What’s the problem with Freemasonry, anyway?

The bishops of the Philippines issued a clarification that Catholics still cannot join the Masons. But why not?

The Catholic bishops of the Philippines reminded Catholics last week that the Church prohibits its members from becoming members of Masonic lodges.

The bishops’ “clarification” was issued March 24 by the Episcopal Commission for Doctrine of the Faith of the country’s bishops’ conference.

It followed reports that a growing number of Freemasons have been participating in local Catholic liturgies and events, including the parish and diocesan phases of the global synodal process, held in the country last year.

The bishops of the Philippines have “always maintained and defended the official Catholic (magisterial) position on the unacceptability of Masonry,” the commission wrote, “including the provisions of canon law on penalties that Catholics incur by joining Masonry.”

The clarification explained that the country’s bishops had in previous decades asked for the Vatican to clarify the position of the Church regarding Freemasonry, undertaken an extensive dialogue with the local Grand Lodge, and even petitioned for an exemption from the universal canonical penalties imposed on Catholics becoming Masons.

But, the commission reiterated, those efforts have always been denied and “the Church’s official position still stood.”

The bishops also noted that while the local hierarchy has always “shown ‘openness’, in the exercise of pastoral circumspection, towards Catholics who may have unwittingly in good faith sought membership in Masonic associations with the best of intentions,” there has never been any doubt about Freemasonry’s “serious errors both in doctrine (philosophical tenets) and practices.”

But what, exactly, is the Church’s problem with Freemasonry? And does the Church really still have laws against it?

The Pillar explains.

A little history

Freemasonry likes to pretend it has links going back to all kinds of weird points in history. If you read Masonic lore, you’ll run across claims that Freemasons built the pyramids, and Solomon’s temple, and all sorts of other stuff.

The real history is this: there were medieval trade guilds, including for stonemasons, dotted throughout Europe over the centuries.

The guilds had levels of membership which reflected a worker’s ability and education in the trade — apprentice, master and so on. Since literacy wasn’t exactly universal, and the postal system wasn’t exactly reliable, these trade unions gave their members secret handshakes and passwords, so when they arrived at a new job site, they could prove their professional qualifications.

Over time, membership of those guilds of stoneworkers dropped a lot. A lot of that had to do with a fall in demand for big building projects like castles and cathedrals, and some of it had to do with people becoming a lot less mobile across the continent. The Reformation actually influenced both of those factors.

Anyway, in the U.K., Masonic lodges needed to find a way to get some new members in to start paying dues and they started allowing non-stone workers to become members. As a selling point, they played up the legends, the secret handshakes, and the private clubhouse aspects of the lodges, and the long and short of it is they began attracting exactly the kinds of people who’d like that sort of stuff: alchemists, pseudo-philosophers, political dissidents, religious non conformists, that sort of thing.

The transformation from network of trade unions to gnostic secret societies took a while, but the formal beginning of Freemasonry as people think of it now was in 1717, when the first Grand Lodge was founded in the back room of a London pub.

From there, Masonic lodges started popping up all over the place. In the beginning, Catholics joined, too — Francis I of Austria was even a patron — since the Church hadn’t said anything about it, one way or another. That changed in 1738, when Pope Clement XII banned Freemasonry as promoting religious indifferentism — the idea that it doesn’t matter what you believed about God, as long as you are a good Mason, because everyone in the lodge was serving a higher notion of natural virtue.

From Clement until the promulgation of the first universal Code of Canon Law in 1917, eight popes issued encyclicals or papal bulls denouncing Freemasonry and imposing a penalty of automatic excommunication reserved to the Holy See for any Catholic who joined.

During those centuries, a lot changed between the Church and the Freemasons. But a lot of what the Church said about why Catholics couldn’t join stayed the same.

Plots and revolutions

Masonry sometimes likes to describe itself as a “society with secrets” not a “secret society.”

Either way, the Church has always condemned the idea of Freemasonry because it removed Catholics from legitimate ecclesiastical oversight while they were being, effectively, catechised into a new philosophy — a different way of looking at the world.

When the Church’s leaders first spoke about Masonry as “plotting against the faith,” they meant that the Masonic worldview was subverting the teaching of the Church for Catholics who joined, and teaching them that it was equally valid to be a Catholic, a Protestant, some other religion entirely, or nothing at all — and that it was becoming a Mason, not being baptized, which would lead to a person’s spiritual and moral fulfillment.

In Catholic countries, like Spain and the states of the Italian peninsula, the lodges got very political indeed.

Masonic secret societies were banned by both the Church and civil governments. In turn, both Church and states were opposed by Masons, often with equal vigor and even violence.

Despite what you may have heard, there’s really not much evidence — if any — that Masonic lodges had anything to do with starting the French Revolution.

But, in what would eventually become “Italy,” the Masonic lodges of the Carbonari (charcoal merchants) operated as revolutionary cells against the papal states and other governments, and engaged in acts of what we’d today pretty easily label terrorism.

Indeed, the architects of the modern nation-state of Italy, the mercenary Giuseppe Garibaldi and Victor Emmanuel, who became the first “king of Italy,” were both Masons — Garibaldi himself founded the Italian Grand Orient Lodge, and served as grand master for several years.

While the Church absolutely condemned violent revolutions, and warned that secret societies fomented such things, popes continued to ban Freemasonry primarily because of its philosophy, not its politics.

In 1821, Pius VII’s apostolic constitution Ecclesiam a Jesu Christo repeated the papal ban on Masonic societies like the Carbonari, and denounced their efforts to overthrow the papal states. But, the pope was also clear, the bigger threat came from the Masonic philosophy of religious indifferentism, and promotion of what we’d today call “secularism.”

In one of several encyclicals condemning Freemasonry’s aims, Leo XIII took specific aim at the secuarist agenda which, he said, included “the State, which [Masonry believes] ought to be absolutely atheistic, having the inalienable right and duty to form the heart and the spirit of its citizens,” as well as the treatment of marriage as a merely civil contract which could be dissolved at will.

According to Leo, part and parcel of Masonry’s core belief in religious indifferentism was the need to exclude the Church from all aspects of civil society and its institutions, including schools, hospitals, charities, universities, and political debate.

That, the pope said, had to be opposed.

Meanwhile, in America, Masonic lodges openly opposed the opening of Catholic schools, the election of Catholics to public office, and in some cases jointly endorsed anti-Catholic candidates and legislation along with local branches of the Ku Klux Klan, including into the twentieth century.

Ritual and religion

Freemasonry often says of itself that it isn’t a religion, that it's just a society of men who value fellowship and cooperation and natural virtue, whatever their different religions may be. Actually, though, modern Masonry’s chief architect, James Anderson, defined it in his 1728 Masonic constitution as “That religion in which all men agree.”

And there are a lot of Masonic rituals which the Church considers to be pretty religious in tone, even kind of quasi-sacramental.

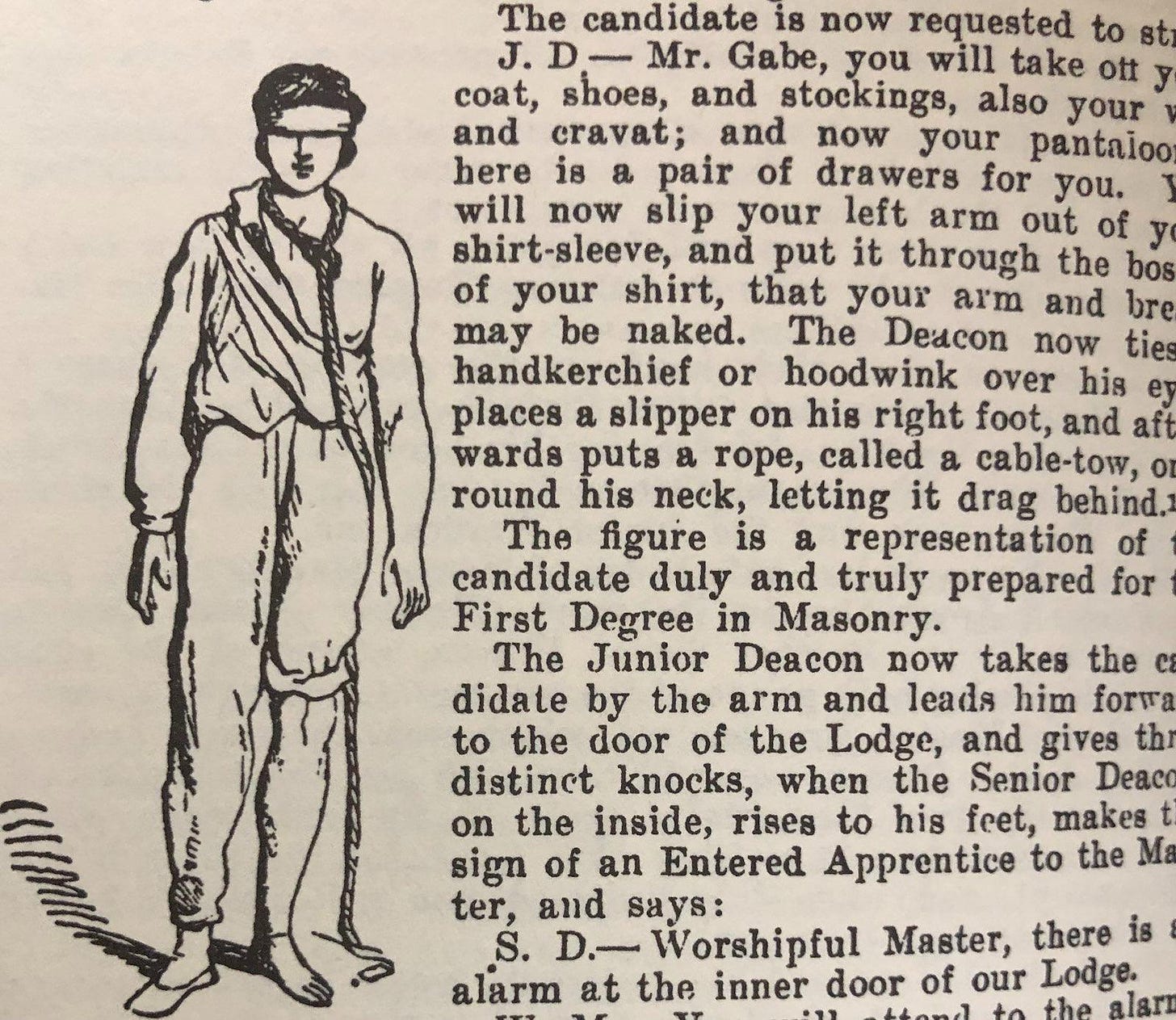

The first ritual of initiation in Freemasonry, to become an “entered apprentice,” for example, involves the applicant stripping down and removing any articles he may be wearing, like a wedding ring or crucifix. Then he’s told to get half dressed, wearing a shirt on his right side, one trouser leg rolled up, one slipper and blindfold.

Then a noose is placed around his neck and he’s led into the lodge hall where he’s announced as “Mr. X, who has long been in darkness and now seeks to be brought to light.” The candidate is then told to embrace the “principle of Freemasonry that the natural eye cannot perceive of the mysteries of the Order until the heart has embraced the deep spiritual and mystic meanings of those sublime mysteries.”

For his part, the aspiring apprentice also affirms that he is in search of “the light” which only Masonry can give him. The rest of the ritual involves moments where the candidate is made to process through the hall blindfolded (sometimes at swordpoint), kneel, be prayed over, and eventually be admitted to the lodge.

Sound pretty normal so far?

Well, the Church — including eight popes — thought that this ritual represents a kind of quasi-renunciation of the faith for a Catholic, a sort of apostasy (total defection from the faith) or at least a heresy against the graces of a person’s baptism, and against the Church as the minister of salvation.

And the further the candidate advances in Masonry, the weirder (and more explicitly anti-Catholic) the rituals get.

In the third degree ceremony, the candidate is put through a pantomime of being killed and resurrected.

And in the thirtieth degree of the Scottish Rite (which is actually American), the Mason is presented with a skull wearing a papal tiara and told it “represents the tiara of the cruel and cowardly pontiff” and “is therefore the crown of an imposter.” At one point in the ritual, a senior Mason stabs the skull with a dagger, while the candidate yells “Down with imposter, down with crime,” before stamping on it.

As it happens, the Church thinks doing that sort of thing is bad for a Catholic’s soul.

Vatican II and what happened next

By the middle part of the 20th century, the opposition between the Church and Freemasonry was pretty much universally understood, even by non-Catholics.

But in the decades following Vatican Council II, as the new Code of Canon Law was being prepared, bishops in some places began to ask if all of the papal condemnations weren’t a bit out-of-date.

In Italy, Masonic lodges continued to be at the center of political and criminal scandals, but in some northern European countries, for example, they were broadly considered to be just fraternal clubs. Nobody is advocating for the overthrow of the papal states here, bishops said, so can’t Catholics be allowed to join?

Indeed, one of the reasons bishops in different places, like the Philippines, ask and are asked if there is really still a problem Freemasonry is that people tend filter their questions through the lens of Catholic conspiracy theories: Breathless speculation about international plots and secret Masonic infiltration of the Church’s hierarchy can help sell a lot of books, but if the more lurid Dan Brown stuff isn’t true, many people assume, there isn’t really a problem with Masonry, right?

Well, no.

In the 1970s, the bishops of Germany engaged in a six year dialogue with local Masonic leaders to examine if there was any reason why Catholics shouldn’t be allowed to join. Their conclusion was that, actually, there were a lot of reasons why Masonry remained at odds with the Catholic faith and concluded that “the Freemasons have essentially not changed.”

“Membership places the foundations of Christian existence in question. Detailed investigation of the Masonic rituals and fundamental ideas, and of their current, unchanged self-understanding make clear: Simultaneous membership in the Catholic Church and the Freemasons is incompatible,” said the German bishops.

Meanwhile, in Rome, the committee charged with redrafting the Church’s universal penal law was also fielding questions about whether there really needed to be an explicit law against Freemasonry in the Church anymore.

Debate in the drafting committee went back and forth about whether there needed to be either an explicit mention of Freemasonry in a canon dealing with prohibited societies in canon law, or an automatic excommunication as a penalty. But, while the final version decided to include neither, it wasn’t because the Church’s opinion about Freemasonry had changed — on the contrary.

The minutes and notes of the drafting committee record that the cardinals were concerned that mentioning Freemasons by name would give people too narrow an impression of the ban on “societies which plot against the Church.” They actually worried people wouldn’t know to apply the law broadly enough, to include, as Cardinal Felici put it, all “those associations which are against the faith, against the doctrine of the Church.”

But when the new code was promulgated in 1983, without an explicit mention of Freemasonry in the new canon 1374, and without an automatic excommunication attached, a lot of people assumed things had changed, even though they hadn’t.

Still a crime

The day before the new Code of Canon Law came into force, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith issued a clarification of the new law.

“The Church’s negative judgment in regard to Masonic association remains unchanged,” the CDF said, “since their principles have always been considered irreconcilable with the doctrine of the Church and therefore membership in them remains forbidden. The faithful who enroll in Masonic associations are in a state of grave sin and may not receive Holy Communion.”

The congregation also explicitly ruled out the option of local bishops or bishops’ conferences making up their own mind about local Masonic associations, saying it is “not within the competence of local ecclesiastical authorities to give a judgment on the nature of Masonic associations” which would imply a local kind of Masonry was acceptable.

Since then, the CDF has responded to regular enquiries from different bishops’ conferences asking if things have changed, and the answer has always been the same: no.

But if joining a Masonic lodge puts Catholics in the state of grave sin, and they can’t receive communion, many ask, what about legal penalties? Are such Catholic still automatically excommunicated?

Well, it depends. Although the canon on prohibited societies doesn’t have an automatic penalty attached to it, some canonists would argue that since the popes, the CDF, and the drafting committee for the Code have all been clear that Masonry is against the faith and doctrine of the Church, joining a lodge is actually a double crime of enrolling in a banned association, which is to be punished with a “just penalty,” and committing an act of heresy, which does have an automatic excommunication attached.

But even so, automatic penalties need to be declared by a competent authority in order for them to attain full legal effects, and becoming a member of a secret society isn’t usually a public act, making it hard for a bishop to impose or declare any kind of penalty.

That said, it does happen.

In 2010, the Bishop of Annecy, France received anonymous information that one of his priests, Fr. Pascal Vesin, was a member of a lodge of the Grand Orient of France. Vesin initially denied the charge, and nothing more came of it, until the following year when a leaflet was sent to the bishop advertising a speech the priest was scheduled to give to the local lodge, and billing Vesin as the local curé and a member of the lodge.

A new investigation found Vesin had actually been a Mason for nearly ten years and, while the bishop and several of his brother priests tried to persuade him to repent, the priest refused to quit the lodge and the CDF told the bishop to suspend him from ministry and remove him from office as part of a penal process. Vesin protested, and asked both Pope Benedict XVI and Pope Francis for meetings, but was denied.

Through the last ten years, Pope Francis has continued to hold the ban on Catholics becoming Masons, while the CDF, now the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith, has continued to issue new clarifications to bishops who keep asking if the law has changed — including in the Philippines.

The pope has even spoken about “masonic lobbies” as a problem in the Roman curia and, setting aside the more outlandish claims of conspiracy theorists, it’s not unknown even today for people working in some departments of the Vatican to be quietly approached about joining a lodge.

So, while the bishops of the Philippines may be the latest to have to repeat that the Church’s stance on Masonry hasn’t changed, they probably won’t be the last. And that stance isn’t likely to change anytime soon, either.

The Lawman for the Lord delivers once again!

I'm surprised you didn't mention the Knights of Columbus being formed effectively as the Catholic antidote to Freemasonry, not even as a passing reference of note. It would be an important note for your readership to know: if you want to join something without risk to your faith, join the Knights.