he argued that the historical significance of the patriarchate outweighs these risks.

“History matters, and this title is also a way of recognizing the services rendered by the Church of Lisbon throughout the centuries, as a bridge that it was to the rest of the world, and that it can still be in the future, as the pope highlighted during World Youth Day,” he said.

“Of course, we have to purify our vision, so that it doesn’t take the form of careerism, and people don’t strive for titles, but one thing I can be sure of is that neither the current patriarch nor his predecessor were that type of person at all.”

Pope Francis, for all his reputation as a reformer and a defender of a simpler style, has given no hint whatsoever that he is thinking of abolishing the title.

For now, the title lives on.