Fr. Tim Finigan is writing a book about the “Four Last Things,” as they’re known in Catholic spiritual writing: Death, Judgment, Heaven, and Hell.

It would be an ambitious project for any writer, but it poses special challenges for the English priest, who has suffered a series of blows to his health in recent years. Following a heart attack, he underwent a bypass operation. He then experienced dramatic weight loss that almost led to his death.

The 64-year-old, a priest of the Archdiocese of Southwark, says he feels better now, but has been left with eyesight problems which mean he can only read around 10 words a minute. It would take him around half an hour to read a single page of an average book, he says.

But Fr. Finigan, author of the popular Hermeneutic of Continuity blog, is technologically adept and uses text-to-speech software instead of reading.

He spoke to The Pillar about the “Four Last Things” via phone, from his home in London. From time to time, he would hit a button and a female computerized voice read out his notes, giving him cues for his answers.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

St. Philip Neri wrote that “beginners in religion ought to exercise themselves principally in meditation on the Four Last Things”: Death, Judgment, Heaven, and Hell.

Why is that a good place for “beginners in religion” to start?

People are concerned about the things of the world ordinarily. That’s most people’s concern: day-to-day stuff. Philip Neri, and all the saints, are concerned with people’s salvation. It doesn’t mean that they’re not concerned about worldly matters, but it means that the most important thing of all is that he wants everyone to get to heaven. And so he has this radical approach in teaching people to pray.

Philip Neri is one example. Most people of that era would have seen the eternal truths as a sensible place for somebody to start if they were coming to faith from a purely worldly life and wanting to become a bit more devout.

St. John Paul II said that the Church cannot omit “a constant catechesis” on the Four Last Things “without serious mutilation of her essential message.”

Why is it important for the Church to still speak of Death, Judgment, Heaven, and Hell?

The most important reason he wants the Church to talk about these is because they’re still true. They are eternal truths and therefore still extremely important for us to consider. He had a series of catecheses on the Last Things and he was criticized. People got a bit spooked by the idea, which shows how far we’ve come.

Until relatively recently, certainly within our lifetimes, it would have been considered perfectly reasonable for a pope to teach about the Four Last Things. It’s really weird that it has become controversial.

Why has it become rare or controversial to speak about these four fundamental truths?

It’s become so because of whatever we want to call it: modernism, humanism, liberalism… People have stopped thinking about eternity, about the eternal truths. They stopped believing them to be true. When we see some of the discussions that are happening today over morality you can tell that people don’t really believe the eternal truths any longer. They’re not scared of hell, and they’re not necessarily particularly looking toward heaven.

In recent years, you have suffered major health challenges. Have they given you a deeper insight into the Four Last Things?

Yes, they certainly reminded me of the eternal truths. I’ve thought about the Four Last Things before, but it does bring it home to you. It reminded me that these are really important matters to think about. I hope it’s helped me and that it will help me to help others.

The first one was that I had a heart attack. I then had a heart bypass operation. The doctor comes to see you and tells you that you’ve got a chance of dying of this. They are quite straightforward about it. You can just not wake up from this operation.

The next life-threatening development was slower. I nearly starved to death. From weighing about 10 and a half stone [147 pounds], I went down to eight stone [112 pounds]. It was because of various gastrointestinal problems.

My sister’s a doctor. She took me back to her place, where I stayed for a year or so. It was the same thing called “NHS,” but it was completely different in that this one worked and the other one didn’t. The doctor took one look at me, saw the notes, and said: “Right, you need to take this drug,” which was Creon. I immediately started putting weight back on and I survived.

Those two experiences reminded me forcefully of our mortality and what I as a priest — and everyone as a Christian — should be aware of: that life is short, and eternity is long.

Let’s talk about the first of the Four Last Things: Death. Why meditate on death - isn’t it a little morbid?

We’re all going to die. That’s realistic. And it will happen within the next few decades. There’s a wonderful scene in the “Sharpe” series where an Irish priest talks to Sergeant Major Patrick Harper, who is wounded in battle. Harper asks the priest how he is, and the priest says: “Ah, you’re going to die, Pat.” There’s a prospective marriage that the priest manages to bring off there and then on the battlefield. Afterwards, this Irish sergeant gets cross because the priest says: “Right, get up and take your wife home.” Harper protests: “Father, you told me I was going to die.” And the priest says: “Pat, we’re all going to die.”

St. Thomas More, in his reflections on the Last Things, has the story of two prisoners being taken to the gallows for hanging. One’s being taken five or six miles and the other one’s just being taken a few hundred yards. It doesn’t really make much difference to them. He uses that as an illustration: we are all going to die. It’s sensible to think about our death.

What are the consequences of ignoring Death, which we seem to do even after the coronavirus pandemic and amid the vicious war in Ukraine?

The coronavirus thing was incredible. I don’t want to do down my brother priests. I’m sure there were priests who talked about the Last Things and the meaning of death. But there was a huge amount of talking about sanitizing churches and so on — anything else but preparing for death. And the Church seemed to be hugely concerned about hygiene and not focusing on the Last Things.

The one thing that we need to preach about at this time really is the Last Things and particularly the certainty of death. I think we dropped the ball on that.

St. Alphonsus Liguori wrote a meditation “On the Certainty of Death,” in which he said: “We must die: how awful is the decree! We must die. The sentence is passed: It is appointed for all men once to die.”

What happens to us once we’ve registered that?

I think it means that we can widen our horizons. St. Alphonsus is one of my favorite authors and certainly on this subject he speaks a great deal. He was trying to help ordinary people at a time of some laxity in Italian Catholic life. He tried to bring people back to a sincere practice of their faith and helped to widen their perspective.

People sometimes criticize thinking about the Last Things, saying: “Look, you’re not doing practical charity.” But if we’re thinking about the Last Things and our eternal destiny, it motivates us to do the practical charity with greater enthusiasm, greater effectiveness, and greater determination, because we know that this is going to be part of what we’re judged on. The two things go together.

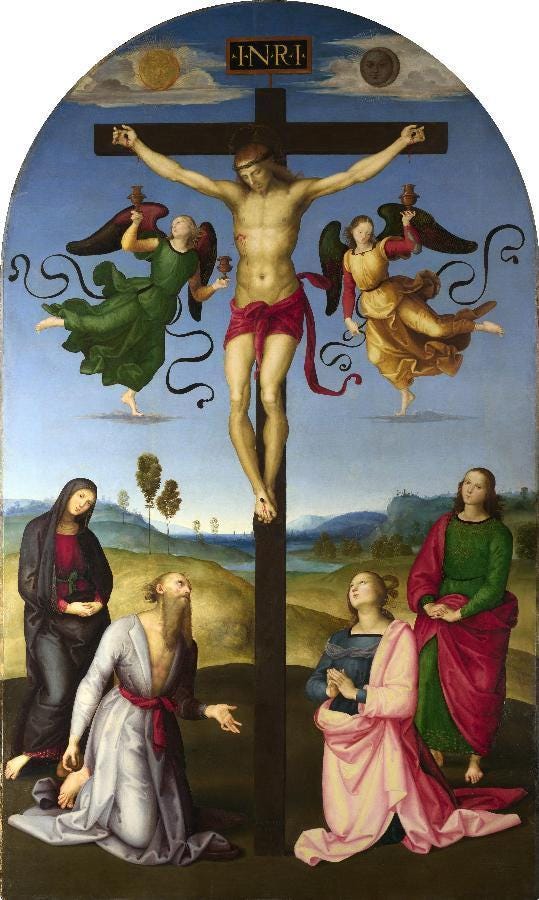

Is there a particular work of art (a book, painting, or piece of music, etc) that helps us to meditate on Death?

I would choose the crucifix. There are some beautiful examples of crucifixes. I change from one to another. At the moment, I’m particularly looking at Raphael’s Crucifixion at the National Gallery [in London]. For meditating on death, I recommend the Crucifixion, our standard image of Our Lord crucified, which is sometimes being neglected. People are displaying the “resurrex-ifix” instead of the crucifix, almost as if we’re scared to look at this fundamental truth of our faith.

Let’s turn to the second of the Four Last Things: Judgment. The Penny Catechism asks: “Will everyone be judged at death, as well as at the last day?” It answers: “Everyone will be judged at death, as well as at the last day: ‘Since men only die once, and after that comes judgment’ (Heb 9:27).”

Does this mean we will each be judged twice?

Yes. Everyone’s judged at the moment of death. So you have Dives and Lazarus: “This day” he’s gone to paradise (cf. Luke 16:22), and also Our Lord forgives the repentant thief while he’s dying on the Cross: “This day you will be with me in paradise” (Luke 23:43). At the same time, Our Lord also talks about the Last Judgment, “I was hungry, and you gave me to eat…” (Matthew 25:35). This separation of people according to their merits is carried out at that time. It was defined at the Second Council of Lyon in 1274.

There was a dispute with the pope. That’s one of the rare cases of a pope actually falling into error. The whole question was about what happens immediately after death. John XXII [pope from 1316 to 1334] was in error on that point and had to be corrected.

Why do you think that Catholics today seem uncomfortable speaking of Judgment and God as Judge?

Probably the reason some people are reluctant to speak about these things is because there’s a focus on the social work of the Church, the social influence of the Church, and social matters, rather than otherworldly things. There was criticism of Catholic spiritual writers talking too much, as people thought, about the Last Things, because they were taking us away from concern about the world and the poor.

But it’s not either-or, it’s both-and. If you’re concerned about the Last Things, then you will be concerned about having helped the poor and being able to go before Our Lord with that as something that you have done and that Our Lord will be able to judge you on. I think there’s been a false opposition between practical works of charity and concern for the Last Things.

Could it be a reaction to the perceived legalism of the Church in the past?

Yes, I think so. I mean, the perceived legalism is often false. One of the authors I’m reading at the moment is Garrigou-Lagrange. You could say he’s very technical, but we’re technical in any subject that we care about. In his more popular spiritual works, he’s easily understandable, but he’s very systematic. There’s no reason for us not to be systematic about something so important.

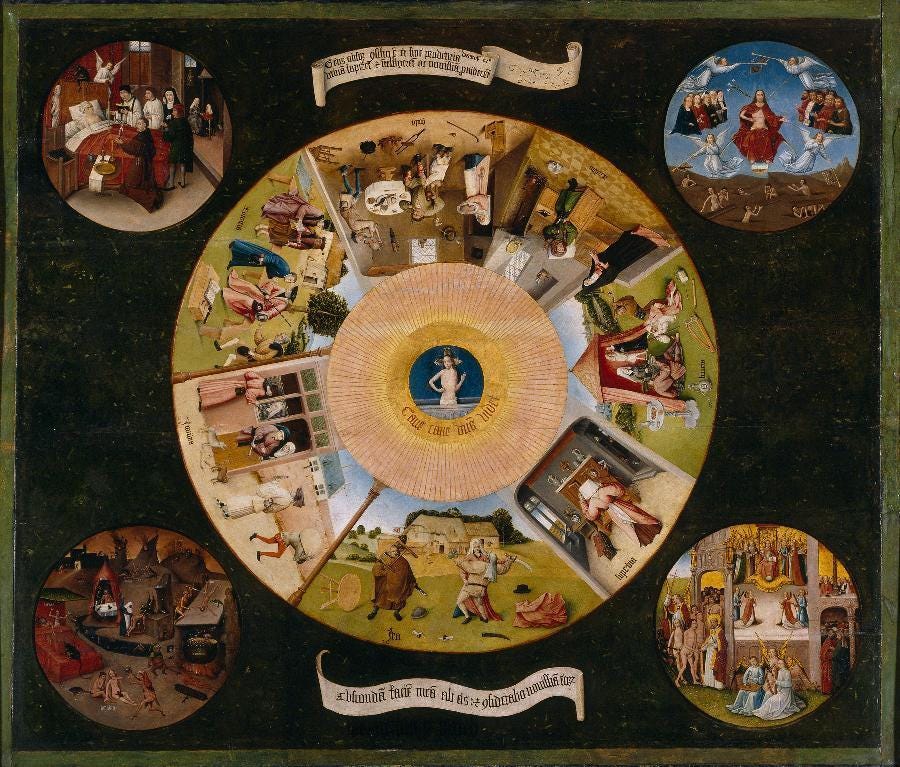

Is there a particular work of art that helps us to meditate on Judgment?

Obviously, you’ve got Michelangelo’s The Last Judgment. It was hugely controversial in its day because it’s hard to see who’s saved and who isn’t. Then you had the big controversy over the nudes, and they had to cover up all the nudes. And also Christ not being bearded: which one is Jesus, actually? So it’s a very controversial painting. And I don’t think it’s the best for us to think about the Last Judgment.

I would prefer something like Hans Memling. Many people followed his style, and he’s following something earlier, where you have a very clear distinction between the saved and the damned. You’ve got St. Michael there. You’ve got Our Lord. And it’s very clear what's going on. So I would look at Hans Memling’s triptych of the Last Judgment as an example.

📰

Let’s move on to the third of the Four Last Things: Heaven. Why do you think Heaven comes before Hell in the traditional order?

I’m not sure it always does. When Fr. Martin von Cochem writes on the Four Last Things, he puts Heaven at the end. I’m not sure it’s that important, except possibly from the point of view of public preaching, to leave people with a good motivation to change their lives and come back to Mass, and so on.

Benedict XVI once said: “All of us today are well aware that by the term ‘Heaven’ we are not referring to somewhere in the universe, to a star or such like; no. We mean something far greater and far more difficult to define with our limited human conceptions.”

So what is heaven?

Heaven is eternal and unceasing joy in the presence of God. Unfortunately, what most people have in their minds is a caricature. And I don’t necessarily just mean people’s ideas are bad. I mean that people deliberately caricature heaven and deliberately make fun of it. And that’s seen as a funny and clever thing to do. Therefore nobody even wants to think seriously about what Heaven is. I think that’s where we are at the moment in terms of the Church, which is why we really need to talk about it more coherently than we have done.

When you read the lives of the saints, many are very focused on Heaven. Yet it’s rare to meet a Christian today who talks much about it.

Would thinking more often of Heaven help us to make spiritual progress?

Yes, it would. Our spiritual lives are helped by thinking about our actual goal, as are our lives of charity, and so on. One danger people have is the self-help movement thing: a purely human approach to spirituality. We’ve been seduced into that. So you can have methods of prayer which are all about breathing, or doing a mantra, or saying a particular word.

Now, they can all be one way of helping us to get closer to God. The problem is when they’re seen as the end in itself. A genuine and good approach to meditative prayer is really important.

Is there a particular work of art that helps us to meditate on Heaven?

Rather than attempting to have pictures of heaven, which never succeed very well, it’s better to have a picture of Our Lady. We have a hugely rich corpus of art depicting Our Lady. You can choose different pictures for every day.

There was a wonderful exhibition: the Raphael exhibition at the National Gallery [in London], which had a whole room of pictures of the Madonna and Child by Raphael. An extraordinary tour de force collection.

Heaven is not something we can picture because it’s not corporeal or physical. Looking at Our Lady, she is the one that guides us to heaven. And that’s probably a good place to start in trying to focus on Heaven.

We’ve arrived at the last of the Four Last Things: Hell. What does the Church teach about Hell?

The Church teaches that if we die in the state of mortal sin, we will go to Hell or, we could say, we will be in the state of Hell, which is a state of permanent separation from God. Its nature and its horror is to be permanently separated from God, for whom we’re made.

Preachers don’t speak much of Hell these days. But its imagery is very prevalent in pop culture.

Why do you think Hell retains such a grip on the popular imagination?

Two possible reasons. One is because of an unhealthy fascination with horror and danger, and that can do people harm. Perhaps generating those images can be quite an unhealthy and morbid thing. Second, however, there’s something true there: it is possible for us to not only lose grace, but to be damned for all eternity, to be in a state of hatred of God. People don’t think in those terms, but that’s what it is that they’re trying to get at. And yes, it’s really awful, and we should fear it.

That’s the thing: we should fear losing our soul. We should recognize how wonderful it is to be in a state of grace. And that should be what we most fear losing.

Pope Francis once said that when children are taught about the Four Last Things, some might object: “Father, this frightens us.” But he said: “It is the truth. Because if you do not take care of your heart,” and “you always live far away from the Lord, perhaps there is the danger, the danger of continuing in this way, far away from the Lord for eternity. This is very bad!”

Does the Church have a duty to talk about Hell?

Yes, I think it does, because we have a duty to teach and to pass on what Our Lord taught. If we look at the Gospels, Our Lord speaks as much about Hell as he does about Heaven and mentions Hell very often in the Gospels. It’s quite wrong that many people simply miss that out.

It’s very important for us to preach about the Last Things and not ignore them. The Holy Father is quite right to mention that to the children, and I hope we hear some more from him about it.

Is there a particular work of art that helps us to meditate on Hell?

I was thinking of Mark Rothko, his blacks and grays. It represents for me something like the despair in Hell. It’s like an icon of a sort of rationally chosen despair. That would be my painting for a depiction of hell, rather than to have lots of demons or something. I like Hieronymus Bosch, but I think we need to learn something from our more recent artists.

Where are you up to with your project to write a book about the Four Last Things?

I’m reading Garrigou-Lagrange’s book on the Last Things at the moment. I’m sitting in front of the computer, listening to the text [being read], and typing notes as I go. I did a sort of structure for the book, but then realized I needed to do some more reading. I’m still quite hopeful that I can do it.

📰