USCCB debate on priest formation plan was part of broader pushback

After the bishops passed a 'basic plan' for ongoing priest formation, will priests read it?

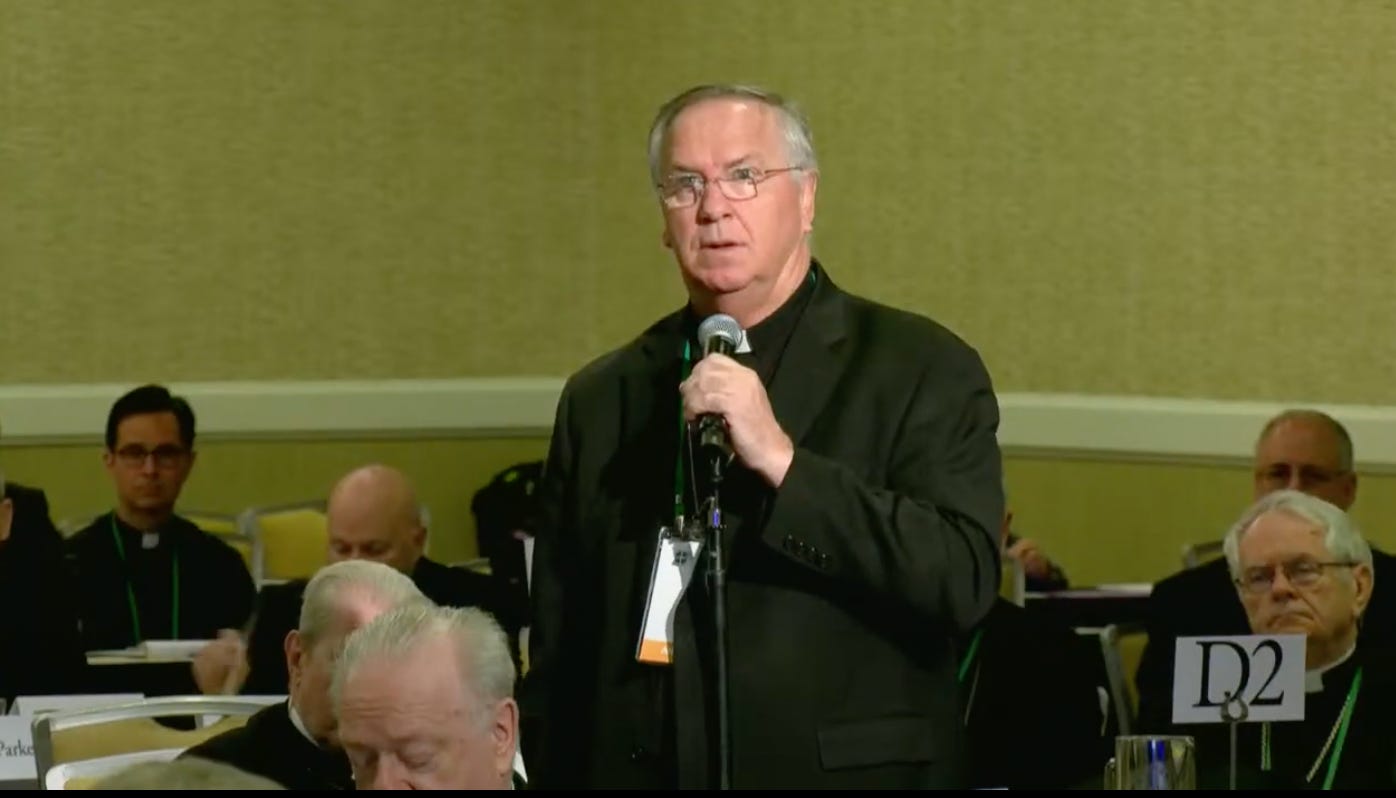

Before the U.S. bishops passed on Friday a new plan for priestly formation in the country, a handful of prelates stood to oppose the use of language around priestly identity contained in the text.