Pillar subscribers can listen to JD read this Pillar Post here: The Pillar TL;DR

Hey everybody,

Today is the 16th Wednesday in Ordinary Time, and you’re reading The Tuesday Pillar Post.

If you’re not sure why you’re reading The Tuesday Pillar Post on Wednesday, well, I sent you a note about it yesterday. But the long and short of it is that Ed’s on vacation this week, I’ll be on vacation next week, and so we’re doing things a bit differently to adjust to being short-staffed. There will be a podcast this week, albeit without Ed, and I believe he’ll aim to make one next week as well.

Anyway, as you probably know, the 2024 Paris Olympics kick off in just two days, and will probably begin with some bit of avant garde made-for-television weirdness, some expression of the human spirit’s triumph via unusual dance and music, which is how the Olympic opening ceremonies tend to go these days.

My guess is that the toughest competition of the Olympics is between choreographers, who must certainly be in on the joke. I suspect they’re quietly competing to see who can stuff the most absurdity into his ceremony while still drawing breathless praise from NBC commentators, who want to be seen as smart enough to get the meaning behind the movement.

At least I hope that’s the case — I’d rather believe that the choreographers are having some fun with us than think this is the best we can do when it comes to contemporary dance and music.

So I hope it’s some kind of a game.

But in either case, I love the Olympics. I especially love getting into some obscure sport for two weeks or so, picking favorites and pretending to understand the strategies, and then forgetting all about it until the next Olympiad comes around.

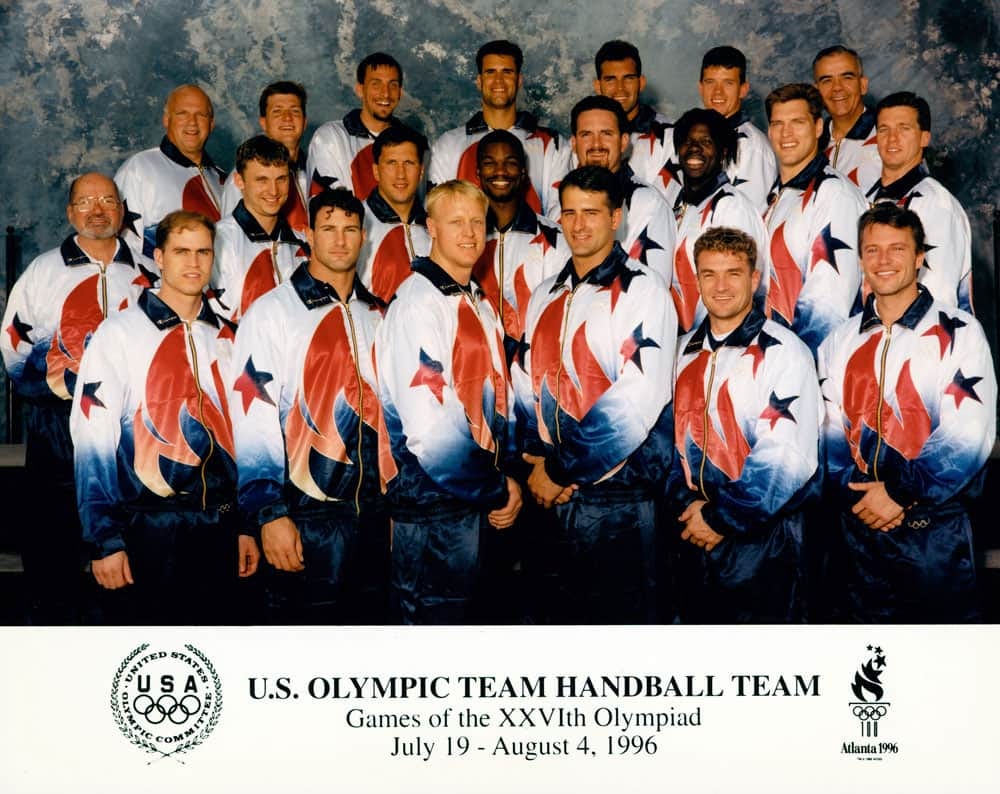

This year, I also loved learning that Bishop Emmanuel Gobilliard, along with a handful of priests, will spend the games living in the Olympic Village, offering Mass and hearing confessions for the 10,000 athletes living there. Among those priests will be Fr. Joe Fitzgerald of Rockville Centre, who was a member of the 1996 men’s Olympic handball team, at the Atlanta games.

We weren’t great at men’s team handball back then — going 1-4 in the group round, and beating only Kuwait. Still, making the Olympics is no small thing. And for the next two weeks, Fitzgerald, Bishop Gobilliard, and other priests from around the world will have a mission of mercy at the Olympic Games, inviting participants to prayer and to the sacraments — to Jesus Christ.

No word on whether priests get a role in the opening ceremonies.

The news

I spent most of last week, and the beginning of this week, in Indianapolis, at the 10th National Eucharistic Congress, the first such national event to be held in the U.S. since 1941.

The Congress is being hailed by a lot of people now as a life-changing event, and one which may be remembered as a significant point of inspiration in the life of the Church. So I tried to document each day what exactly was going on at the Congress — not only on the main Congress stage, but among the 50,000 Catholics who were in attendance, as well.

At the end of the Congress, and since it concluded, I’ve heard a lot of people compare it to 1993’s Denver World Youth Day, which was the catalyst for vocations, movements, and new apostolic projects across the United States. I’ve heard attendees say they believe the National Eucharistic Congress could be as significant a moment for the Church in the United States.

So in an analysis yesterday, I looked at some takeaways from the Congress. And I argued that the Congress does have the potential to be remembered as an important moment in the Church’s life — perhaps comparable to World Youth Day in 1993 — but that a lot depends on what happens next.

Here’s what I mean. And really, if I may, you should read this analysis. It’s a pretty good breakdown, if I say so myself.

But before I stop talking about the Congress, I want to acknowledge that some Catholics who attended — and whose judgment I respect — have been more circumspect about the Congress and its impact. In conversation with friends, I’ve heard some people saying that the Congress didn’t seem all that different from some of the other big Catholic conferences they attend, with major speakers giving talks to Catholics eager to line up after for selfies or book signings.

I’ve thought about that, and I want to qualify that my own experience of the Congress was shaped, as was everyone’s, by what I attended. I went to almost none of the big-speaker talks, especially during the day — because my reporting obligations meant that I attended as many liturgies as I could, and I otherwise spent as much as I could talking with people in attendance, doing interviews, and taking pictures.

Any event of 50,000 people is going to be experienced in a lot of different ways by the people who show up. But there are a few things that struck me about the Congress, as distinct from other big Catholic conferences and events.

First, while the Congress had a robust agenda of speakers, those were secondary on the schedule to the liturgies scheduled throughout the event. The Congress was — I realized a few days into it — primarily aimed at inviting attendees into worship, both at Mass and adoration. Much of the other programming was built around that, instead of being the main event.

Candidly, I think the Congress could have probably done with less speaker programming, and been no less impactful. And I’ve heard some pastors say that at future Congresses, it could probably do better at inviting ordinary parish priests and others involved in the Church’s daily life onto the stage, alongside some of the big name “Catholic celebrities” on the dais.

But in truth, the persistent positive feedback I hear about the event centered around Masses and, especially, nightly holy hours, far more so than on the rostrum of talks on offer. For the people who seemed to have conversion experiences at the Congress, the speakers were not often mentioned, at least as compared to the Masses and holy hours.

If there is an exception to that, it was the priests’ track of talks, which I have heard priests consistently praise as meaningful, because of the candor of the speakers involved, and a focus on healing and health in priestly ministry.

But for the most part, this was meant as an event centered around the Eucharist, not around big names, and I think the extent to which people experienced that probably shaped a great deal of their impressions.

Further, I think the extent to which that’s made abundantly clear for future Congresses — namely, that we are coming together to worship, and for worship, the more they’ll draw people.

The other reason I’m struck by the Congress as a significant event is because it was conducted in the name of the Church — it was, properly, an expression of the life of the Church, and not organized by para-ecclesial apostolates or movements. There’s something to that, because it expresses that the hierarchical constitution of the Church — her episcopate — wants Catholics to be gathered in that way to worship, wants Catholics to undergo a holy hour focused on healing, wants Catholics to experience liturgies as the center of their Christian life.

I find myself wondering whether that expression of the Church herself might be helpful in rebuilding and restoring trust the has been harmed in recent years between Catholics and their bishops.

Time will tell. For a couple of different angles on all this, read this analysis.

For more than 25 years, Logos has served as an interdisciplinary meeting point for scholars and readers to engage with the beauty, truth, and vitality of Christianity as it is rooted in and shaped by Catholicism. Published by the Center for Catholic Studies, University of St. Thomas (MN).

Cardinal Pietro Parolin made on Friday his first trip to Ukraine since before Russia’s full-scale invasion of the country in 2022. Why did he go?

—

Over the past few years, refugees have been fleeing Cuba at rates not seen, by most accounts, since the 1990s. Many of those refugees head to the United States. But a significant number of them also head to Spain, where more than 200,000 Cubans now live.

Fr. Bladimir Navarro, a Cuban priest who has lived in Spain for five years, is doing what he can to help those refugees. Navarro is the founder of a project meant to help Cuban refugees as they first arrive in Spain — often with no friends, no place to live, no work, and little money.

The priest says he wants to eventually return home to Cuba, but that his mission will last as long as Cuban people feel the need to flee their country.

You can read about Fr. Navarro’s work, right here.

What kind of changes? Read about them here.

—

Here’s a cool story.

It’s a big gift. But it comes with some rules. The diocese is supposed to spend the money over 10 years, and it is not supposed to use the money to create endowments, which might be invested to kick off annual revenue.

In other words, the diocese has to figure out how best to actually spend the money. Gary’s Bishop Robert McClory talked with The Pillar about that — and he said the gift is a big opportunity for the diocese to get out of its paycheck-to-paycheck school mentality, managing decline, and instead have a conversation about growth.

These days, that’s pretty unusual.

So how will they figure out how to spend the money? And what ideas are already rising to the top?

—

Snow sharks

While I hail from New Jersey, and spent a lot of my childhood summers in the ocean water down the shore, my wife and kids are all inlanders. She hails from Chicago, and they’re growing up here in Colorado, where the closest salt water is a Mormon-claimed saline puddle 520 miles to our west.

My wife has done a fair bit of traveling, of course, but for our children, the ocean is mostly just a concept they’ve gleaned from Moana and the story of Jonah, as foreign and mysterious to them as the choreography of French Olympic opening ceremonies.

In recent years, I’ve felt somewhat negligent in my duties as a father, for failing to provide my children regular access to the sea. Which is why I was delighted when a very kind invitation from a Pillar reader (in a good way) meant that our family can spend some time at a sandy beach next week.

While we’ll be staying along a large inlet with very few waves, Davey is somewhat convinced he’ll be a pro surfer within a day or two, and Max and Pia have been practicing songs from the Little Mermaid, in case they should happen upon Ariel frolicking in the surf.

But in recent weeks, a big topic of conversation in our home has been sharks. Sharks populate the inlet where we’ll be traveling. They are mostly small ones, not man-eaters, and while they don’t snatch children from the surf line every day, there seems to be a bite or two of a tourist’s leg just about every summer, requiring major stitches and leaving a gnarly scar.

Since I’ve positioned myself as the old salt of our family, and because I’m the dad, I have to pretend to be nonchalant about undersea hunters, but I’m secretly as nervous about a shark bite as anyone else. Last year, on a work trip to San Diego, I took a short dip in the crystal clear Pacific, which ended abruptly when a mostly-harmless leopard shark swam directly over my toes.

When I told the story later, I allowed for the listener to believe it might have been a tiger shark or a great white, and he might have flashed his rows of teeth before I bolted from the water.

On our trip next week, I’m especially anxious that a shark might nudge, graze, or nibble at my children, after I’ve promised Mrs. Flynn there is no such risk. I can think of few things more monstrous for a shark to do to me, personally, than to give my wife the impression that I’d lied to her.

Except eating one of the kids, I guess.

So while I’ve been telling the kids, and Mrs. Flynn, that we’ll be fine, at the same time I’ve been discreetly watching YouTubes about what to do if a shark should happen to follow after your children.

And the YouTubes had given me the false confidence of being prepared for shark-related emergencies.

Until I learned about something more terrifying than the prospect of great whites at the beach.

Yep. Cocaine sharks.

If you didn’t already know, researchers in Brazil published research last week which found that 13 sharks caught for a study off the coast of Rio de Janeiro all had cocaine traces in their livers and muscle fibers. A lot of cocaine, actually — more than 100 times the trace amount previously discovered in Brazilian marine life.

These sharks just can’t get enough snow, it seems — and so long as drug traffickers are happy to dump their wares when the DEA approaches, the sharks have got a steady supply. It’s possible the sharks are getting even more cocaine from — and this is gross — from sewage wastewater dumped into the ocean in the coastal cities where drug users frequently use the bathroom.

Again, that’s very gross. And very sad for the sharks, who probably don’t want to be on the cocaine.

If they stay on the coke, it will eventually wear them down. Picture sickly skinny sharks with chronic nosebleeds and sallow skin, smoking cheap cigarettes and talking wistfully about their glory days in a glam rock band.

I sincerely hope scientists can devise a way for these sharks to get clean — and also get pharmaceuticals, insecticides, and fertilizers out of marine bloodstreams, too.

But in the meantime, anyone dipping his toes in the ocean should half-expect a coked out shark to show up, probably wearing body glitter, to nip at people’s legs, and to talk with way too much enthusiasm about why David Bowie is under-appreciated by kids today. Or to drone on about crypto.

You can’t prepare for that. And really, just when we thought it was safe to go back in the water.

—

Please be assured of our prayers, and please pray for us. We need it.

And, if you subscribed lately, thanks for subscribing. We make news worth paying for, and we depend on you to do it.

Yours in Christ,

JD Flynn

Editor-in-chief

The Pillar