The ‘solidarity of simplicity’ – Nigerian seminary rector forms priests for global ministry

How a seminary rector in a violent region of Nigeria aims to form men for missionary priestly ministry.

Fr. Mark Nzukwein is the rector of St. Augustine's Major Seminary Jos, Nigeria, in the northern region of the country, close to the epicenter of Boko Haram and other Islamist militant activity.

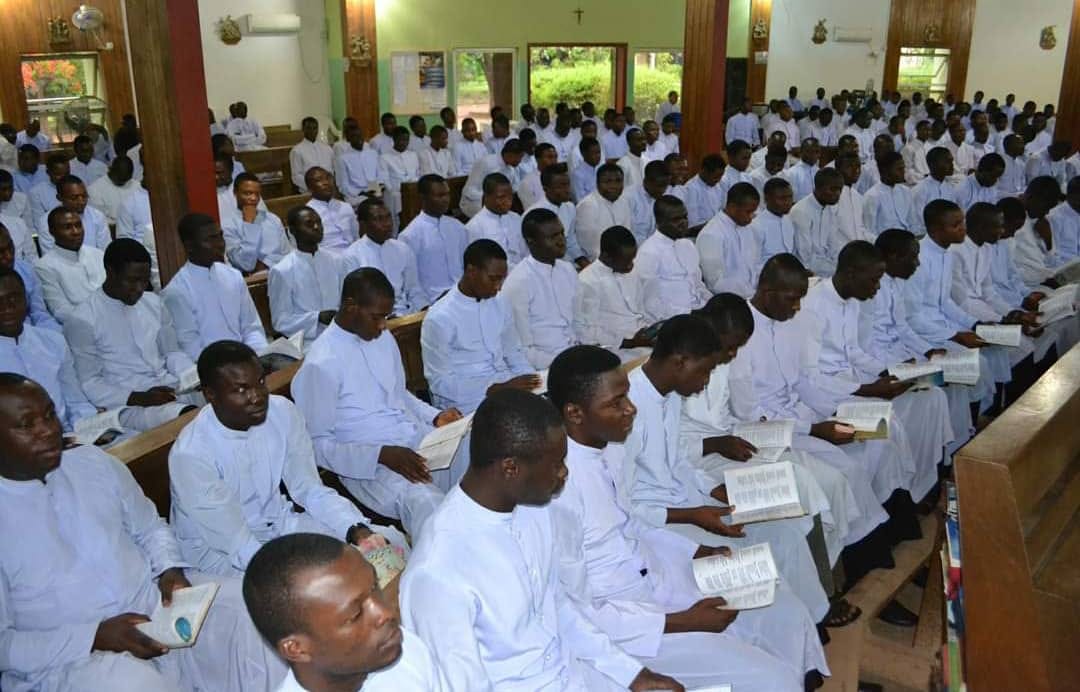

St. Augustine's is the oldest major seminary in Nigeria's northern region; it is home to 356 seminarians, 19 resident formators, 2 non-resident full-time formator…