What exactly is sacred music?

What makes music 'sacred'? And why does it matter what music gets played at Mass?

The phrase “sacred music” has gained a lot of traction in Catholic conversations in recent years, with many liturgists and other Church leaders emphasizing the importance of “sacred music” in the Church’s liturgies.

But to the average Catholic in the pew - even one who attends weekly Mass and takes his or her faith life seriously - the meaning of the phrase may not immediately be clear.

What makes music “sacred”? Must it be in Latin? Chanted? Accompanied by an organ? Can any music be sacred if it is intended for use in the liturgy?

And why does it matter what music gets played at Mass?

When Bishop Carl Kemme of Wichita released a pastoral letter on sacred music last fall, he acknowledged that some people might find it to be an unusual topic for a bishop to give his time and attention.

“Some may question why it is necessary to outline a vision for Sacred Music in the Diocese of Wichita. Some may consider other issues to be of greater importance,” Kemme wrote in the letter.

But, the bishop said, he believes a return to the Church’s tradition of sacred music is a key part of renewing liturgical and parish life in the diocese.

“The liturgy is the place, the moment that we can all come together and really encounter God and find graces we need to be his disciples,” Kemme told The Pillar.

“So the liturgy done well, I think, is of absolutely paramount importance, and sacred music is an integral part of that.”

“I've always had this great desire to help in any way that I can to make the music that we use in the liturgy a powerful tool that it can be to encounter and to pray well,” he added.

Kemme’s letter, “Let us sing with the Lord,” invites Catholics in Wichita to shift their mindset “from singing AT Mass to singing THE Mass” – singing the actual texts of the Mass itself.

“I think that's really a key understanding of what I'm trying to convey here,” he told The Pillar.

The bishop asks that Catholics sing the antiphons - the scriptural texts given by the Church to be used at the Mass’ entrance, offertory and communion. He encourages parishes to focus on traditional musical elements, such as Gregorian chant, polyphony, and the organ, rather than attempting “to sanctify popular or secular music, even secular Christian music, by admitting it to the liturgy.”

“[T]he liturgy is meant to be something totally other so that when the priest dismisses us from the liturgy, we can go eagerly back into the world to transform and consecrate the world to God in our daily lives,” he says in the document.

Sacred music has been a passion of Kemme’s for years, even when he was a parish priest before becoming a bishop. He said he has been working to share his love of sacred music with various groups in the diocese for nearly a decade, and decided it was now a good time to share his vision with the entire diocese.

Kemme said he is not aware of other contemporary bishops having written much about sacred music.

But the topic is one that has garnered significant attention in recent years.

The recently created Catholic Institute of Sacred Music in San Francisco has had more than 400 students take online and in-person workshops in its first year alone.

The Sacred Music program at the University of Notre Dame has seen significant expansion in the last decade, creating a new doctoral program, as well as students’ and children’s choirs.

Source and Summit, a company that promotes the use of sacred music in parishes, has grown to some 500 parishes using its resources at Mass in just about three years.

But what exactly is sacred music? How is the genre defined, and what is included in it?

What does the Church actually say about sacred music?

Sacred music is discussed by Pope Pius X in the 1903 motu proprio Tra Le Sollecitudini. The pope lays out three criteria for sacred music: sanctity, goodness of form, and universality.

Sacred music is discussed further in Sacrosanctum concilium, the Second Vatican Council’s constitution on the liturgy, which devotes a full chapter to the subject.

The document describes sacred music as “a treasure of inestimable value” for the Church, and says its purpose is “the glory of God and the sanctification of the faithful.”

“[S]acred music is to be considered the more holy in proportion as it is more closely connected with the liturgical action, whether it adds delight to prayer, fosters unity of minds, or confers greater solemnity upon the sacred rites,” Sacrosanctum concilium states.

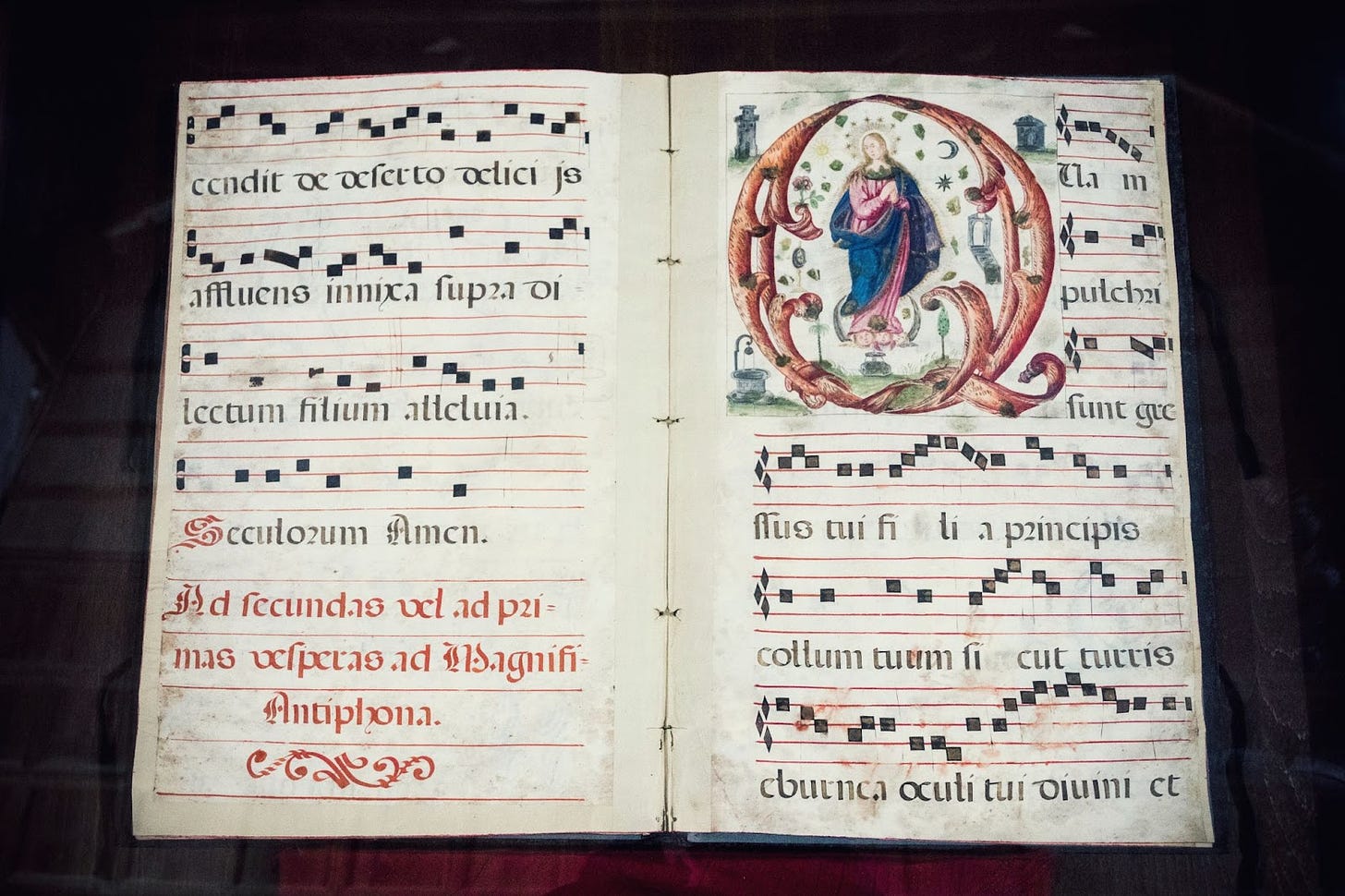

The document gives special recognition to Gregorian chant, which has been part of the Church’s musical tradition for centuries. Gregorian chant is a style of music that sets Latin texts to a monophonic melody, without harmonies or chords. These are sung without the accompaniment of an instrument.

Sacrosanctum concilium says that Gregorian chant is “specially suited to the Roman liturgy” and “should be given pride of place in liturgical services.”

But the Vatican II text also says that “other kinds of sacred music, especially polyphony, are by no means excluded from liturgical celebrations, so long as they accord with the spirit of the liturgical action.”

A few years after Vatican II, Musicam sacram was released as a post-conciliar document, designed to implement what Sacrosanctum concilium had taught about sacred music.

It also notes the importance of Gregorian chant and polyphony, but says other forms of “sacred popular music” are also to be included in this genre.

Musicam sacram defines sacred music as “that which, being created for the celebration of divine worship, is endowed with a certain holy sincerity of form.”

The document offers guidelines about the use of sacred music. It notes several general preferences, but it also allows for significant flexibility in the liturgical music that is chosen.

It says the pipe organ holds a special place in divine worship, but other instruments can also be used, provided that they “are suitable for sacred use, or can be adapted to it, that they are in keeping with the dignity of the temple, and truly contribute to the edification of the faithful."

It says the use of the Latin language should be preserved, unless the competent Church authorities approve of the vernacular.

While it says that “[a]bove all, the study and practice of Gregorian chant is to be promoted,” it also allows for the creation of new works of sacred music, as long as they are fitting with the dignity of the Mass, and follow the general principles of the Church’s established sacred music tradition.

Gregorian chant and “sacred popular music.”

The pipe organ and other instruments.

Latin and the vernacular.

When it comes to defining sacred music, balancing these ands is where the rubber meets the road — and where scholars of liturgical music have developed differing viewpoints about the ideal type of music to be used at Mass.

Fostering a contemplative spirit

Rick Wheeler is the artistic director and founder of Gaudium Verum, a Denver-based group that executes chant, polyphony and choral works.

Wheeler told The Pillar that he wanted to “start a group where you have meticulously professional, unified singers coming together and singing high polyphony and chant for liturgy.”

He initially got together a group of musicians in 2019. They were shut down by the Covid pandemic in 2020, but reunited as soon as they could.

Video: Tantum Ergo, sung by Gaudium Verum

Today the group sings at Masses, prayer services, and Vespers around Denver. The group also does educational outreach and training for pastors, choirs, and music directors.

Wheeler said the group has seen strong interest and powerful reactions, particularly among young people, who may never have heard Gregorian chant at Mass.

He would like to see pastors incorporating more Gregorian chant and polyphony into their Masses.

He’s not opposed to other types of music in the Mass, though. He said the Vatican II documents discussing Gregorian chant having “pride of place” in the liturgy are often understood to mean that at least 50% of liturgical music should be Gregorian chant.

“The music of the Church, first and foremost, is chant, then it's polyphony, then it's hymns and local customs. And, unfortunately, in America, we turned that around,” he said.

Wheeler suggested that as long as chant and polyphony are appropriately prioritized in this way, there can also be a variety of other musical styles included in the Mass under the category of “hymns and local customs.”

But not all styles of music are fitting for the liturgy, Wheeler cautioned.

While there are technically no styles of music that are explicitly forbidden in the Mass, he said, the purpose of liturgical music is to elevate the soul, so hymns should be selected with that criterion in mind.

Wheeler noted that Gregorian chant was “designed not to excite the passions but to elevate the soul.”

“It appeals to the natural sense of beauty that humans have. And that's the idea is that there's a spiritual beauty in its movement, and as a result it assists prayer, it assists the liturgy, it raises the mind to God. So there's an intellectual movement but a spiritual movement as well.”

There is room for numerous different hymns and cultural songs at Mass, he said, as long as they have this character of elevating the soul in prayer.

Music that excites the passions is a distraction from this contemplative spirit and should be avoided at Mass, Wheeler said.

“When you have something that is raucous and bounces off the walls pretty hard,” he said, “you have something then that takes away from that contemplative spirit.”

“For example, I love Van Halen, because I grew up with them, but I wouldn't play them at Mass.”

Embracing musical diversity

Music educator and published composer Christian Leanos takes a different approach to liturgical music.

Leanos is the pastoral associate for music and liturgy at St. Camillus Catholic Church in Silver Spring, Maryland. He is also the music director for Hispanic ministry at the Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle in Washington, D.C.

He told The Pillar that he believes no style of music should be off-limits for Mass.

“All forms of liturgical music should find a welcoming place in the Catholic Church, and we should wholeheartedly embrace this diversity,” he said.

“However, before selecting any hymns or music, it is crucial to understand the unique identity of our parish. This approach ensures that our musical choices serve the congregation effectively, fostering a connection rather than imposing on them.”

Leanos said that he embraces a range of musical styles in his liturgical planning, as long as the music is “composed with the intent to be used in our sacred celebrations.”

“Whether traditional or contemporary, the primary consideration is that the music enhances the worship participation and contributes meaningfully to our liturgical celebrations where everyone feels welcome and at home,” he said.

Video: Music from the Easter Vigil at St. Camillus Church in Maryland.

Leanos believes the documents of the Church since Vatican II support his approach.

Musicam sacram states: “No kind of sacred music is prohibited from liturgical actions by the Church as long as it corresponds to the spirit of the liturgical celebration itself and the nature of its individual parts, and does not hinder the active participation of the people.”

That statement means a lot to Leanos.

“This openness supports the incorporation of diverse instruments that can enhance the worship experience and resonate with the faith community, embracing the richness of musical expression while staying true to the sacred nature of the liturgy,” Leanos said.

“When incorporating different cultures into the Mass, the Catholic Church encourages a respectful integration of diverse musical traditions,” he said. “This involves adapting sacred music to reflect the cultural richness of the community while maintaining the core values of reverence and worship.”

Embracing all styles of music does not mean there are no criteria for selecting songs, Leanos clarified.

“Sacred music in the Catholic Church is expected to possess qualities such as reverence, solemnity, and a capacity to enhance worship. It should express religious themes, inspire devotion, and align with liturgical context and traditions. Melodic beauty, harmony, and adherence to the liturgical text are also emphasized,” he said.

Selection of sacred music should also be based on “adapting to the necessities of the Church and its parishes, considering the congregation’s needs, and fostering a sense of belonging,” he added.

For example, he said, if a parish has a robust young adult community that regularly takes part in praise-and-worship events, that becomes an element of the parish’s cultural identity, which can be included into the hymns of the Mass.

Leanos said he believes Gregorian chant should be recognized for its “historical significance and solemnity,” but should not be viewed as the only – or even primary – type of music that “aligns with worship, contributing to the reverence and dignity of the liturgical celebration.”

“Regrettably, some musicians insist on a pre-Vatican II approach, but as Catholic pastoral musicians, we shouldn't confine ourselves to a single style,” he said.

“Gregorian chant possesses undeniable beauty, and I advocate for its continued presence in our liturgies. However, as Catholic musicians, we should broaden our musical horizons by embracing various styles.”

Leanos likened the role of Gregorian chant in the liturgy to the role of Latin – an undeniable part of the Church’s tradition, but not the only way to celebrate the Mass.

“While Latin remains the universal language of the Catholic Church, appreciating the beauty of our native tongue is equally important,” he said. “We ought to be bridges connecting the past with the present and paving the way for the future.”

The ‘supreme model’ of sacred music

But Adam Bartlett, founder of the sacred music platform Source and Summit, said Church documents make it clear that Gregorian chant is not intended to be viewed as just one of many types of liturgical music.

Gregorian chant has a special role in the Church’s sacred music tradition, he told The Pillar.

In Tra Le Sollecitudini, Pope Pius held up Gregorian chant as the “supreme model” of sacred music.

Pius also presented a principle for evaluating other types of sacred music, saying: “the more closely a composition for church approaches in its movement, inspiration and savor the Gregorian form, the more sacred and liturgical it becomes; and the more out of harmony it is with that supreme model, the less worthy it is of the temple.”

This primacy of Gregorian chant is also reiterated in Vatican II’s constitution on the liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, which describes it as “specially suited to the Roman liturgy” and says it “should be given pride of place in liturgical services.”

That principle was later reiterated again by Pope St. John Paul II, 100 years after Pius first expressed it.

These texts make it clear that Gregorian chant has a special status in the Church, Bartlett said, and there are several reasons for this, beyond just its long history in Catholicism.

“The texts of Gregorian chant fundamentally are the texts of the liturgy itself, including all of the texts of the Mass and also the divine office and the other sacraments,” he said. “The texts are set to music in Gregorian chant and the musical form in Gregorian chant always takes the word as its primary point of focus.”

In Gregorian chant, he explained, the text is not altered to meet the musical demands.

He pointed to the example in a popular hymn with the lyrics: “Shepherd me, oh God, beyond my wants, beyond my fears.”

The text is an adaptation of Psalm 23, which says, “The Lord is my shepherd. There is nothing I shall want.”

“Many times, there are musical forms that have rhythmic and musical requirements that cause composers to alter the text, but Gregorian chant always takes the word first and gives musical form to it,” he said.

In addition, Bartlett said, Gregorian chant “gives primacy to the human voice.”

“It doesn't require any other instrumentation. When the words of the liturgy - which are the words of scripture, the word of God - are sung, it very really and very truly is Christ's song to the Father, sung through his mystical body, and therefore is vocal music which Christ himself sings. When we sing purely vocal music, we're more closely…reflecting that theological reality.”

Singing the Mass

Bartlett’s understanding of sacred music goes beyond advocating for increased use of Gregorian chant.

He told The Pillar that sacred music is, first and foremost, the sung liturgy itself.

“The ideal form of the liturgy always is the sung form of the liturgy, and the Church states that clearly. The liturgy is meant to be sung,” Bartlett said.

That means not just the hymns at different points in the Mass, but also the texts which make up the Mass — both the propers (the Scriptural texts that change each day, like the Alleluia verse) and the ordinary (the texts that remain the same throughout the liturgical year, like the Gloria and the Creed).

Bartlett said a fully-sung Mass is really the Church’s preference, as expressed in the documents of Vatican II.

Video: A fully sung Mass in Latin Gregorian chant.

Musicam sacram states that “Liturgical worship is given a more noble form when it is celebrated in song.”

While there may be practical constraints on singing the liturgy every day, Source and Summit, the company Bartlett heads, offers resources to encourage sung Masses, in an effort to help parishes “elevate the liturgy” through the use of sacred music.

Among the resources Source and Summit offers are the antiphons of the Mass (proper texts given by the Church for the entrance, offertory and communion) in English – which draw their inspiration from Gregorian chant, but are presented in a more accessible way, so congregations can sing them.

Source and Summit also offers a development of the Gregorian chant tradition, using vernacular text – in English and Spanish – instead of the traditional Latin.

Bartlett said there are moments in the liturgy where hymns can be sung appropriately. The General Instruction for the Roman Missal recognizes the entrance, offertory and communion as particular moments in the Mass where hymns can be included.

But he said the liturgical preference for these moments should be to sing the antiphon from the Roman Missal or the Graduale Romanum, in light of Vatican II’s statement that Gregorian chant should be given precedence in the liturgy.

Still, the documents of Vatican II explicitly recognize that there can be hymns used in the Mass beyond Gregorian chant and polyphony.

Bartlett acknowledged that hymns can be incorporated into the Mass. However, he believes that many of the songs that are popular today would be properly categorized not as liturgical music, but as a form of devotional music or religious singing.

Such music can aid prayer and foster encounter with God, but it is more appropriate for adoration or devotional events such as a Eucharistic procession than it is for Mass, he said.

In Bartlett’s view, praise-and-worship music and many other styles of religious music are generally not fitting for Mass, because they focus on private prayer or cultural expression rather than drawing minds to the realities of heaven and the Mass.

“In the liturgy, there are forms and there is an entire sacramental system of signs and symbols that are meant to draw us into the prayer of Christ, to draw us up and out of all of the particularities of our subjectivity and into an experience of the heavenly liturgy. Music in the liturgy is really ordered toward that end,” he said.

Source and Summit offers a library of hymns for the liturgy that Bartlett described as “time-tested, beautiful and theologically sound.”

In evaluating whether a particular piece of music is appropriate as a hymn in Mass, Bartlett pointed to three defining characteristics of sacred music outlined by Pope Pius X in his 1903 motu proprio: sanctity, goodness of form, and universality.

Sanctity

In his motu proprio, Pope Pius X says sacred music “must be holy, and must, therefore, exclude all profanity not only in itself, but in the manner in which it is presented by those who execute it.”

Bartlett explained that the pope is not using “profanity” in this case to mean things that are obscene, but simply secular – anything “outside the temple.”

He suggested that sanctity means that sacred music should not only be intended specifically for use in the liturgy, but that it should also sound different from other types of music – set aside for use in worship.

“That which is holy is reserved for the worship of God and for our worship of Him within the context of the temple,” Bartlett said. “Other kinds of music that aren't suited toward that purpose, he labels as profane. Not bad, but more suitable to use outside the temple.”

Goodness of form

Pius’ second criterion for sacred music is that it must possess “goodness of form.” The pope says that sacred music “must be true art,” although he does not elaborate on what this means.

While that criterion may sound subjective, Bartlett stressed that Pius was relying on a classically Thomistic understanding of aesthetics, which holds that for a thing to have beauty, it must possess claritas, consonantia and integritas.

From a Thomistic perspective, sacred music has claritas if it helps make the invisible truths of the liturgy as clear as possible, without obstructing them, Bartlett continued.

The Church understands beauty as the splendor of truth - the radiant and attractive power of truth, he said.

“So when music in the liturgy is beautiful, it more effectively draws minds and hearts toward the truth of the reality that they convey.”

He gave the example of the Sanctus, or Holy, Holy in the Mass.

“This prayer has a specific truth, a particular invisible reality that it is meant to convey to us: It is our invitation to be drawn into the heavenly song of praise sung by the angels and saints in the liturgy of the Heavenly Jerusalem. If the music that sets these words is beautiful, it helps us perceive that reality more clearly, and to participate in it more deeply.”

“When we hear and sing the words ‘Holy, holy, holy Lord God of hosts’ our vision of the heavenly liturgy (which is invisibly present in the liturgy) should become clearer,” he said.

“If, though, the music that sets these words sounds more like a Broadway musical or a commercial jingle, our minds will probably not be drawn heavenward, but are more likely to be pulled back into the things of the world.”

Additionally, he said, sacred music has the Thomistic qualities of integritas and consonantia when it is transcendent and directs people heavenward, in accordance with the purpose of sacred music.

Universality

The third characteristic of sacred music listed by Pope Pius is universality, which he describes as flowing naturally from the traits of sanctity and beauty. He says that “nobody of any nation may receive an impression other than good on hearing [sacred music].”

“There's a sacred character,” Bartlett added. “There's goodness that we perceive in it. It has a transcendent quality. I think that we can see that when people encounter it and experience it.”

Bartlett said he has seen cases of people from different cultures around the world being fascinated and awed by the musical tradition that has grown out of the Church’s liturgy.

“There have been commercial phenomena with Latin Gregorian chant. There was a chart-topping record in the '90s called ‘Chant,’ and people had no idea what the words meant or even what it was that they were listening to, but they heard it and said, ‘Wow, there's something really beautiful and very good here. Even though I'm not familiar with it, I'm drawn to it and it has this universal attractiveness’.”

“That's really the criteria that Pope Pius X gives us. He doesn't imply that it has to be familiar but it needs to leave us with the impression that this is good, that it is sacred and that it's beautiful.”

Still, not everyone loves Gregorian chant or polyphony. Bartlett reiterated that rather than a matter of subjective preference, the idea is that “if anyone from any culture hears sacred music, they should be able to perceive beauty and sanctity in it intuitively.”

‘A sacred encounter’

For his part, Bishop Kemme also acknowledged that some people may not like certain types of sacred music.

And that’s ok, the bishop said.

“The liturgy really goes beyond everybody's personal preference. It's the whole Church at prayer,” he told The Pillar. “[It’s] something that the whole Church embraces - not just one particular cultural expression or something like that, but something that's…universally understood.”

He thinks that even if people do not find Gregorian chant or polyphony personally appealing, they will still have a “sense of encountering something marvelous” through it.

At the same time, Kemme said he wants to allow for the musical traditions of other cultures, which may be “fundamentally different” but can also facilitate an experience of encountering the transcendent.

“There are so many different cultures that have left their mark on our liturgy,” he said. “I think it's not a matter of one or the other… it's really blending them and bringing out the best of both that I think we can get the best experience of the liturgy.”

There is not just one right way to implement sacred music, the bishop said.

“It's a great work in progress, but it's an important movement, I think, into our future, and I think it can have a profound effect on the vitality of the Church.”

To Bishop Kemme, ongoing education and formation are a crucial part of implementing sacred music in the Diocese of Wichita.

“We really need to give our people, especially our musicians, as well as our pastors, our priests, and the lay faithful, a deeper understanding, a deeper formation of why liturgical music is so very important and how to make it bear more fruit in the offering of the Mass,” he said.

The diocese is providing resources for parishes that are working to make a transition toward this vision of sacred music. Kemme said the office for worship has held a formation day for pastoral musicians and a workshop for musicians in the Hispanic community. These formation opportunities will be ongoing, he said.

Even priests need formation in order to properly understand sacred music, and to incorporate it into the Mass, Kemme said.

He said the diocese’s seminarians receive a much better formation in sacred music than he received when he went through seminary.

“I think the seminaries are doing a much better job today in forming future priests to be able to sing the Mass if at all possible, and to help our people understand the importance of the sacredness, the transcendence, the solemnity of the music that takes place in the Mass,” he said.

“Our seminarians in general are really open to this,” he added. “They're very much attuned to this movement in the Church in terms of sacred music, and they're kind of almost demanding it, in a good way.”

Overall, Kemme said he has seen a generally enthusiastic response to his pastoral letter. He said people are grateful for the clarity and direction provided. The Wichita cathedral has already adopted many of the ideas in the pastoral letter, and a few other parishes are in the process of doing so as well. Some parishes are using resources from Source and Summit, which Kemme described as a helpful source of formation.

But there has also been some hesitancy, he acknowledged.

“Change isn't always easy, and so people are accustomed to doing things the way they've done them for a long time… making even smaller slight changes can be just a little uncomfortable,” he said.

The bishop said he doesn’t expect parishes to adopt everything in his pastoral letter overnight.

“I expect this to take years to really evolve and to develop,” he said. “I hope that in time that when people come to the liturgy here in this diocese, that they will be given a blessing of entering into a sacred encounter and a real life-changing moment in their week, especially the Sunday celebration of the Mass. And I just really believe with all my heart that sacred music has a profound part to play.”

I appreciate the effort to get more than one opinion on this topic, and especially speaking with Adam Bartlett was a good choice. I do have to quibble with one of the quotes, though:

"Leanos said he believes Gregorian chant should be recognized for its 'historical significance and solemnity,' but should not be viewed as the only – or even primary – type of music that 'aligns with worship, contributing to the reverence and dignity of the liturgical celebration.”'

Except that it's in contradiction to what the documents on the liturgy actually say: “the Church acknowledges Gregorian chant as especially suited to the Roman liturgy; therefore, other things being equal, it should be given pride of place in liturgical services.” (Sacrosanctum Concilium 116).

I agree that should not be viewed as the only type of music allowed, but to claim that it is anything but primary is to contradict every official liturgical document on music either before or since Vatican II.

I have it on good authority that the best music for Mass is the music that old people tell us the young people want to hear.