Pillar subscribers can listen to Ed read this Pillar Post here: The Pillar TL;DR

Happy Friday friends,

It is the feast of St. Valentine, of course — widely marked throughout the world as just “Valentine’s Day.”

Out of all of the roided-out global consumer holidays with an historic toehold in Christianity that pockmark our calendars and bank accounts, I have to say I find this one the most curious.

In this country, the day is, depending on what building you’re standing in, either a twee bonanza of affection or a carnival of raunch. The juxtaposition gives me constant whiplash.

It’s jarring that, for example, school kids swap innocent, decidedly cute pink and red cards and candies while some of the stores in the mall are decked out like Parisian boudoirs. I suppose it all comes from our culture’s inability, in language or in thought, to distinguish properly between the concepts of eros and agape. Blame the education system for scrubbing classics from the curriculum, I guess.

For myself, I have never really known what to make of the day.

As a child in the late 1980s, I remember it as an occasion of real, if indefinite, anxiety as I hung out my little post box on the end of my desk in the enforced expectation I might receive a minimal number of cards to avoid either pity or ridicule.

And the decision of to whom I should send token greetings of superficial affection, and how personalized they should be, preyed upon my young mind — I was no more socially outgoing then than I am now.

I recall the momentary elation when, in Mrs. Shaffer’s first-grade class, I received effusive thanks from one of my classmates, Elaine Moran. I was pleased that I had, as that Japanese cleaning lady on Netflix puts it, “sparked joy.” But it soon gave way to self-doubt — had I incurred some kind of ongoing social obligation to Elaine? Could I keep meeting the impossibly high bar of creativity and humor I had set for myself with my construction-paper robot?

Nearly 40 years later I can’t say I approach the day with much less concern. If anything, the stakes are higher. My own inamorata, being of robust English sensibilities, disdains the secularized nonsense of Valentines Day, seeing it as an exercise in vulgarity and a rip off for all concerned.

I don’t disagree. But, of course, there’s the rub.

To do nothing to mark the day is to push a lot of domestic chips into the middle of the table in a bet she will hold to her principles and not make some token gesture of marital devotion of her own. On the other hand, to present her with flowers and a card would risk her (reasonable) irritation at my buying into the con and paying over the odds for seasonal gas station floristry.

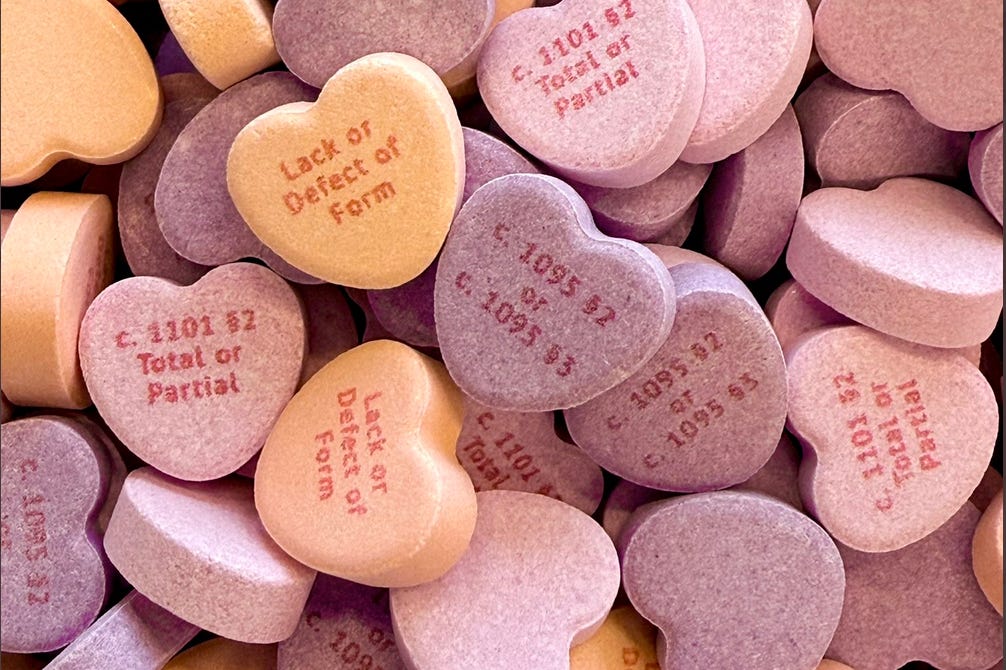

The trick is to make some small gesture, neither trivial nor over the top, at once affectionate but defensibly ironic, to cover your bases. Like candy hearts with grounds for annulment on them.

Or writing a contrived preamble to a newsletter, as a cover to tell your wife you love her.

Something like that, anyway.

Here’s the news.

The News

Pope Francis this week released a “fraternal letter” to the bishops of the United States on “the major crisis that is taking place in the United States with the initiation of a program of mass deportations.”

The letter not only had some strongly worded critiques of the Trump administration policies, but also what looked like a direct riposte to Vice-President JD Vance’s recent comments on twitter.com about the ordo amoris.

You can read our summary of all the text and context here.

—

One of the more controversial policies announced by the administration as part of its agenda to deport illegal immigrants is a deal struck with Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele to house U.S. deportees with violent criminal records.

The prison set to house American detainees is CECOT, the Terrorism Confinement Center, a large, recently built, and controversial high-security prison, built to house up to 40,000 inmates.

—

Sticking with immigration for one more moment, the Church in Germany is fracturing further in the fallout of a controversial immigration vote in parliament last month, and ahead of snap federal elections.

The issue of immigration looks likely to redraw the country’s political map and the major parties are in turmoil about possible (likely, even) major gains being made by the AfD, the right-wing nativist party.

Of course, this isn't coming out of nowhere. The country has struggled (and that’s putting it mildly) to assimilate the million Syrian migrants and refugees who entered Germany in 2015, and a spate of mass-casualty attacks perpetrated by immigrants in recent months is taking its toll on the country’s centrist political settlement.

Alongside this, German Catholic groups are no less at odds over how to respond than the major political parties — from the bishops’ conference, to the influential Central Committee of German Catholics to the Catholic German Women’s Association.

So what’s happening, and what’s going to happen next? Luke Coppen looks closer right here.

—

A prominent Croatian archbishop is at the center of a growing storm over his handling of a clerical abuse case.

The chain of events is being described in the country as “the greatest scandal in the history of the Church in Croatia.”

So, how exactly did Križić handle the case? How has he responded to the criticisms? And what’s likely to happen next?

—

Pope Francis established the Diocese of Mindat in Burma last month, designating the Church of the Most Sacred Heart of Jesus as its new cathedral. Twelve days later, bombs struck the building, leaving it unusable.

The bombing was reported Feb. 10 by Agenzia Fides, the Pontifical Mission Societies’ information service. An accompanying photograph showed a hole ripped in the church’s roof, surrounded by rubble and masonry.

Bombs have repeatedly hit Catholic churches in Burma/Myanmar since the Southeast Asian country plunged into civil war in 2021.

So what happened, and why do the bombs keep falling churches? We bring you the whole story here.

Hot takes

Predictably, the pope’s letter has generated a lot of reactions and headlines. The “hot takes” have been coming thick and fast.

Plenty of people have cheered the pope’s pointed criticism of the Trump administration, and his barely veiled rebuke to the VP. Others, of course, have rounded on Francis, insisting he is neither correct in his assessment of the issue nor qualified to give it in the first place.

For myself, I see nothing wrong in principle with the pope weighing in on any matter of international political import he sees fit to, or correcting prominent Catholic politicians offering their interpretations of Church teaching.

But I was left disappointed at the substance of Francis’ letter.

A plain text reading of some sections of the letter seemed to me to at least lend themselves to the interpretation that the pope was sort-of-kind-of saying any limits on immigration are immoral (maybe?) and I don’t see how that helps anyone’s cause here.

And his admonition that we all meditate on the parable of the Good Samaritan could, I’d submit, have been a little more explicit in the lessons he thinks we should draw from it.

Moreover, if the pope does choose to weigh in with a formal letter in response to a Catholic vice-president on the issue of immigration, it’s pretty hard not to ask why he didn’t feel that our previous Catholic president didn’t merit a similarly textual response on abortion.

The impression is hard to escape that only Catholics of some political persuasions and some issues in American political life merit the full papal attention — and that’s an impression some people at least are going to run with.

I worry Francis’ letter is going to be mostly used as ammo by the fringe but growing sector of American Catholicism, often clustered around figures like the excommunicated former nuncio Archbishop Viganò, who overtly insist that populist politics can and should trump the Church hierarchy for their allegiance.

If not everyone thinks that’s a problem, well, I do.

In short, the letter seems to me much more likely to fuel “political Catholicism” than to advance a more Catholic politics. Frankly, I’d hoped for more, and better.

You can read the whole analysis here.

JFK

Who killed JFK? The conspiracy theories around this question are probably one of the most interesting, absurd, entertaining, bizarre, earnest, compelling, and often tasteless cul-de-sacs of American pop culture and public life.

From what I understand of it — and I’ve read a few books, nothing more — the evidence against Lee Harvey Oswald stacks up pretty high and wide. And I buy it. Pretty much.

And yet.

And yet how does a social weirdo conceive of such a plot and seemingly luck into the ability to pull it off? And what are the odds of even a crack shot making those hits on the small and moving target of the president from that distance through intermittent tree cover?

And if not Oswald, or if not him alone — as apparently some two-thirds of Americans believe — then who did kill Kennedy? The Chicago Outfit? The CIA? LBJ? The military-industrial complex? All of them?

My personal pet theory is that Oswald shot Kennedy, but the Russians were in on it, and the state had to move heaven and earth to bury the fact and avoid thermonuclear war. But no one can say for sure because, despite 60 years, the Warren Commission Report, and the JFK Records Act, thousands of government files about it all are still under wraps, for the moment.

President Donald Trump has ordered (as it should be noted other presidents, including Joe Biden, have done in the past) the declassification and release of the JFK files. Apparently, the FBI says they have “found” some 2,400 such documents and are preparing a report for the president.

What’s in them is anyone’s guess, though I suspect not much — at least nothing conclusively contra the current historical narrative.

While I am just out there enough to admit the possibility of a massive institutional conspiracy to kill the president, my incredulity kicks in at the idea that they documented the fact and neatly filed the evidence.

On the assumption that when the new docs drop we’ll either learn nothing new, or something that closes the door harder on the conspiracy theories, I think it’s worth thinking about what makes conspiracy theorizing the JFK assassination so compelling in the first place.

Oliver Stone’s masterpiece film treatment of the case, which is as riveting as it is bonkers, invites us to consider the question “through the looking glass, people, where black is white and white is black,” in which nothing makes sense and no assumption is reasonable.

That’s kind of the whole riddle of America in the 1960s, maybe the most colorful and contradictory decade in our history.

It was a time of economic boom, desegregation, peaceful marches, riots, disastrous military engagements, heroic Cold War diplomacy, political icons, multiple assassinations, hippy nonsense and NASA triumphs.

In 10 years, our country simultaneously faced down the Soviet Union at its apex over Cuba, began an earnest reckoning with our own national shame of racism, and landed on the moon, all while shooting the people who led us to those achievements and kicking violently against the progress we made along the way.

How is it possible that in such a time, with so much riding on a razor, poised between international armageddon and domestic anarchy, we seamlessly survived the assassination of a head of state? It’s frankly incredible. We can’t believe our own history, indeed we couldn’t believe it as it was being lived, and we’ve sublimated that incredulity at our national survival into JFK’s death.

Most of us want to think there was something more to who killed JFK, because, I think, most of us find the answer we have — a lone and lonely gunman — unfit for the times, and unbefitting the significance of the moment.

Stone’s fictional theory, or one of them, is that everyone was in on it. From the White House to the national press, to the generals of the military, the captains of industry and capos of the criminal underworld, every strata of American leadership conspired to kill Kennedy and calmly condition the country to just keep it together and go along with it.

The alternative is, I would argue, more arresting and even more unfathomable by today’s standards: that we had a wellspring of collective national resilience and communal sense of self deep enough to preserve our society intact, when by all rights it should have burst into flames.

Maybe that’s the truth of it. Or maybe it’s the more noble fiction — the national mythology we should be proudly buying into.

Either way though, it couldn’t give us John Candy’s career-best performance.

See you next week,

Ed. Condon

Editor

The Pillar

"And what are the odds of even a crack shot making those hits on the small and moving target of the president from that distance through intermittent tree cover?"

About 96%

Years ago my Knights of Columbus council's right-to-life coordinator was a retired FBI agent. He had just joined the Bureau when the assassination occurred, and since he was stationed in New Orleans he got the job of going through the entire library looking for books Oswald had read. He found 4, 2 on shooting and 2 novels on political assassinations.

But the most fascinating story, to me, was his account of how the U.S. built a re-enactment of the shooting scene at a military base, with a limo filled with dummies drawn along a car wash style track. One hundred riflemen were drawn at random from various units, put in a tower that simulated Oswald's window, and told to kill the president. Ninety-six succeeded.

He didn't mention any simulation of the tree cover, but given that number it seems a trivial issue.

A Valentines Day flame out, a Pontiff/VP knee scraping schoolyard match, a thoughtful riff on the JFK assassination, and John Candy all in one post??? Extend my subscription for eternity please, let me know what the cost is for that category, I don't see it as a renewal option.