Happy Friday friends,

Last night, I made it to the movies to see the new Napoleon biopic. I’ll spare you a full amateur film review, though I thought it was by no means on a par with Ridley Scott’s great works but still pretty good.

The French news magazine Le Point called the film “very anti-French and very pro-British.” I would say it definitely lived up to that promising review.

One of the most interesting figures in Napoleonic history is Tsar Alexander I, though he’s given little screen time in the film. On that score, for those of you who delight in good biography, I recommend without reservation the French historian Marie-Pierre Rey’s work “Alexander I: The Tsar Who Defeated Napoleon.”

It is a great read and includes the assertion, with some considerable historical evidence, that before the Tsar’s “death” in 1825 (to explain the scare quotes you’ll have to read the book) Alexander was actively engaged in a project to forcibly reunite the Russian Orthodox Church into communion with Rome under the authority of the pope.

How that would have redrawn the ecclesiastical and political map of Europe, and reshaped the coming centuries, we can but imagine. It’s a great read.

Now, enough history, here’s the news.

The News

This Sunday opens the season of Advent which, by count of days, is as short as it can possibly be this year, since Christmas falls on the Monday following the fourth Sunday.

One of the canonical questions we get asked a lot is what the Mass obligations are for Catholics when a major feast like Christmas falls right after a Sunday.

Do you have to go to Mass twice (yes, you do), and how does it all work with midnight Masses and anticipatory liturgies the night before?

Of course, the most important thing is to actually go to Mass, and to think about not as an obligation, but as the greatest gift the Church has received and has to offer us — Christ truly present, here, for us.

As a wise man once noted, that’s what Christmas is all about, Charlie Brown.

—

Candidates for the priesthood in the chief diocese of the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church will have to sign a written pledge to celebrate and endorse the revised Eucharistic liturgy to be ordained.

Anyone who has been reading The Pillar’s coverage for a while now knows something about the roiling liturgical dispute in the Syro-Malabar Church, which has seen riots, Vatican interventions, and threats of wholesale excommunications.

As I’ve said before, this is not some side issue in a far-away place. This is a crisis at the heart of the second-largest Eastern Catholic Church.

How it develops and eventually (one hopes) resolves matters a great deal to the universal Church.

—

This is not an easy time to be a Christian in Russia, between the Russian Orthodox Church’s open support for President Putin’s war on Ukraine and a clampdown on internal political dissent, according to a specialist researcher at the organization Russia Cristiana.

Speaking to The Pillar’s Filipe D’Avillez this week, Marta Dell’Asta said that in the Soviet era, “we knew that there was an enemy, Communism, and we tried to help all the dissidents.” But now, she says, “the involvement of the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) with the government has blocked the process of ecclesial freedom that began in the 1990s.”

The impression from the outside looking in at Russian Christianity can be that it is foursquare behind the Putin regime. Not so, Dell’Asta said. Many Christians know there is a problem.

“As a matter of fact, many priests have been dismissed from the ROC, suspended, because they didn't pray for victory, as they were told, but for peace. This is a tragedy for the priest and his family, but also for his flock, which often loses trust in the institutional Church. So now we are trying to sustain them, and that is a new challenge for us.”

So how do you support Christianity in Putin’s Russia? Read the whole conversation here.

—

The Pillar broke the news this week that back in September, a Massachusetts priest charged with stealing more than $100,000 made a plea bargain with prosecutors, and was granted probation on condition of his “voluntary laicization.”

The diocese told The Pillar that Fr. Tomaz Gorny is facing some kind of “canonical process,” but said it was not able to answer any questions about it, or clarify whether he is seeking laicization, in accordance with his probation documents.

Canon law, as it happens, does not prohibit a diocese from providing public information during the course of canonical penal or administrative processes. And in 2020, Springfield’s Bishop William Byrne said he would prioritize “transparency” in diocesan handling of clerical misconduct cases.

“Transparency and communication are demanded of us, and this will be my priority,” the bishop said then, as many bishops did in the aftermath of the McCarrick scandal.

Making those commitments a reality, though, remains a work in progress. At best.

—

Meanwhile, in the Archdiocese of Milwaukee, a senior-ranking priest appears to have been cohabiting for years with a man whom he hired to teach religion at his parish school.

But in announcing the hire, he did not mention that he had been sharing a condo with the man for decades. Or that the new hire had made a series of posts on social media documenting their life together as a “couple” at home, on various getaways, and at Pride events and gay bars in Milwaukee and further afield.

The archdiocese confirmed to The Pillar that earlier this year “an anonymous person provided information to the vicar for clergy regarding Fr. Payne” to that effect, and that it had been “followed up.”

“We have … spoken with Fr. Payne about the necessity for clergy to live a lifestyle that avoids scandal and is faithful to their promises of ordination,” the archdiocese told us.

“He has given assurances that he is faithful to his priestly vows and we have given him the opportunity to correct any perception that his lifestyle is inconsistent with the life of a priest.”

There, so far as the archdiocese is concerned, the matter shall rest.

Of course, it was not long ago that Pope Francis made a special point to remind bishops that “In the past, great damage was done by a failure to appreciate the close relationship existing in the Church between the exercise of charity and recourse — where circumstances and justice so require — to disciplinary sanctions.”

When Francis issued a new penal code for the universal Church in 2021, he wrote that “this manner of thinking — as we have learned from experience — risks leading to tolerating immoral conduct, for which mere exhortations or suggestions are insufficient remedies.”

“Negligence on the part of a bishop in resorting to the penal system is a sign that he has failed to carry out his duties honestly and faithfully,” said Francis.

It’s a lesson from the pope which, it seems, has yet to be appreciated by all bishops.

From class to Mass, the University of Dallas student body is a tightly knit community of thinkers seeking a truly meaningful life. United around our nationally recognized Core Curriculum, students’ experiences are enlivened by our transformative study abroad program, numerous student activities and organizations, and faithful Catholic identity. Come pursue a life well-lived. Find out more about student life at UD at udallas.edu/pillar.

Selective subsidiarity

Of course, there is a wider ongoing discussion about how faithfully Pope Francis himself applies his own canonical legislation, especially with regards to problem bishops.

In an interview this week, one of the Vatican’s most senior canon lawyers fielded questions about the recent dismissal of Bishop Joseph Strickland from the Diocese of Tyler, and also about the problem presented by the German bishops in pursuit of their “synodal way” program.

As I wrote in an analysis this week, I’m not so sure.

It was Francis who, in 2016, issued new canonical legislation, making it a removable offense for bishops to cause “grave harm to others, either to physical persons or to the community as a whole. The harm may be physical, moral, spiritual or through the use of patrimony.”

Francis also created a clear, and I think important, legal process for initiating the removal of bishops who cause such harm while respecting the rule of law and their right to mount a legal defense of themselves.

What Francis did was, in essence, to criminalize bishops being bad at their jobs. It was a dramatic reform and heralded a new era of centralization in the exercise of papal power — I wrote as much at the time. But Francis seems increasingly to have kept his criteria for episcopal removal, but quietly dropped his own process to ensure justice in the application.

That, I would argue, is concerning on its own. But more concerning is that this new willingness to remove bishops from office seems to be very selectively applied.

Witness the German bishops who routinely defy Vatican instructions and openly dissent from Church teaching — an arguably obvious case of challenging papal authority and doing spiritual harm to local dioceses.

The conclusion to be drawn, it seems to me, is we have a very selective kind of subsidiarity being practiced when it comes to problem bishops, rather than a “grand decentralization.”

You can read my analysis here and make up your own mind.

What I would say though is that if Pope Francis remains committed to apparently arbitrary application of his own disciplinary norms, it can hardly be a surprise if bishops in their own dioceses do the same.

In that sense, we’re right back where we were in the scandals of recent decades — and where, we were all told, we’d never be again.

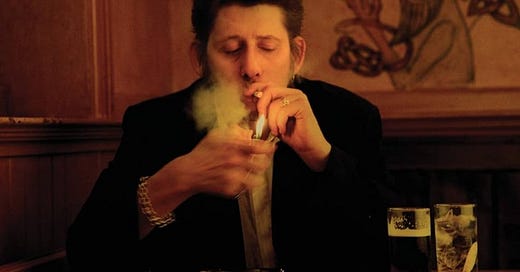

The Legend of Shane MacGowan

Yesterday Shane MacGowan, lead singer of the Pogues, died at age 65.

He was, in every sense, a living legend of Irish music — so much so that many people, sincerely, expressed shock that he was actually still alive.

Most people, at least in this country, know him best for his fiercely melancholic Christmas ballad Fairytale of New York, though the Pogues albums “Rum, Sodomy & the Lash” and “If I Should Fall from Grace with God” firmly fixed MacGowan as the living conduit of a musical tradition all too often dismissed as a postcard anachronism, created to appeal to tourists.

There was nothing contrived, though, about MacGowan, who was the living embodiment of the distinctly Irish contradiction of “fierce melancholy.” An incredibly gifted writer and poet, he wrote, performed — and lived — with a kind of burning urgency that seemed at once self-consuming and yet in him, rather than from him.

It would be easy to dismiss the riotous drinker and singer, whose punk-inflected incarnation of Irish ballardry seemed stoked with some terrible ferocity, as just an eloquently wounded product of a now nearly vanished Irish society. But what marked him out, to me, was that he was driven by something from within, not without.

Born on Christmas Day in 1957 to Irish parents in England, he spent his early life back in Ireland, living in a family cottage in rural Tipperary, where the children slept three to a bed, there was no running water, and the family cooked on an open fire.

According to his parents, music and storytelling were the focus of their family life in those days.

“It was basic and beautiful,” he said of his childhood. “It was the end of an era that I just happened to catch. And I’m glad I caught it, you know?”

By the time he was a teenager, the MacGowans were back in England, where his father found work, and he was winning essay competitions with writing that confounded his teachers while struggling to fit in, as a rural Irish boy, among the well-heeled students at the top private school to which he’d won a scholarship but from which he was expelled after two years.

With such a childhood, mixing poverty and displacement and isolation, it would be natural for MacGowan to rage against his own background — as many people do in similar circumstances. Yet he loved who he was and where he came from.

“I didn’t have this sort of [attitude] of someone who’s brought up in Ireland until they’re 20 or something and is always cursing the Church and the Christian Brothers and the small-mindedness and the gossiping and the sadism and the brutality and all the bad things you can say about our society.”

“All I ever had were happy times,” is how MacGowan described his childhood in Ireland.

This deep understanding and love for his own history and where he came from, which John Paul II also wrote about in “Memory and Identity,” suffused MacGowan’s music.

But even as he became a kind of living totem in his home country it was clear he loathed the spotlight, writhed during interviews, and fought, often unsuccessfully, to balance his natural reticence with the convulsive need to make his music.

It drove him to at times terrible self-destruction, but the defiance and desperation of his singing seemed always directed back within himself. And it was a great comfort to read his family’s announcement that he’d died with the last rites imparted.

He was a man for whom the words of Jim Harrison, another great poet, seemed to be written:

Some people hear their own inner voices with great clearness and they live by what they hear. Such people become crazy, or they become legend.

Rest in peace, Shane.

See you next week,

Ed. Condon

Editor

The Pillar

Beautiful tribute to Shane. Thank you, Ed.

Can’t say I care too much for the music but I’m from an older generation. On the subject of priest stealing from the faithful and cohabiting with men or women I have this to say:

1- get them out of the parish and take away their priestly rights.

2- publicly correct them

3- they are a scandal to the faithful especially the youth

As for the popes actions toward Cardinal Burke and Bishop Strickland, I am very disappointed in his decision. The German Bishops are another scandal and I can only imagine the pope is allowing such behavior to prevent a worse scandal. I am very concerned about the state of the Church but Jesus isn’t surprised. God has allowed this for a good reason.