What Berlin’s archbishop said about same-sex blessings

The Archbishop of Berlin has caused a stir beyond the borders of his archdiocese.

A letter from the Catholic Archbishop of Berlin addressing same-sex blessings is causing a stir far beyond the borders of his archdiocese.

In the Aug. 21 letter, Archbishop Heiner Koch assures the Berlin archdiocese’s priests, deacons, and lay pastoral workers that he will not take disciplinary action against them if they bless couples “who cannot or do not want to marry sacramentally.”

In the almost 2,000-word letter, he offers a detailed explanation for his decision, which he says he has taken in view of strong disagreements within the archdiocese, which serves around 373,000 Catholics.

What does Archbishop Koch say, exactly? What’s the context? And what will happen next? The Pillar takes a look.

What’s the context?

It’s probably best to start with the context, since that is where Koch’s letter begins. He notes that since Germany’s “synodal way” formally concluded in March, Catholics in the Berlin archdiocese have been discussing how to implement its resolutions.

Among the documents endorsed by participants in that initiative — which brought together the country’s bishops and select lay people for three years to discuss hot-button issues — was one entitled “Blessing ceremonies for couples who love each other.”

The four-page text called on Germany’s bishops “to officially allow blessing ceremonies in their dioceses for couples who love each other and want to commit themselves, but to whom sacramental marriage is not accessible or who do not want to enter into it.”

The document underlined that “this also applies to same-sex couples on the basis of a re-evaluation of homosexuality as a normal variant of human sexuality.”

The resolution contradicted a 2021 Vatican declaration, approved by Pope Francis, that “the Church does not have, and cannot have, the power to bless unions of persons of the same sex.”

Alongside the synodal way, there are two other contextual factors worth mentioning.

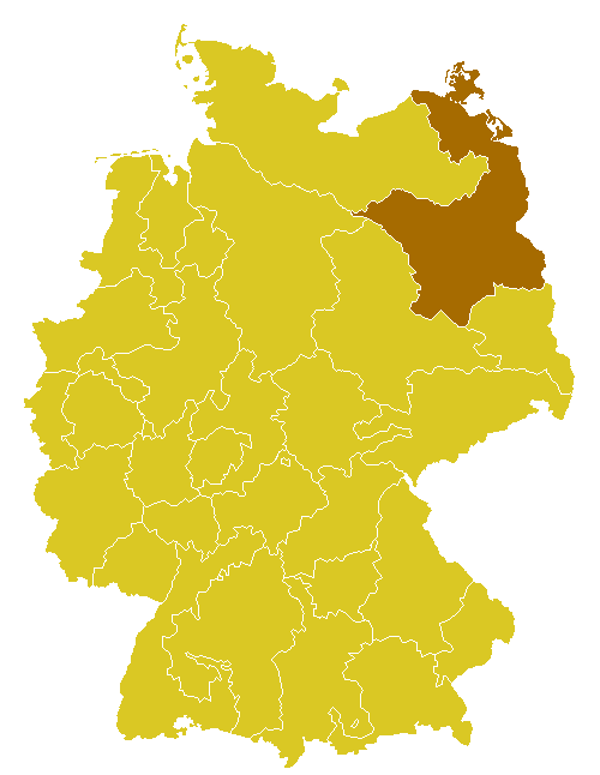

First, Berlin is often listed as one of Europe’s most welcoming cities for people who identify as LGBT. The Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, described as the world’s first LGBT rights organization, was founded in the city in 1897. Hundreds of thousands of people took part in the annual Berlin Pride parade in July. In 2022, Koch appealed for forgiveness for homophobia in the Church, a gesture that nodded toward Berlin’s position as a global LGBT center.

Second, German Catholic media are currently giving ample coverage to a situation in the Archdiocese of Cologne — another city with a strong LGBT presence — in which a pastor claims he was reprimanded after he held a blessing service for “all couples who love one another” at his parish in March — Archdiocesan authorities dispute his account.

The German dioceses of Münster, Aachen, and Essen — located within the ecclesiastical province of Cologne — reportedly responded to the case by declaring that they would not impose sanctions on priests conducting similar services. So the question of disciplinary action is topical in the German Church.

What does Archbishop Koch say?

Koch notes in the letter that he is committed to implementing the synodal way’s resolutions in the archdiocese, as long as they do not “go against the intentions and instructions of the Holy Father.”

He says that not long after the initiative’s final assembly, debates broke out in the Berlin archdiocese over the resolution on same-sex blessings.

“The proposal to introduce blessing services for couples who love each other and who cannot or do not want to marry sacramentally in our diocese has triggered controversy and discussions, some of which were conducted with great severity and strong emotions,” he writes.

Koch, who has served as Archbishop of Berlin since 2015, says that while the discussions were marked by “great love” for the Church, “not infrequently the conviction emerged that only one’s own point of view was suitable to protect the Church from dire consequences.”

Koch then lists the reasons why some Catholics in the archdiocese oppose the blessing services, followed by the reasons that others support them.

He notes that opponents believe that same-sex unions are not ordered to God’s plan as inscribed in creation and fully revealed by Christ’s Incarnation and therefore cannot be blessed. He cites the Vatican’s 2021 declaration in a footnote.

The archbishop then says that supporters’ “well-thought-out” arguments include the conviction that the Church is always developing in the knowledge of God, and that it should recognize through blessings the good elements in committed partnerships, such as love and fidelity.

Koch then reflects on Pope Francis’ 2016 post-synodal apostolic exhortation on love in the family, Amoris laetitia.

He notes that Amoris says that same-sex unions “may not simply be equated with marriage,” and he suggests that Amoris also gives local churches “a great deal of latitude in dealing with people in so-called ‘irregular’ situations.”

Koch argues that Francis’ oft-cited statement about the Eucharist in his 2013 apostolic exhortation Evangelii gaudium — that it is “not a prize for the perfect but a powerful medicine and nourishment for the weak” — also applies to other sacraments, including marriage, “and yet even more so to a sacramental such as blessing.”

“Every blessing promises God’s grace and help to us people who are and remain weak. Blessing therefore does not have the meaning of ‘legitimizing, endorsing, approving,’” he writes.

“As the blessed, we all remain guilty people who need God’s uplifting grace for our life’s journey. This basic statement connects all people, even those who ask for blessings for their relationships that have not been or cannot be formed sacramentally.”

The archbishop then sets out six points which can be summarized as follows:

Given the sharp disagreements over blessing services, each priest, deacon, and full-time pastoral worker should “make a carefully considered decision for themselves.”

As long as there is no ruling apart from the Vatican’s statement in 2021 (which the letter mistakenly dates at this point to 2022), the archbishop will not himself preside at such blessing services.

He notes that the German bishops’ conference is seeking to “intensify talks” on the topic with the pope and officials such as the incoming Vatican doctrinal prefect Cardinal-elect Víctor Manuel Fernández, who has “shown himself open to consideration of a blessing if it is designed in such a way that it does not create confusion regarding the essential difference with the marriage of man and woman.”Koch confirms that “as long as the status quo exists,” he will not take disciplinary action against those who preside at blessing services in the archdiocese.

The archbishop says he expects others to respect the decision of each priest, deacon, and pastoral worker for or against blessing services.

The issue of blessing services should not be used “for political or media purposes.” Neither supporters nor opponents should present themselves as being superior “in the congregation, in church committees, in the press, etc.”

Where there are differences at a parish level, within a pastoral team or a Church institution, Koch expects leaders to seek a solution by following his guidelines. Where they cannot reach an agreement, they should approach him for help.

Koch ends the letter by saying that what he has outlined is “a pastoral path, not an administrative or legal one,” inspired by the statements of Amoris laetitia.

“As there are reasons for and against blessing couples who love each other but do not want to or are unable to marry sacramentally, I would like to encourage you to weigh this question in a nuanced way and to decide responsibly,” he writes, adding that he hopes the archdiocese will “succeed in preserving unity in diversity.”

What’s next?

Given the Archdiocese of Berlin’s prominent position in the German Church, and the worldwide media attention given to German Catholicism during the synodal way, Koch’s letter is likely to be studied by Catholics around the world, including at the Vatican.

Seen from one angle, it highlights the difficulties that German dioceses supportive of the synodal way face as they seek to implement the initiative’s resolutions. From the creation of a permanent “synodal council” to formalizing the laity’s role in the election of bishops, synodal way supporters are encountering formidable practical obstacles.

Viewed from another angle, the letter shows the deep divisions within the German Church. When four diocesan bishops refused to fund a committee intended to implement the synodal way’s resolutions, it was clear that the initiative had split the country’s episcopate. Koch’s letter underlines that there are also profound — and perhaps irresolvable — differences within dioceses, not just between them.

Looked at from a wider angle, the letter suggests that the Vatican is sending mixed (or perhaps not easily intelligible) signals about same-sex blessings. Through phrases such as “as long as the status quo exists” and references to Vatican talks, Koch appears to imply that the topic is in flux.

The Vatican made no public comment when the Belgian bishops issued a text allowing for a ritual blessing of same-sex couples in September 2022. Following the synodal way, the German Church is expected to publish a manual including blessings for same-sex couples. The pastoral care of Catholics who identify as LGBT is likely to feature prominently in discussions at October’s synod on synodality in Rome.

These factors may have been on Koch’s mind as he drew up his guidance, which doesn’t seek to resolve any of the current controversies but rather pleads for a “live and let live” attitude within his archdiocese.

The question is whether his appeal will be heeded — or, perhaps more likely, dismissed as insufficient by all sides. Regardless, the reaction will surely be watched closely in Rome as it grapples with “preserving unity in diversity” on a global scale.

Is it even worth pointing out the failed logic, theology, and moral bankruptcy of the Archbishop's stand here? This topic has been beaten to death so much and the Vatican has shown repeatedly that it has no appetite to act decisively on this matter that I feel that we really will be dealing with this kind of nonsense indefinitely, at least until Pope Francis dies (I don't believe he will ever resign).

The fact that this situation even exists is a failure in the clergy of the Church from the top down - from Pope Francis, for his failure to protect faithful Catholics from heretical bishops and his failure to defend the faith, to the bishops, for endorsing sin and heresy in their dioceses, and to any priests and deacons that go through with such blessings. It would not be so frustrating if this wasn't such a simple matter, but apparently understanding and upholding a basic, biblical teaching on human sexuality is too difficult for a bunch of clerics with advanced degrees in theology and a decade of formation in seminary.

So is the Synod on Synodality now just the Lambeth Conference?