Why India’s bishops want to get out the vote

Church leaders are anxious ahead of India’s six-week long general election.

When Catholic bishops issue pre-election messages in Western countries, they often limit themselves to general remarks about the importance of voting for the common good.

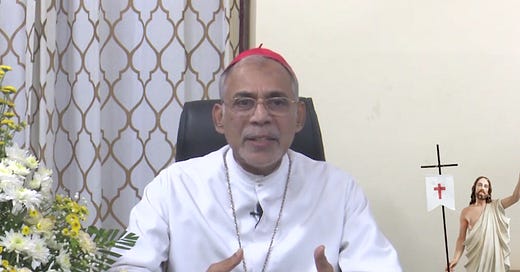

But when Cardinal Filipe Neri Ferrão issued advice April 15 ahead of India’s general election to Catholics in his Archdiocese of Goa and Daman, he was very specific.

Members of his flock who planned to take the 9 a.m. South Western Railway service from Goa’s Vasco-Da-Gama railway station to Velankanni on Monday, May 6 should think again, he suggested.

The weekly train is filled with pilgrims bound for Velankanni’s Basilica of Our Lady of Good Health — dubbed the “Lourdes of the East” — a roughly 800-mile trip taking 27 hours, with 25 stops.

Why would a cardinal discourage pilgrim travel? Because May 7 is the day that citizens in Goa, the smallest of India’s 28 states, go to the polls. If Goan Catholics are in Velankanni, in the state of Tamil Nadu, they evidently won’t get to the ballot box that day.

“It is clear that Catholics moving out with family and friends on a holiday or even going on a pilgrimage on election day, thereby abstaining from the responsibility of participating in the voting process on May 7, 2024, would be not only doing a disservice to the nation, but failing seriously in their important civic responsibility,” the cardinal wrote.

What if Catholics have already booked their tickets on the Velankanni Express? Ferrão addressed that, too.

Cancel the trip, he said, because it’s worth losing some money “for the sake of the greater good and the sacred duty of exercising one’s franchise on election day and thus being positively responsible towards the greater good of the nation.”

The soft-spoken cardinal, who was elected president of the Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conferences (FABC) in February, is not the only Indian Church leader issuing careful recommendations ahead of the general election, the world’s largest exercise in democracy.

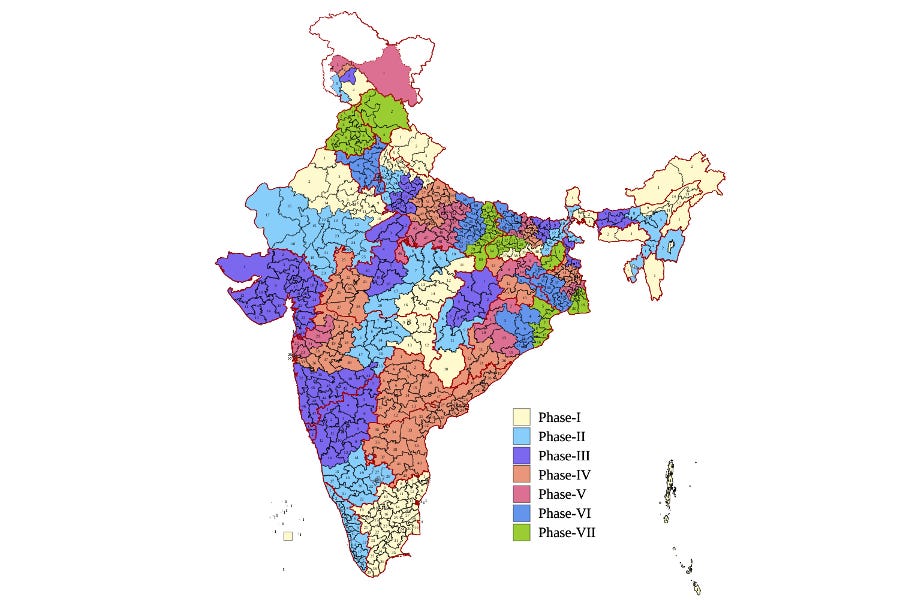

India’s more than 1.4 billion-strong population will head to the ballot box in seven waves between April 19 and June 1. By the end, voters will have elected 543 members of the Lok Sabha, the lower house of the country’s parliament.

Minorities under threat

Many Catholic leaders have adopted a stark and urgent tone ahead of this year’s election.

That’s because polls are predicting a big victory for the National Democratic Alliance (NDA), led by the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). A triumph over the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA) would ensure Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s election for a third term.

Since Modi came to power in 2014, representatives of India’s religious minorities have complained of rising intolerance.

At the start of 2024, the advocacy group Open Doors named India as the 11th worst country in the world in which to be a Christian, describing persecution levels as “extreme.”

“Christians around the nation of India find themselves increasingly under threat,” it said. “This hostility is often driven by an ongoing belief among some Hindu extremists that Indians ought to be Hindu — and any faith outside of Hinduism is not welcome in India.”

The United Christian Forum for Human Rights, an Indian ecumenical monitoring group, recorded 161 cases of anti-Christian discrimination and persecution in the first 75 days of this year.

Almost 30% of the incidents occurred in Chhattisgarh, a central state notorious for anti-Christian animus, but threats were recorded in 19 out of India’s 28 states.

Just this week, a mob vandalized a Catholic school and assaulted a priest in the southern Indian state of Telangana, following claims about the school’s stance on Hindu students wearing religious clothing.

The ‘sin’ of not voting

In February, the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of India (CBCI) expressed alarm at the worsening climate for religious minorities.

“There is an unprecedented religious polarization which is harming the cherished social harmony in our country and endangering democracy itself,” noted the body bringing together India’s Latin Catholic, Syro-Malabar, and Syro-Malankara bishops.

“Destruction of homes and churches, harassment of personnel serving in orphanages, hostels, educational, and healthcare institutions on false allegations of conversion have become common.”

The CBCI declared a day of prayer and fasting for peace and harmony in the country ahead of the elections.

The bishops also highlighted the preamble of India’s constitution, which envisages the country as a “sovereign socialist secular democratic republic” committed to justice, liberty, equality, and fraternity.

“We urge all citizens to enroll as voters and exercise their sacred duty to vote wisely so that we elect leaders who are committed to constitutional values and to the uplift of the poor,” they said.

This stress on the importance of voting runs through Indian bishops’ election messages to their flocks.

In an April 7 address, Bangalore’s Archbishop Peter Machado went as far as to say that “it is a sin if we don’t vote.”

Like Ferrão, the archbishop suggested that Catholics “should take time out by canceling all other engagements on the day of voting.”

Machado, who is based in the southern Indian state of Karnataka, outlined the profile of an ideal candidate.

“Choose a leader who is secular, non-communal, believes in the constitution, and is less corrupt,” he said.

In this context, of course, “secular” means committed to a political order that does not favor any one religious group, rather than anti-religious.

Modi’s outreach

As ever with India, there are plenty of nuances. Although Modi is seen as a champion of Hindu nationalism, he has, at times, sought to reach out to the country’s Christian minority.

He was photographed warmly embracing Pope Francis in 2021. He visited Delhi’s Sacred Heart Cathedral on Easter Sunday 2023 and welcomed more than 100 Christian leaders to his official residence on Christmas Day.

For some Indian Christians, this has the whiff of electioneering. They argue that Modi is seeking to win minority votes without making a substantial effort to curb the violence. Other Christians are grateful for any form of recognition from the man who has dominated Indian politics for the past decade.

Meanwhile, it would be wrong to think that India’s roughly 20 million Catholics take their shepherds’ election advice unquestioningly.

Ferrão’s election message, with its remarks on train travel, caused a stir among Goans, according to Verghese V. Joseph, editor-in-chief of the website Indian Catholic Matters.

In an April 18 op-ed, he asked why the cardinal did not address the voting public’s disillusionment with Goa’s political establishment.

“The question remains: why are religious leaders veering into the political arena, reminding the laity of their electoral responsibilities when they have not taken a similar position against corruption and political manipulation?” he wrote.

“The laity, who are not naive, are fed up with Goan politicians, and they expect their religious leaders to take a more proactive role in highlighting these critical issues.”

But Ferrão is unlikely to regret his “get out the vote” message. Yes, Christians are a tiny minority in India. The 2011 census (the most recent available) found that 79.8% of the population is Hindu, 14.2% Muslim, and 2.3% Christian, and 1.7% Sikh.

But Christians are concentrated in certain parts of the country. In the cardinal’s home state of Goa, for example, 29.86% of the population is Christian. In the southern Indian state of Kerala, Christians account for 18.38%.

So in some places, Christians could have a degree of influence on the general election. But only provided they vote.

I don't know the overall voter turnout, but if Catholics in Goa did turn out en masse, 30% of the population would play a decisive role in the outcome.