Vatican lawyers deploy full court press against former auditor

Lawyers from three Vatican departments lined up in court to oppose the lawsuit for wrongful dismissal brought by Libero Milone.

Vatican lawyers argued for judges to throw out a lawsuit brought by the former auditor general in a hearing Wednesday. Lawyers for three curial departments questioned the credibility of the evidence submitted by Libero Milone in his wrongful dismissal case, and suggested further possible criminal charges against him and his former deputy.

In the first hearing of the suit, filed by the Vatican’s former chief auditor in November, lawyers for the Secretariat of State argued that the department should not be party to the case at all, while Milone’s former office said they had no record of the more than 500 pages of documentation submitted by the plaintiffs to support their case.

Milone and his former deputy, Ferruccio Panicco, filed suit Nov. 4 last year, claiming that they were forced from their roles in 2017 and unfairly threatened with criminal prosecution, because of discoveries they made while doing their work.

They have also said that after filing their suit, Vatican prosecutors informed them they were reopening a criminal case against them.

The two men are seeking more than 9 million euros in compensation for lost earnings and damages, including 3.5 million euros Panicco is seeking in material damages for the seizure of personal medical records from his Vatican office which, he says, led to a year-long delay in his diagnosis and treatment for prostate cancer, which has now progressed to a terminal stage 4.

At the time of Milone’s dismissal, Cardinal Angelo Becciu, then the sostituto (chief of staff) at the Secretariat of State, said the former senior Deloitte executive had been “spying” on the private finances of senior curial figures, including Becciu himself, and would have been prosecuted had he not resigned.

Milone has previously argued that he was forced out because his office had uncovered corruption by senior members of the curia.

“What it was,” Milone told The Pillar last year, “is that I discovered that there were cardinals putting money in their pockets, they were doing strange things.”

“Evidently, Becciu and his friends must have come across these reports because he was the pope’s chief of staff at the time, and got worried because ‘this guy’ was putting these cardinals in difficulty.”

Becciu is currently on trial in Vatican City for embezzlement, abuse of office, and other charges, all of which he denies.

In the Jan. 25 hearing, lawyers for the Secretariat of State argued that Milone had “no working relationship” with the secretariat, according to official Vatican media. The lawyers contended that Milone was under contract with the Council for the Economy — a separate Vatican department — and so the secretariat could not be sued for his dismissal.

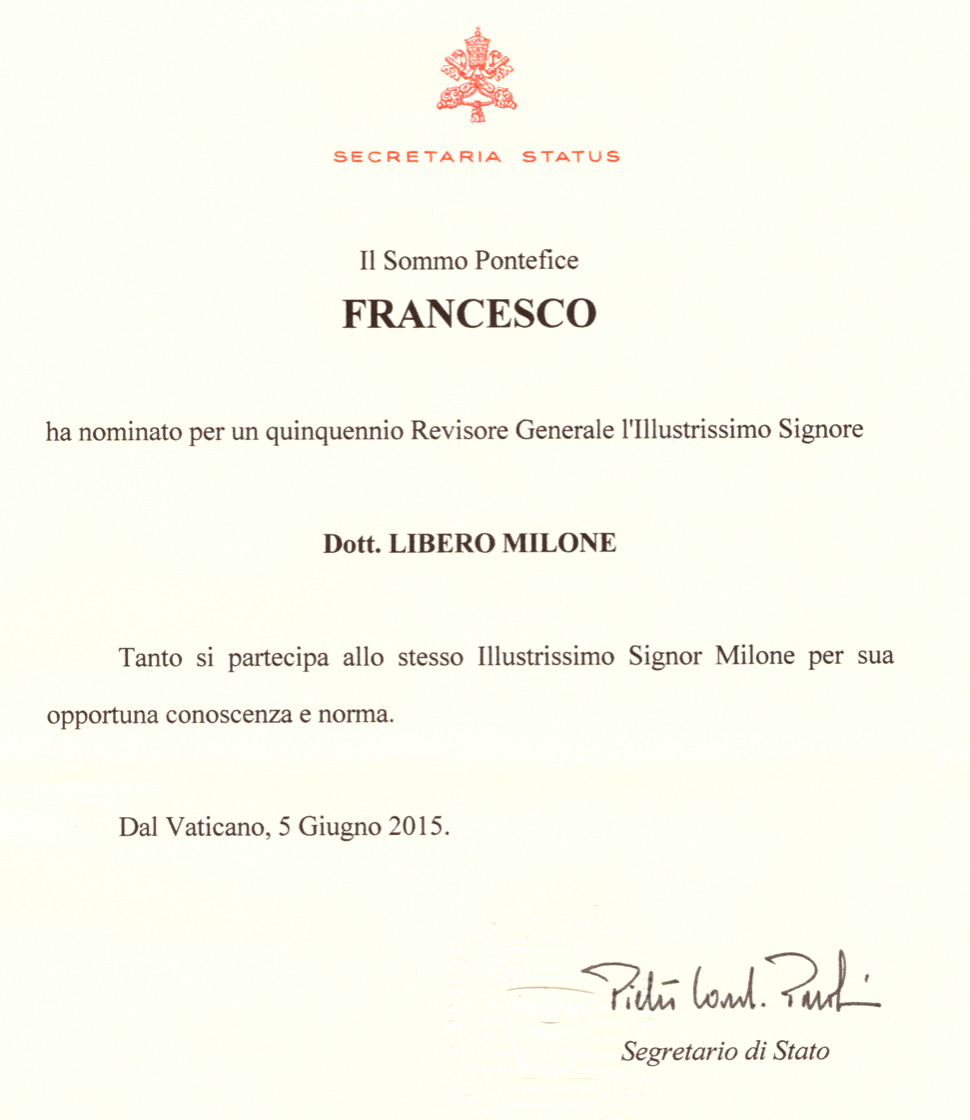

But documents obtained by The Pillar show that Milone was appointed to his former office by decree of the pope and, in line with the norms of the then-operative Vatican constitution Pastor bonus, that the decree naming Milone to the role was issued by the Secretariat of State and signed by Cardinal Pietro Parolin, as the Secretary of State.

Pastor bonus and the additions to it issued by Francis when he created the Office of the Auditor General in 2014 established Milone’s former office as specifically independent of the other financial departments of the Council for the Economy and the Secretariat for the Economy, meaning that Milone could not be considered an employee of or contractor for either, his lawyers contend.

Lawyers for Milone’s former office, which he led from 2015 to 2017, also raised objections Wednesday to the more than 500 pages of evidence deposited with the court by Milone’s legal team the previous week.

Milone has previously said that although his official files were seized by Vatican gendarmes in 2017, he still has access to records he kept at his home during his tenure as auditor general, files which he claims will exonerate him from the accusation of spying and demonstrate a culture of financial corruption at the Vatican, including among senior cardinals and curial officials.

Those files, deposited with the court on Jan. 18, were the subject of several objections during the hearing Wednesday. Lawyers for the Office of the Auditor General said that no official record could be found of the files, which they also claimed they had not had time to study in their entirety.

“It emerged that of the 39 documents filed, only a few belong to and can be found in the Office of the Auditor General,” the court was told. “There is a well-founded hypothesis that the documentation is not authentic,” lawyers for the Office of the Auditor General said, while urging the judges to dismiss the case and suggesting that Vatican prosecutors should consider bringing charges against Milone.

Milone’s lawyer argued that the objections to the documents were “a tempest in a teacup” and meant as a legal delaying tactic.

All three Vatican departments involved in the trial already had access to the documents long before they were deposited, Milone’s lawyer argued, pointing out that the former auditor had given them to Cardinal Parolin himself in meetings before the suit was filed, that his successor as auditor general was well acquainted with them from their own time working together, and that the Promoter of Justice had seized copies from his Vatican office in 2017.

In previous statements to the media, Milone and Panicco have both repeatedly said that, at the time of their ouster, documentation kept in their offices were impounded by Vatican gendarmes, removed from the auditor’s department, and never returned — including Panicco’s personal medical records.

Milone has previously said the documents he submitted prove personal acts of embezzlement by cardinals, and the use of Vatican institutions, like the city state’s governing apparatus and the Bambino Jesu hospital, for money laundering. Milone has said he does not intend to “name names” or make his evidence public unless he is denied the chance to clear his name in Vatican court.

📰

Also present in court Wednesday was Alessandro Diddi, the Promoter of Justice, or chief public prosecutor, for the Vatican. Diddi told the court his office had made itself party to the case because it touched matters of “public interest”, including the alleged abuse of office by public officials — both those accused of unjustly forcing Milone and Panicco from office, and the plaintiffs themselves whom, Diddi confirmed, had been under renewed criminal investigation for several months.

In light of the documents deposited by Milone’s legal team, Diddi said his office was also now considering charges of theft of official documents.

Milone has previously said that the Vatican criminal investigation into his time in office was reopened in retaliation for his decision to file a claim for wrongful dismissal. At the time of his departure from office, Milone has said, Cardinal Becciu and senior officers from the Vatican gendarmes detained, berated, and intimidated both him and his former deputy for hours to force their resignations.

At that point, the men were made aware of a months-long investigation into their department. Milone has previously said that Domenico Giani, former head of the Vatican City police, who authorized that investigation, played a central role in his departure from the Vatican.

Milone charges that Giani engaged in his own financial misconduct, and that when Milone discovered it, the police agent formally accused him of illicit spying. The former auditor also recalls finding that his Vatican offices had been bugged and his office’s computers hacked, and claims that while he made several complaints to Vatican police, the security breach was never investigated.

Speaking to The Pillar in November, Milone noted that Giani “had a reason to get me out,” because he had uncovered evidence of corruption in the Vatican police force.

Giani was himself forced to resign in 2019 as a result of leaks from his department related to a different investigation into Vatican financial affairs.

In court on Wednesday, Diddi said that if members of the Vatican police force had worked to drive Milone and Panicco from office, these would be acts by individuals and not make the Vatican state liable in the lawsuit.

“If this is true, it is a unilateral action by a judicial police officer,” Diddi said. “How many times does it happen that in Italy [officers of] the Carabinieri carry out illegal activities but the president of the Republic is not responsible for this.”

Also during the hearing Wednesday, Diddi joined lawyers for both the Secretariat of State and the Office of the Auditor General to move that the entire suit be dismissed because the five-year statute of limitations for Milone to bring a legal action had expired.

Milone has previously said he has spent the years since his 2017 dismissal petitioning Cardinal Parolin to pay him and Panicco the balance of their Vatican contracts, and to have the Holy See publicly clear their names to allow them to find other work.

Those meetings, Milone said previously, were always friendly but fruitless, leading him to give notice of his intent to sue in February last year — within the time frame allowed by law — but was further persuaded to delay when told a settlement could be possible. In court, Milone’s lawyer argued that the documents deposited showed “the repeated interruption of the course of each statute of limitations” by the Vatican as Milone and Panicco sought an out-of-court settlement for their claims.

During the hearing Wednesday, Milone’s lawyer also petitioned the judges for a postponement of proceedings, since the Vatican court has yet to admit his principal legal counsel to appear on his behalf. That motion was rejected by the judges.

Milone is currently represented by Vatican-approved attorney Giovanni Merla but has repeatedly requested that he be allowed to nominate a second lawyer to represent him as well. Such arrangements are standard practice in Vatican City, and authorization for Italian lawyers to argue in Vatican courts is normally given as a matter of course.

The case adjourned Wednesday with no date set for a further hearing. Chief judge Giuseppe Pignatone told the court that the bench would study the files submitted by Milone “with the utmost attention” before issuing a decision on when, how, and if the case will proceed.