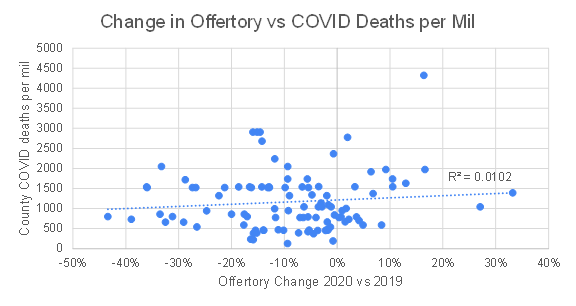

There was no correlation between local coronavirus deaths and the rise or fall of parish offertory income in 2020, while there was a correlation between declining parish revenue and rising unemployment rates.

Those conclusions are among the results of a study conducted by The Pillar, which unpacked the impact of the pandemic on offertory revenue at 100 regionally and demographically diverse parishes across the United States.

Part Two of The Pillar’s report looks to find the factors that contributed to big differences in 2020 revenue shifts among U.S. parishes

Symptoms of the virus

When we began our study, we expected that drops in tithing would correlate closely with the severity of the pandemic in different parts of the country. But the data surprised us.

Our study found no correlation between changes in parish offertory and 2020 county-level COVID death rates.

And while outliers certainly do not tell the whole story, it’s interesting to note that one North Dakota parish, which saw a 16% increase in collections during 2020, is located in the county hardest hit by COVID deaths among all counties in our dataset.

By contrast, the Southern California parish with the largest decline in offertory among those we studied was in a county with a better-than-average death rate; the county suffered 803 deaths per million residents in 2020 — well below the average for our dataset, 1,169 deaths per million residents.

Of course, we wanted to look beyond deaths to measure the impact of the virus, so we analyzed several measures of the pandemic’s regional severity against parish collections. But to our surprise, no available measure of COVID’s local severity had a statistically significant relationship on parish offertory collections.

That result might seem surprising. But in most regions of the country, the percentage of people who actually experienced a loved one with a severe or fatal case of COVID in 2020 was relatively low. For many people, the primary experience of the pandemic’s severity may have come through national news rather than local county statistics.

September unemployment

So what factors do predict the effect of the pandemic on parish finances?

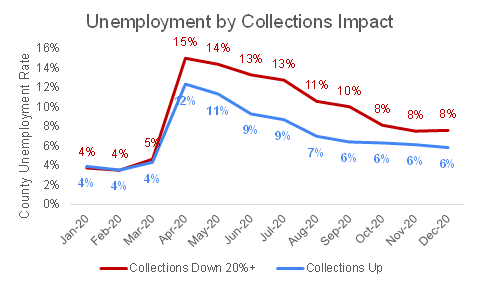

The single most predictive factor of parish revenue is regional unemployment — and, specifically, county unemployment rates of September 2020.

Nearly every county in our study saw unemployment in the double digits in April and May 2020, as most states enacted severe restrictions on gatherings in order to stop the spread of the virus. But some counties also saw employment recover much faster than others.

September 2020 county unemployment rates provided a measure of how well economies were recovering, and the difference for parishes was significant.

A broader picture of the difference in rates of parish economic recovery becomes clear with a look at average monthly unemployment rates in places with very different 2020 parish finances.

We compared unemployment in counties where parishes saw 2020 offertory declines of more than 20% with that of counties where parishes saw an increase in collections:

In short, parishes that weathered the pandemic best were, on average, located in counties where the unemployment rate did not go as high, and where it dropped back down more quickly.

Other predictive factors: Population Density? Education? Lockdowns?

What other factors predict which parishes maintained offertory rates during the pandemic, and which did not?

We examined a number of factors we expected would be predictive, most of which turned out not to be. But we did find one fairly surprising result.

Both a high median income and a high population of affluent people within a parish region seemed likely to correlate with parishes maintaining higher collections. But we found no significant correlation between offertory declines and the median income of the ZIP codes where parishes are located.

The percent of households in the parish ZIP code making over $100,000 per year also had no correlation with 2020 changes to collections.

The percent of the population in a parish ZIP code with a college degree seemed like it might indicate populations with jobs less likely to be furloughed during the pandemic. But, like other factors, education also proved not to correlate with changes in offertory revenue.

An obvious factor to analyze was the severity of state and local lockdown orders. The laws themselves can be hard to measure numerically, but we found a quantitative measure of how much people had actually locked down: cell phone data from Google and Apple showing how much less people used their smartphone mapping apps by month at a county level. That data initially seemed promising, but once we included it with unemployment and demographic data, the mobility data did not provide any additional information about parish giving.

Population density seemed like a very promising statistic. And when we looked at the population per square kilometer of the parishes that saw collections go down more than 20%, versus the parishes where collections increased, we saw there were many more rural parishes among those where tithing increased. Among the parishes in which offertory declined the most in 2020, there were a number of parishes in more densely populated parts of the country.

But when we put all the demographic factors into a statistical tool called a linear regression model, we found that population density simply was not a significant predictor of how collections change. Instead, the model confirmed that September unemployment was by far the most predictive factor.

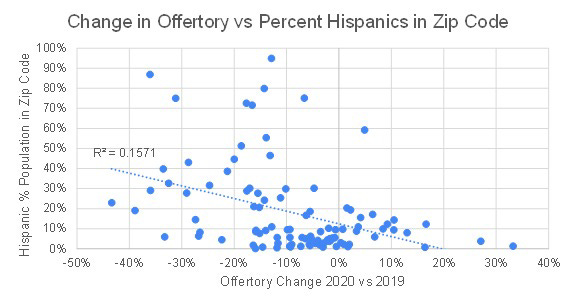

The next most predictive factor was a surprise, and one for which we do not have a clear explanation: the percent of the population in the parish zip code of Hispanic background had a statistically significant correlation to falling parish revenues.

It’s not a very strong correlation, but our linear regression model showed (by a low p-value, if you’re interested in the stats) only a 3% chance that the relationship was random chance.

Some of the hardest hit parishes in our dataset were in heavily Hispanic areas of the Chicago, San Bernardino, and Miami dioceses. Those parishes may represent cases where the local population of Catholics was more vulnerable to unemployment during the pandemic than the population of the area as a whole.

Among the parishes which showed increased collections in 2020, were a number of parishes located in heavily white zip codes in the dioceses of Fargo, Sioux Falls, New York, Orange County, and Fort Worth. And three parishes located in majority Black zip codes in the New Orleans diocese also saw solid increases in their offertory in 2020.

The human factor

The sheer difficulty we had in finding demographic factors to explain the differences in parish collections during 2020 underscores the importance of factors which are specific to individual parishes, and which are not as easily measurable.

We reviewed 10,000 weekly parish bulletins to gather our data. In that process, we noticed some factors that seemed to play a role: Some bulletins talked about the arrival of a new pastor, ongoing stewardship campaigns, parish missions, or emphasis on electronic giving. In parishes mentioning those things, we noticed a better-than-expected offertory performance.

Andrew Robison is president of Petrus Development, a consultant to parishes and other non-profits on development and fundraising. He told The Pillar that even in normal times, parish offertory collections are dependent on the relationship a pastor has with the people of the parish.

At first pass, that might bring to mind images of a pastor on the golf course with a wealthy donor, but Robison painted a different picture.

If a pastor has “relationships with some of his key volunteers and key benefactors for the parish, then a lot of them are going to continue to tithe out of loyalty to him,” Robison said. And the most important kind of relationship to effectively raise funds is a pastoral relationship of trust, he said, and one focused on mission, not fundraising.

“If families still feel like the parish is there for them, and still trying to serve them, they will continue to give and even give a little bit more” during a difficult time, like the pandemic, Robison said.

Robison mentioned parking lot masses or drive up confessionals, or small group ministries that shifted online. Parishes making that kind of shift, Robison said, saw donors increase their commitments as much as they could, because they felt cared for during a trial.

“We teach people that you have to build relationships with your benefactors and with your donors first,” Robison said. “A genuine concern for their wellbeing, and their family’s well-being.”

“If you see [parishioners] as ATMs, or as just a checkbook, eventually they're going to leave. And that’s certainly true when there's a pandemic or a financial crisis. So the parishes that emphasize leadership and relationships are seeing an increase in giving. And they're seeing an increase in activity and enrollment. But the parishes without that, tragically, are suffering, and tithing is a piece of that suffering.”

“One of the lessons that we learned in 2020 is that people weren't necessarily looking for organizations, pastors, or leaders, to shift in a perfect way, but they were looking for leaders being creative and innovative.”

“And the ones that tried — even imperfectly in the beginning— that was appreciated significantly,” Robison said. “Parishioners just wanted to see them adapt.”

“It's just a matter of being creative, innovative, and trying to show your flock, that you still care about them, and you care about their salvation. And when leaders are genuine, then people will continue to support the parish financially.”

Read part 1 of this series here.

If you think reporting like this is important, consider subscribing to The Pillar.