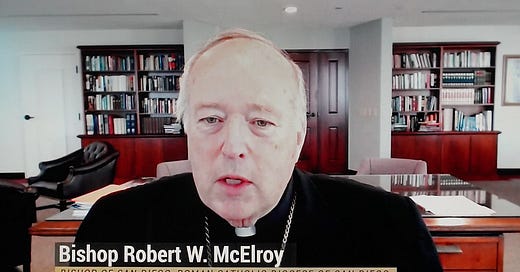

Papal advisor Fr. Antonio Spadaro said Sunday morning that the pope’s appointment of San Diego’s Bishop Robert McElroy as a member of the College of Cardinals is “a strong and clear message for the Church in the United States.”

The appointment came as a surprise, apparently even to McElroy, who said in a May 29 statement that he was “stunned” by the papal nod.

Indeed, the cardinal-elect is not the metropolitan of a major archiepiscopal see, nor the prefect of a Vatican dicastery. Francis has previously appointed as cardinals the bishops of smaller sees, but every U.S. bishop to whom he has previously given a red hat has been an archbishop.

And given that a growing number of American Catholics are Hispanic, many Vatican-watchers expected the next U.S. cardinal would also be Latino, even if it was not Los Angeles’ Archbishop Jose Gomez, whom the pope has now passed over several times.

After McElroy, 68, is formally elevated to the cardinals’ college in August, he will be in an unusual situation: his metropolitan archbishop leads the largest diocese in the United States but is not a cardinal, while Cardinal McElroy will be head of only the third-largest dioceses in the Los Angeles metropolitan province.

The pope is not in the habit of explaining why he elevates bishops to the College of Cardinals. But if Spadaro is right, and McElroy’s appointment is meant to be a “strong and clear message,” at least some Catholics are asking what Pope Francis wants to convey.

While the labels and language of political sociology are not especially helpful in discussing the Church, McElroy is the most outspoken among those U.S. bishops whose views can be roughly characterized as “progressive” — at least in the context of the American episcopate.

The bishop has made it a point to speak in favor of the ordination of women to the diaconate, to suggest that sacramental discipline - like this month’s prohibition of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi from the Eucharist - “weaponizes the Eucharist,” and to insist that: “It is not Catholic teaching that abortion is the preeminent issue that we face in the world of Catholic social teaching,”

In 2019, McElroy also told the bishops their acknowledgement of abortion as a preeminent priority — the killing of nearly a million unborn children each year — was “discordant with the pope’s teaching, if not inconsistent.”

The cardinal-elect is not aligned with most American bishops on most of those issues, and has seemed entirely undisturbed by that. In fact, McElroy has more than once risen among the U.S. bishops to offer himself as a kind of interpreter of Pope Francis — usually to the frustration of other bishops in the room, who have suggested that they too are capable of understanding the pontiff.

Of course, Pope Francis is not likely especially attentive to the debate at the assemblies of the U.S. bishops’ conference.

But if McElroy’s appointment is intended to send a message, the most obvious one is that the pontiff favors McElroy’s theological vision and pastoral priorities for the Church in the U.S.

If the majority of American bishops have a different sense of how they’re called to lead the Church, it seems reasonable to take McElroy’s appointment as a reproach.

But some bishops told The Pillar today that if the appointment of McElroy was intended as that kind of signal, they would better understand a more direct, systematic, definitive correction from the pontiff, rather than a sort of reproof by implication.

And there are questions about how McElroy’s style will contribute to the pope’s other goals. Leaving the doctrinal orthodoxy of his theology to one side, bishops have described the San Diego bishop as a firebrand or as combative, even pugilistic, in debates with his brother bishops.

While the pope has encouraged episcopal unity, and urged the American bishops especially to more charitable fraternity, it’s not clear those goals are immediately served by the appointment as cardinal of an outlier whose mode of engagement has not proven effective at forging consensus.

In fact, some bishops told The Pillar Sunday the appointment felt like a repudiation of their own efforts to forge unity — including on the 2021 Eucharistic document, on which they eventually achieved considerable consensus, after months of sharp debate.

In reality, the appointment of McElroy as a cardinal is likely to inflame division among the U.S. bishops.

As cardinals close to the pontiff, McElroy, along with Cardinals Blase Cupich and Joseph Tobin will be able to exercise influence over Vatican intervention into American affairs, as Cupich has done on issues in the past.

But McElroy, Cupich, and Tobin have not proven themselves especially influential among their brother bishops. So while they will have the ear of Rome, the most outspoken American cardinals may find themselves going in one direction, with the majority of the American episcopate going in another.

That will likely lead to more frequent clashes, even as the U.S. bishops have tried to schedule the more frequent opportunities for common prayer and Christian fraternity that Pope Francis has called for.

Some American Catholics have suggested there is another “message” in the appointment of Cardinal-elect McElroy: that the Holy See considers the McCarrick scandal to be concluded, and that additional questions about who might have enabled McCarrick will not likely garner much attention.

Next month will mark four years since revelations about former cardinal Theodore McCarrick emerged in the life of the Church — when McCarrick’s patterns of both child abuse and the sexual abuse and coercion of seminarians and young priests began to emerge in Catholic and secular media, and when Catholics began to ask questions about who knew what, and when.

McElroy was among those who had known something about McCarrick. Or at least, among those in the American episcopate who had been informed that something about McCarrick was not right.

After meetings with McElroy a few times, psychotherapist Richard Sipe, a former Benedictine monk and advocate for the victims of clerical sexual abuse, wrote to the bishop in July 2016, warning him about networks of protection and tolerance among sexually active clerics, especially those in positions of authority and influence.

The letter included warnings about McCarrick. The cardinal, Sipe wrote, “has been reported by numerous seminarians and priests of sexual advances and activity.”

“I have interviewed twelve seminarians and priests who attest to propositions, harassment, or sex with McCarrick, who has stated, ‘I do not like to sleep alone,’” Sipe wrote.

“One priest incardinated in McCarrick’s Archdiocese of Newark was taken to bed for sex and was told, ‘this is how priests do it in the U.S..’ None so far has found the ability to speak openly at the risk of reputation and retaliation.”

After he received that letter, McElroy declined to meet with Sipe again. Even when Sipe hired a process server to hand deliver a letter, McElroy turned down a meeting — saying later that Sipe’s apparently desperate behavior indicated he was untrustworthy.

Whether McElroy should have met again with Sipe is a matter of prudential judgment.

But the criticism that McElroy “covered up” for McCarrick may not reflect the facts.

The Bishop of San Diego is not the Roman Pontiff, and McElroy had no power or authority to investigate or discipline McCarrick when he received allegations against him in 2016. And he told America two years later that the information he received from Sipe was passed on to the relevant Vatican offices — although it was not directly stated that McElroy himself, or a staff member acting at his direction, passed on Sipe’s letter to Rome.

If McElroy simply filed Sipe’s letter, and the information was passed on some other way, then allegations that McElroy was negligent raise reasonable cause for concern about what his appointment to the College of Cardinals signifies.

But if McElroy did pass on Sipe’s letter to Rome, it’s not clear what more the bishop could have done.

Of course, it is not likely that either McElroy or the Holy See will provide more information on what happened with Sipe’s letter. But between now and the August consistory, the cardinal-elect may face pressure to more explicitly explain what he did with Sipe’s 2016 warning.

As a cardinal, of course, McElroy will be able to push for more transparency on the prospect that some clerics enabled McCarrick, and on the former cardinal’s unmonitored spending — if he chooses to do so.

In 2018, McElroy told America it is a “valid hypothesis” that the “personal sexual misconduct by bishops...was a factor which inclined some bishops not to vigorously pursue allegations of abuse among their clergy.”

Given those concessions, and his 2018 affirmation of much of Sipe’s work, McElroy could choose to press his brother cardinals in Newark and Washington, DC, to release the records which would indicate what prelates had financial entanglements with McCarrick.

The most lasting influence of McElroy’s appointment to the College of Cardinals will likely take years to be made clear.

It is obvious that the American cardinals will influence the appointment of the American episcopate, which means that the next generation of American diocesan bishops will be more closely aligned to McElroy-Cupich-Tobin than are the current members of the bishops’ conference — especially with almost two dozen diocesan bishops either already 75, or set to reach retirement age this year.

Whether McElroy himself is appointed to the metropolitan see of Boston, whose current archbishop is 77, or to another growing see, it is unlikely the cardinal is long-slated for ministry in San Diego. But wherever he goes, McElroy will have considerable influence over both the appointment of new bishops, and the selection of metropolitan archbishops across the U.S.

That will likely become the most influential aspect of McElroy’s membership in the College of Cardinals. While the cardinal-elect will get only one vote at the next papal conclave, and while he may now have limited influence at the U.S. bishops’s conference, McElroy will have ample opportunity to help to remake the map of the American episcopate in the years to come.

And the impact of that influence will be felt by American Catholics for decades.

Thanks for the good and balanced analysis, JD, although I have to admit I’m left pretty discouraged about all of this. It’s hard to feel hopeful about the future of the church when the future of the hierarchy is being stacked in only one direction. 😔

Even if Fr. Spadaro prophesied that a new cardinal would bring balance to the Force to the tune of three more bad Star Wars movies, I would be untroubled (Psalm 46). If the Pope wants to send me a clear message, he can write it down and have my parish's pastor announce it at Mass, as one does; otherwise I will just continue to live a life of prayer and penance like any sensible peasant in the Church in the United States, on the general assumption that this is very much needed for reasons beyond my own sins (which, to be fair, would already be reason enough).