The Belgian paradox, a heart of darkness, and Apocalypse now-ish

The Friday Pillar Post

Happy Friday friends,

And a very happy feast of St. Pius of Pietrelcina — you know him as Padre Pio.

I am going to be totally upfront with you: this newsletter is not going to be a ray of sunshine in your inbox. And for that reason, I am especially grateful for the feast of Padre Pio today. He was a saint, as John Paul II said at his Mass of canonization, whose “holiness cannot be understood without constant reference to the Cross.”

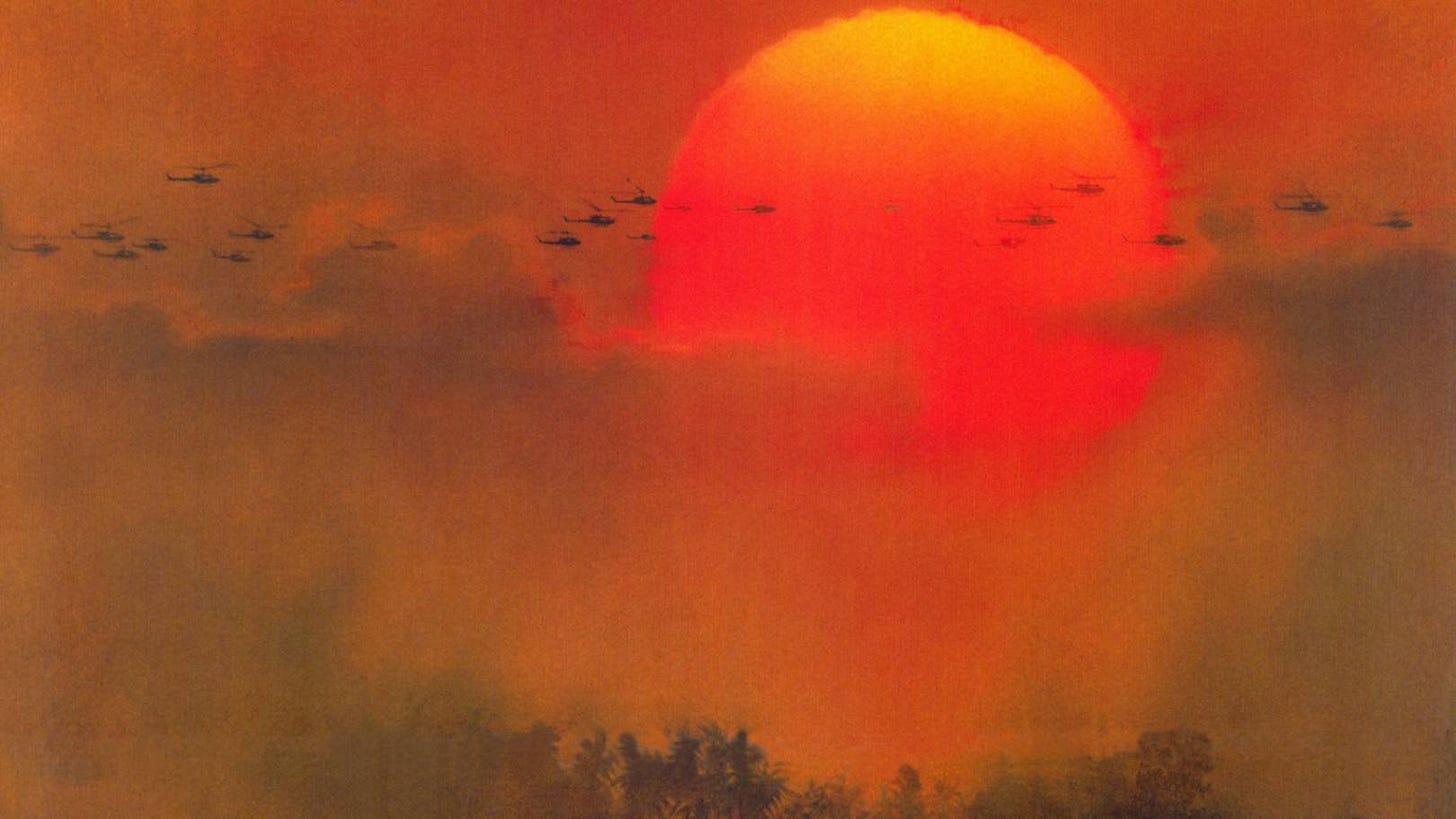

Today, I need Padre Pio’s witness to suffering for the Church, and his tirelessness in spiritual combat, because — on just about every front of global and ecclesiastical affairs — things seem to be headed upriver at speed.

And while I don’t presume to know how things are going to shake out, it’s my best guess that it’s all likely to get worse before it gets better.

This being the case, I’d love to bring you some distracting trivia about Padre Pio, maybe some celebrity clickbait about Shia LeBeouf, the somewhat scandal-prone actor who played the saint in a recent film and says he’s now converted to Catholicism.

But I can’t do that.

For a start, I think celebrity converts should be, in the most pastoral way possible, ignored for at least a year or two by Catholics in the public square.

Anyone coming into the faith will — by that very fact — be in the throes of powerful emotions. It is an unsettled time; that’s what follows any life-changing event. Having the doors of grace opened to you is the most life-changing of them all.

The Church, by the way, recognizes this reality.

Neophytes, the newly baptized, are given basically a honeymoon to settle into the faith, and are not supposed to assume certain roles and responsibilities until a little time has passed — like being ordained or entering religious life. It seems both unfair and unhelpful to make too much of celebrity converts, if for no other reason than they are just beginning to unpack the wonders of the faith, and can hardly be expected to be effective apologists for it.

And even if I wanted to write about some celebrity actor, we don’t take time off from the real news at The Pillar. Even if we want a break now and then, as some guy once said: It was written I should be loyal to the nightmare of my choice.

So with that in mind, here’s what we have been covering:

The News

We have been tracking this week the publication by Belgium’s Flemish bishops of a new document on the pastoral care of Catholics who identify as LGBT, which includes the outline of a ritual of blessing for same-sex couples.

This is likely to be a topic of conversation when the Belgians head upriver to Rome for their upcoming ad limina visit, during which they will meet with the pope and heads of the various curial departments. That was supposed to happen next week, but the visit was postponed until November.

You can read all about it here.

Belgium is, by the way, a fascinating country with quite an interesting history. It has also played, and continues to play, an outsized role in the life of the global Church — its thinkers and leaders have played a big part in shaping the decades post-Vatican II.

You might ask how the Belgian bishops could possibly get away with adopting an idea that the Vatican’s doctrinal office so recently terminated, with extreme prejudice. Surely this is a recipe for a serious breach of communion with Rome?

For the last several years now, Rome has been issuing “no” after “no” to various “progressive” plans coming out of different European bishops’ conferences, most often the German one.

But with the pope usually disinclined to settle matters directly, things have settled into a kind of a punt — a frosty “Whatever. We’ll talk about it at the synod next year.”

But it seems that some bishops are no longer prepared to wait that long. Why?

The answer, most Vatican sources suggested, is the pope.

In the standoff between the Vatican’s doctrinal department and the Belgians, both sides have invoked Francis’ own teaching to support their positions, even quoting from the same documents. And the two sides of that argument represent a broader split between rival camps, which both support the pope’s reforming agenda and see themselves as natural heirs to it, but interpret it very differently.

On the one hand, there are what we can call the “pastoral institutionalists,” who see Francis’ great work as setting the Church’s unchanging teachings to new, more welcoming music. On the other are the arch-progressive reformers who, like the Belgian and German bishops, want to see real, substantive change on issues like the ordination of women and same-sex relationships.

The arch-prog camp does seem to be getting bolder. Some suggested their strength is just an accident arising from the weakness of others. But a more compelling theory, to me at least, is that they are growing impatient and increasingly doubt that Francis will deliver for them after the 2023 synod, if his pontificate lasts that long.

Instead, it was suggested to me, they are looking to provoke a confrontation now — setting the stage for a conclave that will (so the theory goes) have to elect a pope prepared to stop a schism at the expense of universal teaching authority. And candidates for this role are already being quietly floated around Rome.

I’m not sure this is the explanation for what’s going on in the Church right now, but I’m absolutely convinced that the pastoral-institutional/arch-progressive split is going to be the most important dynamic in the next conclave. Absolutely more so than the hackneyed conservatives vs. liberals stuff we are bound to see.

In the meantime, the Belgian proposal seems sure to be adopted by bishops’ conferences in some places, and condemned by others. As these dominoes start to fall, the divisions in the Church will only become more intractable and — it seems to me — the possibility of schism that much more likely.

You can read the whole analysis here.

The deputy chairman of the German bishops’ conference knowingly left accused abusers in office in his diocese, and even appointed them to roles where they could abuse again, an independent report found this week.

The review of historical cases of clerical abuse in the German Diocese of Osnabrück, released on Tuesday, found that Bishop Franz-Josef Bode “repeatedly left accused persons in their offices, even those whose danger could hardly be doubted, or appointed them to offices that made further opportunities for committing crimes possible… [he] even entrusted them with leadership tasks in youth pastoral care.”

Bode has led the diocese since 1995, and been the deputy leader of the bishops’ conference since 2017. He is also one of the four members of the German synodal way’s executive committee.

On the day of the report’s release, the bishop took responsibility for its findings, and expressed his remorse. But he also gave himself credit for making the report happen in the first place:

“I had wanted this interim report so that the truth would also come to light as quickly as possible. Now I am very concerned about how blind we have actually been and how blind I have been for the suffering and the perspectives of those affected.”

It also noted, however, that “this [promise] was not implemented in his diocese’s administrative practice toward those affected.”

Osnabrück is the latest in a series of German dioceses to publish independent reports into historical clerical abuse cases. Following reports in their own dioceses, Cardinal Reinhard Marx and Cardinal Rainer Woelki both offered their resignations to Pope Francis.

On Thursday, Bode announced he would not be making a similar offer to the pope. Instead, he said, he had spoken with Fr. Hans Zollner, SJ, of the Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors, and decided to remain in post.

While the bishop acknowledged that he “acted negligently in some cases,” and that his “credibility is severely damaged,” after “intense consideration” he decided to carry on in office to oversee the implementation of the report’s recommendations.

“I want to be measured by this commitment,” he said in his press conference.

You can read more about his statement, and his decision to remain in post, here.

It’s hard to understand how, in 2022, more than three years after Vos estis lux mundi, a bishop can accept that he moved predatory priests from one assignment to another for years, “decades” even, and still feel his resignation shouldn’t be at least offered.

That Bishop Bode’s decision to carry on in office apparently came out of a conversation with the Vatican’s front man on ecclesiastical accountability in the face of the abuse crisis, Fr. Zollner, is even harder to understand. And it raises some real questions, which JD asked in an analysis this morning.

Did Zollner recommend Bode not resign? If so, it seems reasonable to ask what kind of negligence in office the founding president of Rome’s Child Protection Center does think demands a resignation.

On the other hand, perhaps Zollner told Bode to go — or at least offer the pope the option of his resignation, as other German bishops have done after far less personally damning reports. But if he did, it would be remarkable for Bode to lean on the priest’s credibility while flouting his recommendation.

As his prayer intention this month, Pope Francis has asked Catholics to pray “that the death penalty, which attacks the dignity of the human person, may be legally abolished in every country.”

The United States is, of course, in the roughly 25% of countries that still execute people. And while successive popes have spoken against the practice and in favor of the absolute sanctity of human life, in this country capital punishment raises all kinds of questions of injustice in practice, not just in theory.

They talked about what the Church teaches, what the popes have said, and how the United States compares to other nations in its use of the death penalty — and how the practice of it is connected to real racial injustice and structural inequalities.

The numbers don’t lie on this one. It's hard to escape the conclusion that, whatever the theoretical rights of the state to take life, our use of the death penalty is not justice at all, but a heart of darkness at the center of our legal system.

I strongly urge you to read the whole conversation here.

Airport authorities in Bogotá recently made the decision to close a Catholic chapel in the terminal of El Dorado International, one of South America’s busiest hubs.

While that might not sound like headline news, the plan has become the epicenter of a national debate in Colombia about the role of the Church in public life.

The move has sparked popular protests at the airport itself, and the public debate has drawn in the bishops of two dioceses, El Dorado’s management company, and Bogotá’s mayor. It now looks like the airport chapel is set to reopen – in fact, a local bishop announced last night an agreement has been reached. But another fight over another chapel, this time in the country’s Congressional building, is still underway.

Just a reminder, please, that the reason we’re able to bring you news of what’s happening in the Church in places like Latin America, Africa, and of course Ukraine, is because of our fantastic correspondents on the ground there.

Keeping this journalism going depends on the support of our readers: you. So if you are a paying subscriber, thank you.

And if you’re not, sincerely, please give it some thought. We ask for $5 a month, or more if you have it. And you’re not just helping to pay our writers, just as importantly you’re helping us keep their work free to read as a service to the Church.

The Horror

I am sure you, like me, have been following the developments in Russia this week.

President Vladimir Putin has, under the fiction of “popular referenda” in the regions of eastern Ukraine, put the world on notice that he intends to declare the areas to be sovereign Russian territory.

The purpose of that, learned opinion seems to hold, is to claim any attempt to liberate those areas from Russian control is a Western-supported invasion of Russia proper — and justify any use of force to repel it. To that end, Putin has already announced the mobilization of 300,000 reservists, and begun rattling the nuclear saber.

There are a couple of ways to look at this development, which I’ll come to in a moment. But before that, we should stop and consider what these regions under Russian control are being subjected to: torture, murder, rape, and mass deportation.

The Russian track record of war crimes is now desperately long, and Pope Francis went further than ever in his public statements about the war on Wednesday, referring to the list of atrocities in “martyred Ukraine.”

Pope Francis #Ukraine: "Cardinal Krajewski told me about the savage actions, the monstrosities, the tortured corpses they find. Let us join these people who are so noble and martyred."#PopeFrancis #GeneralAudience pic.twitter.com/YPpbAxbvs8

— Vatican News (@VaticanNews) September 21, 2022

As winter approaches, and Russia uses its stranglehold on Europe’s energy pipelines as a weapon, people in Ukraine — families, children — are going to freeze. Things are going to get a lot harder across Europe, too, and likely further abroad. And there is going to be some talk of finding a way to make peace with Putin’s Russia.

I’ve got no informed opinion, or personal standing, to weigh in on those calls now, or later. But when they come, we need to remember that every time someone talks about ceding “territory” to Putin, that means surrendering the people there too.

It means leaving them — families, children — to what Pope Francis is now calling martyrdom.

That being said, it seems to me that Putin’s effort to freeze Ukraine into submission, and to intimidate the West into washing its hands of the situation, might be the least terrible and terrifying possibility for the next few months.

Experts have poured cold water on the idea that Russia is actually capable of fielding and equipping anything like 300,000 reservists anytime soon. The balance of probability seems to be that Putin’s threat of nuclear weapons is still (just about) more likely to be a bluff than earnest willingness to court an Apocalypse.

But that rather prompts the question: Why is he doing it? Certainly not to cement popular opinion. Putin’s mobilization announcement seems to have divided fighting-age Russians between those taking to the streets in protest (leading to thousands of arrests) and those just flat-out fleeing the country.

So, if the threatened escalation is unpopular at home, and being treated as madness abroad, who is this for?

The unpleasant conclusion that suggests itself is that Putin is under serious pressure from ultra-nationalists within his own security services and military. And this isn’t just my application of the principle of parsimony.

While it might surprise anyone to learn Putin has a wing to his right, he does, and it has put him under serious pressure following Ukraine’s unexpected advances earlier this month, which retook thousands of square miles of Russian-held territory.

By coincidence, as the Ukrainian army was rolling up the northeastern front on the evening of Sept. 11, Moscow was kicking off its “Day of the City” carnival, where Putin opened the Sun of Moscow, Europe’s largest ferris wheel.

The wheel was immediately hacked, and its passengers left stranded for hours. And it was Russian nationalists who took credit for it, posting a denunciation of the establishment as a “rotten liberal intelligentsia” enjoying fireworks while “our boys are dying on the front.”

While these might appear like minor data points, I have yet to find a Russian expert who thinks any of this would have been possible without a green light from the FSB, the Russian intelligence service.

We’ve written a lot about Putin’s vision of Russkiy mir, a “Russian world” underpinned by revanchist imperialism and religious nationalism. But the thing is, while Putin might be fighting under its slogans, he didn’t invent them — he adopted them, along with the ultra-nationalist political fringes who did come up with them.

Analysts might go back and forth on how much of this stuff Putin buys into as a creed, rather than a political mantle to throw over his sheer will to power. And who knows, the mind of man is capable of anything. But it does seem clear that, for some very serious people in the security services and military, Russian victory is an article of faith — to be achieved at any cost.

All this is to say, the nightmare may not actually be Putin deciding to go all-in to keep the territory that Russia currently occupies in Ukraine, though he may. Given the Russian lives he’s already spent on his “special operation,” how many Ukrainian lives do you think Putin would sacrifice to shore up his own position?

If Putin's survival in power demanded it, would you bet against him bombing a Ukrainian nuclear power station, or deploying a strategic nuclear weapon to show he isn’t kidding around? I wouldn’t.

But the real apocalyptic scenario is that keeping the territory Russia still has in Ukraine, at whatever cost, won’t be enough to satisfy the people behind Putin who would, in total sincerity, prefer nuclear war to a perceived Russian defeat.

It’s a sobering thought, I know. But, well, I told you this newsletter wasn’t going to be a ray of sunshine.

So what is the Christian answer to all of this? Well, Padre Pio’s famous maxim "Pray, hope, and don’t worry" comes to mind.

Prayer is, as that saint could tell you, not a cop-out or an escape from reality. On the contrary, it is labor, combat even. It is a battle of faith against despair. It is a sincere engagement with the world as it really is — under threat but also before God.

“Don’t worry” doesn’t mean don’t care. It means believing, and salting the Earth with the belief, that Christ has conquered death. A Christian sees the world, dark as it may appear, in the light of the Cross — the symbol not of death but of the triumph of life over it.

So don’t worry, but pray like crazy.

See you next week,

Ed. Condon

Editor

The Pillar