Happy Friday friends,

It is August 25, 2023, and today is the 100-year anniversary of a particular moment in the Catholic history of Western Pennsylvania, where I happen to be at the moment.

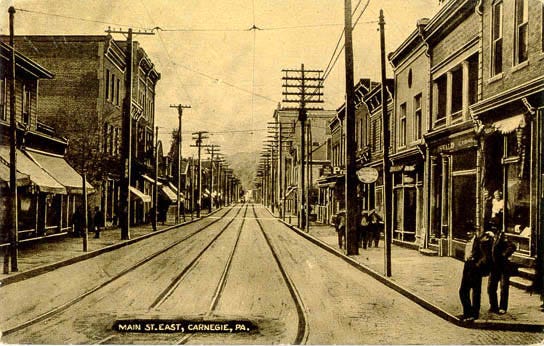

Today marks the centenary of the Carnegie Klan Riot, aptly named to describe what happened that time the KKK got it into their heads to march through the heavily Catholic town of Carnegie, just outside of Pittsburgh.

Their aim was to stick it to the papists, who were also overwhelmingly Irish immigrants and thus doubly objectionable. Things didn’t, as the word “riot” will have alerted you, go well for their little racist pajama party.

What happened was this: Having been banned by the mayor from marching through the town, some 25,000 (thousand) klansmen gathered on a nearby hill at dusk for the purposes of burning some crosses and initiating new members.

Once gathered, about half of the hooded hoard decided to march down into the town anyway, with the aim (at least according to local accounts) of burning a cross in front of St. Luke’s Catholic Church. Instead, when they crossed the bridge into town, the Klansmen were met with a hail of bricks and rocks, followed by a full blown street fight — with bats, hammers, and bullets being brought to bear.

The Klan was driven off, leaving one of their number dead behind them. Several dozen people were supposedly injured — two of them perhaps fatally. But that’s about all we know for sure, because no one in Carnegie was willing to talk to the authorities about the evening’s events.

The Pittsburgh Post Gazette reported that “Many men, dusty, torn, and apparently wary, some with unattended wounds and lacerations, and bruises, were seen in Pittsburgh restaurants and passing through the city in automobiles,” presumably the fleeing klansmen, fresh from getting their sheeted backsides kicked by the fighting Irish.

Back in Carnegie, the New York Times recorded that local citizens had failed to give the name of a single resident involved, and investigators couldn't locate even one eye-witness to the thousands-strong brawl.

Detectives couldn’t identify anyone injured in the fight, either. Hospital staff refused to name two men dying of serious wounds, believed to be local casualties of the fray, or disclose the circumstances of their admission.

A local undertaker, Patrick McDermott, was arrested for the death of the klansman, whose name I won’t bother to record, but the coroner’s inquest returned an open verdict and McDermott went free.

The silent solidarity continued, even after the klan’s local imperial wizard offered thousands of dollars in rewards for information leading to a conviction of the dead marcher’s killer.

So that’s some history for you. Here’s the news.

The News

New details have emerged in the case of Fr. Alex Crow, the Alabama priest who absconded to Europe with a teenager last month.

The Crow case has drawn a lot of interest, and raised a lot of questions about the 31-year-old’s time in ministry — how he came to be ordained, how he was able to groom and disappear with a teenager, and what the archdiocese knew, or was told, and when.

Crow’s relationship with the girl seems to have tracked exactly with his increasing focus n with the demonic, but as JD reports, sources who know Alex Crow say that they first started noticing problems with the priest about five or six months after his ordination.

—

Nicaragua’s government announced Wednesday that it has revoked the legal identity of the Society of Jesus in the country. The dissolution includes the seizure of all Jesuit assets and properties in the country and, potentially, the exile of the order’s members.

It’s the end of a long road for the Jesuits of Nicaragua and their relationship with the Ortega regime, of which they were once vocal supporters when the dictator first took power in 1979, amid the country’s "Sandinista Revolution."

So how did the Society of Jesus go from a position “support, but criticism,” which even the Jesuits themselves admit was often mostly just support, to becoming enemies of the state?

Edgar explains it all here, and this is a really worthwhile read.

—

The saga of the Arlington Carmelite monastery rumbled on this week, with the nuns releasing a statement walking back, sort of, their Friday declaration that they do not recognize the authority of their bishop.

In last week’s missive from the cloister, the nuns said they “no longer recognize the authority of, and can have no further relations with, the current Bishop of Fort Worth,” a statement which maps dangerously well onto the canonical definition of schism, as Bishop Michael Olson noted in response.

But, they continued, they “do not and will not recognize this bishop’s unwarranted and unauthorized abuse and wielding of the complete power he suddenly is trying to exercise over the Monastery.”

OK, I guess.

The thing is, Bishop Olson is — and has been since May —- the pontifical commissary (a title I’d never heard of before I read his decree of appointment from the Vatican) for the monastery and delegated by the Holy See to exercise “full governing authority” over the nuns’ community.

So, so far as I can parse their statements, they don’t reject Bishop Olson’s authority as diocesan bishop (in which he has defined and limited legal power over their community) but do reject his authority as pontifical commissary — which is granted to him explicitly by the Vatican.

I’m not sure that’s the fix their PR people — or civil lawyers — seem to have told them it is.

Don’t get me wrong, the nuns are within their rights to appeal the decree from the dicastery for religious institutes, and from what I understand they have. And they might otherwise have a strong case for doing so. But blasting out press statements about which ecclesiastical authorities they will and won’t recognize strikes me as unhelpful to their canonical cause.

That’s just one man’s opinion.

We’ll see what happens next. In the meantime, you can get up to speed on the story here.

—

Four priests have been ejected from a minor seminary in southern India for refusing to accept the uniform mode of celebrating the Syro-Malabar Church’s liturgy.

The “transfers” are the first consequences issued by Church authorities after the passage of a Sunday deadline for the clergy of the Archeparchy of Ernakulam-Angamaly to cease their years-long protest demanding that they be permitted to celebrate the Eucharist facing the assembly.

Archbishop Cyril Vasil’, SJ, the pope’s special envoy to the Syro-Malabar sui iuris Church, issued an ultimatum last week warning that the protestors had to decide if they were “with the pope, or against him,” and suffer the consequences of their actions.

It remains to be seen if the expulsion of the four priests will encourage other protestors to fall in line, or harden their resolve to resist their Church’s governing synod and, ultimately, the pope.

You can follow the latest developments here.

—

Vasil’ is now back in Rome for a pow-wow with Pope Francis before returning to India to continue his mission to bring the archeparchy’s priests and faithful into line.

They have a lot to discuss, and the tool box Vasil’ has to end a bitter and seemingly intractable dispute in the Syro-Malabar Church doesn’t offer many options.

But if making an example of four priests doesn’t have the desired effect, the archbishop is going to have to change tack. He can’t transfer or suspend all the rebel priests of the archeparchy without effectively shutting down the sacramental life of half a million Catholics.

As I noted on Tuesday, if he really wants to avoid a full blown schism — either within the Syro-Malabar Church or between it and Rome — it seems to me a reset is needed to allow everyone a chance to start fresh. Key to that could be the major archbishop and head of the Syro-Malabar Church, currently Cardinal George Alencherry, who has been effectively missing in action for the whole of the escalating dispute.

Alencherry had to step back from his day-to-day role as head of the archeparchy because of a civil law case over a controversial land deal. There’s no clear timeline for his return to leadership, and he is 78 years old.

Could the cardinal’s retirement pave the way for a fresh face and new voice to help end the Syro-Malabar crisis? It’s a longshot, but I think it might be the best bet at this point.

You can read my whole analysis here.

—

This month, two more U.S. dioceses issued policies requiring priests to seek permission to celebrate the ordinary form of the Mass facing ad orientem.

There are a number of ways you can look at this trend.

One way, and I think this is interesting, is to see these policies as part of the broader implementation of the norms of Traditionis custodes in U.S. dioceses - indeed the content and context of many bishops’ policies make this link explicit.

But Traditionis doesn’t actually say anything about ad orientem celebration of the ordinary form of the Mass, let alone require bishops to do something about it.

It seems to me that what we’re seeing here is a kind of liturgical mission-creep coming into the Church in the U.S. But what makes it especially puzzling is that the bishops’ stated reasons differ markedly from place to place, and are by no means wholly negative.

Often, bishops seem concerned only to ensure that big liturgical changes aren’t made by priests without properly preparing their parishes to receive them well.

Bishop Zubik in Pittsburgh, for example, wrote that he wants to be “perfectly clear” that “this policy is not meant to be seen as a forbiddance of celebrating Mass ad orientem. Rather, I’m trying to say ‘Yes, you can do this, here’s how.’”

In other places, like Chicago, the bishop (or in that case cardinal) seems pretty clear that ad orientem worship, in English, according to the ordinary form of the liturgy, is suggestive of a rejection of the legitimacy of the Second Vatican Council II.

I think those different concerns are fascinating.

But there’s something else I think is even more pressing here, as news:

Whatever the bishops’ motives, the question I think merits asking is: Are any of these policies legal, canonically speaking?

The standing guidance from Rome seems to say they’re not, nor is there a clear legal rationale for arguing they could be — apart from a kind of general theory of total executive power.

That could change, of course, if any of them were appealed to the Dicastery for Divine Worship — the leadership there has been known to take an expansive view of its own authority. But in the meantime, we seem to have bishops passing policies that restrict previously recognized rights of priests without any obvious or coherent canonical rationale for their power to do so.

That’s a big deal. It’s not to say these bishops are badly motivated, or they are inventing problems to justify their actions. But it is part of a much broader question of the rule of law in the Church right now — namely: do we have it?

If we don’t, that’s kind of a big deal. As Pope Benedict XVI once observed, a society without laws quickly becomes a society without rights, and this is as true of the Church as any of other society.

So, for that reason, I think this story is one to watch.

No Touchee Run

As I mentioned, this week’s newsletter is coming to you from Western Pennsylvania.

I’m telling myself, promising myself, perhaps kidding myself, that I will snatch a few days vacation with my family before returning to DC next week, when our daughter begins Montessori preschool.

While sincere enough in my intention to take at least a few days off, I never seem to actually manage it. But even if I do end up working the whole time, the change of scenery makes a lot of difference to me.

I think I have written before about this slightly dilapidated lake house which my extended family share between us. It was built about 60 years ago by my grandparents as a summer getaway for their eight children.

Today it hosts a revolving circus of their 100-plus grandchildren and great-grandchildren, who cycle through in groups of 20-30 people at a time. Those figures belie the number of bedrooms, which you can count on one hand, and the number of bathrooms, for which you’d only need two fingers.

It requires a lot of love and a deep sense of family to be here, and that’s a good thing.

I usually reread my favorite book when I come up, Norman Maclean’s “A River Runs Through It.” Although set in a different time and place, one passage has always struck me as being equally appropriate to my particular here and now:

“Painted on the side of our Sunday school wall were the words God Is Love. We always assumed these three words were spoken directly to our family and had no reference to the world outside, which, I soon discovered, was full of bastards, the number increasing rapidly the farther one gets from Missoula, Montana.”

He might as well have said Crawford County, Pa., as far as I’m concerned.

This place is the only fixed spot on the map for me. Having moved around a lot as a kid and an adult, there is no childhood home to visit, nor really even a hometown to return to for me. This lake is ground zero for my life, my memories, my family, and — I hope — the best of what I have still to look forward to.

It’s not around the corner from Washington, but I’ve learned to love the drive up as a kind of hours-long exercise in anticipation, mentally ticking off the familiar and unusual place names along the way as my daughter screams sweetly over my shoulder.

One of my favorite mental markers is the defensively named No Touchee Run, which appears on the map as I wind through the Alleghenies.

I have absolutely no idea what gave that particular creek its name, but I like to imagine there is a good story there. Possibly involving an early backwoodsman or moonshiner protective of his water source. It could be.

In his memoirs as a young man serving in the United States Forest Service in 1919, Maclean describes wonderfully his colleagues' efforts to preserve another uniquely named local waterway from a Puritanical surveying crew:

“They had been over on the north fork of the Clearwater and of course had run into Wet Ass Creek,” so called, apparently, because of what happened if you tried to make your way down the steep banks on either side.

“More troubled about the name of a creek than where it went,” as Maclean describes them, “they were divided as to whether they should put down its real name on the map they were going to submit to the drafting room.”

One faction, supported by Maclean and the local rangers, was for recording the creek’s right title.

“Too much of the West had been named after some guy’s home town in Minnesota or Massachusetts or even after the guy himself or after a bear or a deer. ‘There are only five thousand Deer Creeks in this country. Let’s keep America’s only Wet Ass Creek,’ we argued.”

“The other bunch, who would also soon be spending a summer of money on a night with the whores of Hamilton, argued that many who worked in the Forest Service’s drafting room in Missoula were women and would be offended by having to copy such language with their own pure hands.”

The matter was put to a vote and those in favor of Wet Ass being rightly called won the day. Or so they thought: “In the end, though, it turned out the joke was on us.”

“On the next map of the Forest, it appeared all as one word and a final e had been added, which henceforth was pronounced and the a was made in Boston. Now it doesn’t mean anything but be sure you pronounce it Wee-tah-see Creek just as if its headwaters were on Beacon Hill.”

I don’t know the story of No Touchee Creek, but I hope it’s half that good. And I really hope it involves a grizzled old moonshiner, preferably someone who looks like Popcorn Sutton.

See you next week,

Ed. Condon

Editor

The Pillar