Summary justice? What is an ‘extrajudicial process?’

Fewer procedural norms, but a higher bar of proof

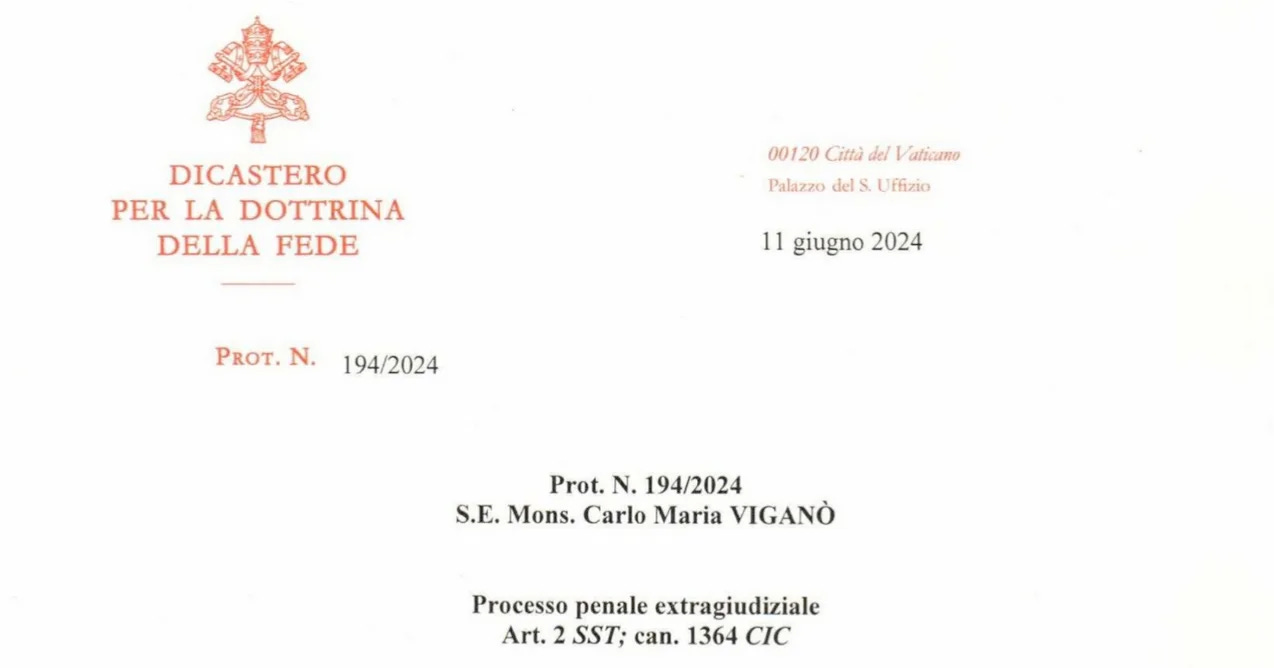

The news broke this week that former apostolic nuncio Archbishop Carlo Maria Vigano is facing formal charges of schism — the refusal of submission to the Roman Pontiff or of communion with the members of the Church subject to him.