Happy Friday friends,

And a very happy St. Patrick’s Day to those who celebrate — they being Americans, mostly.

I’m going to be honest with you, I’ve come full circle on Paddy’s Day.

As a kid in Chicago, I thought the whole dying-the-river-green-thing was cool, and my parish and school dripped with the kind of lucky charms schlock you’d expect. I loved it. I actually rode on a float in the Chicago parade once.

When I got older, and moved to the U.K., I came to see St. Patrick’s Day — like Halloween and Valentine’s Day, though with fewer ghosts and candy hearts, and more green beer — as embarrassing pieces of American cultural kitsch with nothing at all to do with their pious namesake days.

To me, the whole thing smacked of, at best, what I tend to think of as “cultural Catholicism,” the fringe trappings of faith unmoored from the ballast of any underlying belief.

I’ll admit, I pulled away from St. Patrick’s Day even more as (again like Halloween) American-style decorations began popping up across the U.K. I felt more than a little national guilt-by-association about exporting our Disneyland take on saints’ days.

But I’ve come around again in the last two years. I’ve come to see a lot of St. Patrick’s Day fanfare being, rather than a bootleg take on supposedly “Irish” culture, unashamedly American and self-consciously rooted in the Catholic immigrant experience.

That I can dig.

I’m not saying I’ve suddenly changed my mind on verdant lager, and let’s be honest, boiling a brisket in the land that invented BBQ is, or ought to be, a sin. But I’m going to take advantage of my local bishop’s generous dispensation to celebrate the day, Friday in Lent notwithstanding.

And while we’re on the subject, if you missed our explainer on who is dispensed, and who can dispense you from the Lenten fast today, you can read it here.

That explainer also includes the full text of maybe the most tubthumping, rah-rah American episcopal decree I’ve ever read. So don’t miss that.

And for those of you who aren’t dispensed, we have a little Lenten Friday treat for you.

As some of you may know, before he became our data supremo and whatever-it-is-exactly-he-does-for-a-day-job, our own Brendan Hodge was a menu pricing manager for Wendy’s — he would size up the competition’s offerings, and make sure Wendy’s was the best bang for buck on the market.

So we asked Brendan to turn his professional eye on the great American Lent tradition: the fast food fish sandwich. Yeah, you’ve probably read a dozen “Which fish sandwich is the best?” pieces over the years, but that’s all just opinion.

Here at The Pillar, we don’t post commentary, we bring you serious, informed, expert analysis. That’s how we roll. Why should fast food, or QSR as they call it, be any different?

Brendan breaks down the economics of the sandwiches, the cost-benefit breakdown of going for a value-versus-premium offering, who’s giving you the most protein, and who’s winning the price war. He’s got charts and graphs and everything. Heck yes.

Brendan will also tell you which one he thinks tastes best, too, if you’re interested. But that’s kind of an ugly baby competition, really, isn’t it?

No one likes a fish sandwich. Eating one, let’s be honest, is an act of penance slightly above just skipping the meal entirely — it’s worse than nothing. But American Catholics eat them, a lot of them, in Lent. I’d imagine for the same reason Scottish people put salt on their porridge year round: just to be a little extra miserable.

Still, none of this means the economics aren’t fascinating. Read the whole thing.

The News

Archbishop Alexander Sample of Portland was elected to the U.S. bishops’ conference executive committee this week.

Sample was elected Tuesday by the conference’s administrative committee (a different thing) to become the executive committee’s at-large member, making him the only bishop in the executive group who doesn’t serve ex officio from another role.

Sample is generally considered a theological conservative, to the extent that words like “conservative” or “liberal” have any real applicability or value when talking about ecclesiastical affairs — we’ve found over the years that labeling the various groups among bishops is an inexact and tricky science.

But call them what you will, Sample now joins a committee with some decidedly like minds at the conference’s top table, where he will serve alongside conference president Archbishop Timothy Broglio, VP Archbishop William Lori, secretary Archbishop Paul Coakley, and treasurer Bishop James Checcio.

His election by the administrative committee, made up of committee chairmen and regional representatives of the conference, is telling.

Despite the decision to hold more of the bishops’ conference sessions behind closed doors, divisions among the bishops have increasingly spilled over into public view. Some, like Cardinal Blase Cupich and Cardinal Robert McElroy, have taken to writing controversial essays advancing tendentious views about issues like the synodal process and the revision of Church teaching.

That has provoked others, including Bishop Thomas Paprocki and Archbishop Samuel Aquila, to respond, challenging their views and, at least in one instance, raising the issue of potential material heresy.

But however divided the bishops may be, across a growing number of issues, Sample’s election (following on from November’s presidential and committee polls in Baltimore) would seem to confirm the bishops are not evenly split — there is a clear majority and minority view of things.

How long that majority consensus lasts is open to question, though. With a large percentage of U.S. bishops due to reach or pass the retirement age in the coming five years, to say nothing of those already serving past the age of 75, the conference is set for a generational turnover in the nearish future.

You can read all about Sample’s election, and the USCCB’s recent voting trends here.

—

Following last week’s concluding session of the German synodal way, the deputy chairman of the German bishops’ conference invited Catholics in his diocese to contact parishes for liturgical blessings of their same-sex partnerships.

Bishop Franz-Josef Bode’s call for people to come forward was followed swiftly by the conference president, Bishop Georg Bätzing, giving an interview in which he said such blessing were already happening in German parishes, that they were a good thing, and the German bishops are committed to getting it all out in the open.

The bishops’ insistence that same-sex couples can and will receive blessings the Vatican (with the personal endorsement of Pope Francis) quite recently declared impossible for the Church to give struck many as an explicit rejection of Roman authority.

Surely, many have said, Bode and Bätzing have finally jumped the synodal shark — this must be schism, right?

I’m not saying I buy it, and I might fancy my chances fighting the case in court, but either way, the Germans’ latest stand is egregious, clearly in defiance of the pope, and absolutely a rejection of some fairly clear theological truths outlined by the Vatican’s doctrinal department. And Bode’s invitation for couples to call their parish to schedule a service seems like an open and shut example of the canonical crime of incitement.

For myself, I think the most likely outcome in the near term is this: Rome and Pope Francis are unlikely to take any definitive action this side of the meeting of the synod of bishops in October — and probably not before the close of the synodal process the following year either. The preference will probably be to hash the whole thing out in the synodal hall, with the whole world weighing in, and thus to avoid a direct face-off between the Vatican and Germany.

As a kind of de-escalation tactic, I get it. And it’s true that the German situation is primed to hit formal schism at a moment’s notice, so wanting to take a deep breath is understandable. But I also think this will strengthen the Germans’ hand.

Their aim will be to arrive for the synod in Rome already doing all the things the Vatican has told them are theologically impossible. When the debate begins, the Germans’ won’t be arguing theology, tradition, natural law, or scripture — they don’t want to, and on those grounds they will lose.

They want to arrive ready to argue their facts on the ground (“lived reality” I think is the preferred synodal terminology) versus an abstract discussion of Church teaching. In short, the German bid is to paint the Vatican as wedded to theory and divorced from reality.

At this point, I think it will take either enormously subtle maneuvering or an historic act of papal will to bring the Germans back in line, if that is still possible. It’s anyone’s guess which, if either, Francis is planning to deploy. We will see, I guess.

On the subject of the German plans for blessing same-sex couples, you might be forgiven for thinking that it’s all of a piece with a recent proposal from the Belgian bishops for something similar.

Indeed, before the German synodal way voted last week, Belgium’s Bishop John Bonny described to them how he and his colleagues came to publish a text allowing for a ritual blessing of same-sex couples last year.

But as Luke Coppen explained in an analysis this week, there are actually some possibly crucial differences in how the Belgian and German bishops are approaching things, and this could shake out to very different responses from Rome.

—

This week, we also reported on a new study of fraud, theft, and other financial crimes in the U.S. Catholic Church.

It’s a fascinating article.

A lot of the “opportunity” comes from exactly where you’d expect: parish life involves a lot of cash, a lot of personal trust, and invests the pastor with near total financial authority. But the pressures and rationalizations which can lead a priest to fleece his flock are very interesting — as are some of the examples cited.

I won’t try to summarize the whole thing for you here, but I would encourage you to read our report. But there were a couple of key takeaways:

The number of individuals found to be involved in priestly financial fraud, as a fraction of the U.S. presbyterate, is tiny.

Despite parish life and the priesthood seeming to provide a “target rich environment” for stealing, the priesthood seems to attract almost no one predisposed to take advantage of it; the priests who do break bad financially tend to do so in their 50s and after decades in ministry.

The factors that drive financial crime tend to be, at their core, disaffection with ministry and the all too human pain of feeling unappreciated, isolated, and afraid of their sins.

Can the Church do better with financial safeguards, regular auditing, and transparency? Absolutely. But it seems to me, if you really want to help take a bite out of parish crime, you can do it best by taking care of your pastor.

Healthy priests — mentally, physically, morally, spiritually — don’t tend to break bad. Unhealthy ones tend to break down.

Taking good care of our clergy is on all of us. It’s St. Patrick’s Day, go buy Father a beer.

—

I want to stop here and just say something really quickly. There’s a lot of grim stuff in here this week, I know. It’s what it is: we don’t make the news, we just report it. But, and I mean this, you need to not let it get to you - because it can. Hard stories about abuse, sin, crime, schism, make for hard reading and it can take a toll. Believe me, we know. It gets to us too.

Sometimes JD and I have to call each other and basically self-report for “sunshine duty” for a week or two and, if we can’t only work on good news stories, at least take a break from the really hard to deal with stuff.

So if all this is getting to you, stop reading. I mean it. Take a break. We’ll still be here doing the work, but you don’t have to follow every turn of the wheel along with us.

God is love. The faith is true. The Church is alive and, on the whole, her priests are faithful, loving ministers of grace. Don’t let the news make you lose sight of any of that, because it’s all infinitely more important.

—

A deacon from the Diocese of Brooklyn was sentenced to 16 years in prison this week, after he admitted to prosecutors that he engaged in sexual acts with minors he met on the hookup app Grindr.

The judge in Vega’s case highlighted the need for “deterrence” in preventing similar crimes. And Vega is one of a growing list of Catholic clerics to use hook-up apps like Grindr to make sexual contact with minors — some deliberately and some unwittingly. And there are several academic studies demonstrating the risks these anonymous sex platforms pose to kids.

Yet, for some reason, pointing these risks out or suggesting the Church ought to be confronting them head-on is treated as a kind of hysterical homophobia by many secular and even Catholic media and commentators.

To me, observing that platforms used to facilitate anonymous sexual contact and encounters are downright dangerous seems blindingly obvious. The chief argument against ecclesiastical authorities treating them as such appears to be that not every cleric who uses such a platform either wants to or will encounter a minor, either intentionally or accidentally.

And let’s stipulate: that’s the case. So what? The Church shouldn’t act to mitigate the known risks because it would be… unfair to impede other clerics’ ability to have anonymous sex with otherwise consenting adults? That line of reasoning demands, I think, an especially deranged view of the clerical state and human sexuality, to say nothing of the relative importance of protecting minors from potential exploitation and abuse.

But you’re free to make your own mind up. You can read the whole story here.

Can everybody walk just away?

This week, we reported that a Vatican City court has tossed out a string of objections meant to prevent the former auditor general of the Holy See from suing the Secretariat of State for wrongful dismissal.

Many of you won’t need to be reminded that Milone was forced out of his job by Pillar reader Cardinal Angelo Becciu in 2017, and threatened with criminal prosecution for “spying” on his private financial affairs.

And I am sure most of you recall that Milone has deposited more than 500 pages of evidence with the court which, he says, proves he was forced out of his job and his reputation ruined because he discovered serious and systematic corruption at the highest levels of the curial.

And who could forget that Milone has said that, if he can’t get a hearing for his case in the Vatican, he’ll release the files to the press to clear his own name?

Well, he’s got his hearing now. After we reported on the judges’ decision and the legal arguments it raised against Milone’s case and then knocked down, I spent a lot of time this week ringing around friends close to the trial and to the Secretariat of State, taking their temperature on the whole situation.

The consensus was that while Milone probably has a case for wrongful dismissal, he definitely has the goods to back up his claims about Vatican corruption.

As judges, prosecutors, and secretariat staff have now had a chance to read what the auditor has filed, one secretariat official told me the reaction was somewhere “between fear and panic.” But, they told me, the Secretariat of State is in a bind.

If they try to buy Milone off in a bid to get him to drop the case, it would look like a coverup and leave some very uncomfortable questions and accusations lingering in the air, and in the press.

Everyone seems to agree, on all sides, that now the matter has gone to court, it has to be settled in court, and given the judges’ seal of approval. But how?

A final verdict in Milone’s favor would basically mean the judges agreed that senior Vatican figures conspired to defenestrate the auditor, his work, and the pope’s reforming agenda. This would demand a new round of criminal charges be brought against top-level Vatican brass, and probably require Milone’s files, currently deposited under seal, to be used as evidence in open court — the very thing everyone wants to avoid.

Similarly, trying to railroad Milone’s case out of court, or stall the process from reaching a conclusion, could provoke him into making good his threat to give all his files to the press — but that’s a nuclear option for Milone. Even if he manages to get back his reputation, he’d still be in the middle of a global scandal, which isn’t great for finding a new job, and it doesn’t win him back his lost earnings, either way.

One friend told me that the only way out is if everyone can walk away more or less happy with the result.

This, he said, means everyone needs to save face: Milone needs to get paid, and get an apology, and the Secretariat of State needs to be able to say it was all some kind of regrettable misunderstanding — nothing sinister. And the court needs to be able to sign off on the whole thing with a straight face.

Is this a circle that can be squared? I don’t know. But where there’s a will — and there is a will — there’s supposed to be a way, and there are some people looking very hard for it right now.

Little green men

One of the inevitable St. Patrick’s day sidecars is, of course, leprechauns.

It is not, so far as I have understood from my own visits, a commonly-held belief in Ireland that woodland gnomes dressed in green derby hats are roaming the countryside.

Though in 2017, a member of parliament there did suggest that the reason a local highway kept cratering with subsidence was because of the “numerous fairy forts in that area” and advised that “anyone that tampered with them back over the years paid a high price and had bad luck.”

And it does make for good tourist merch, I suppose.

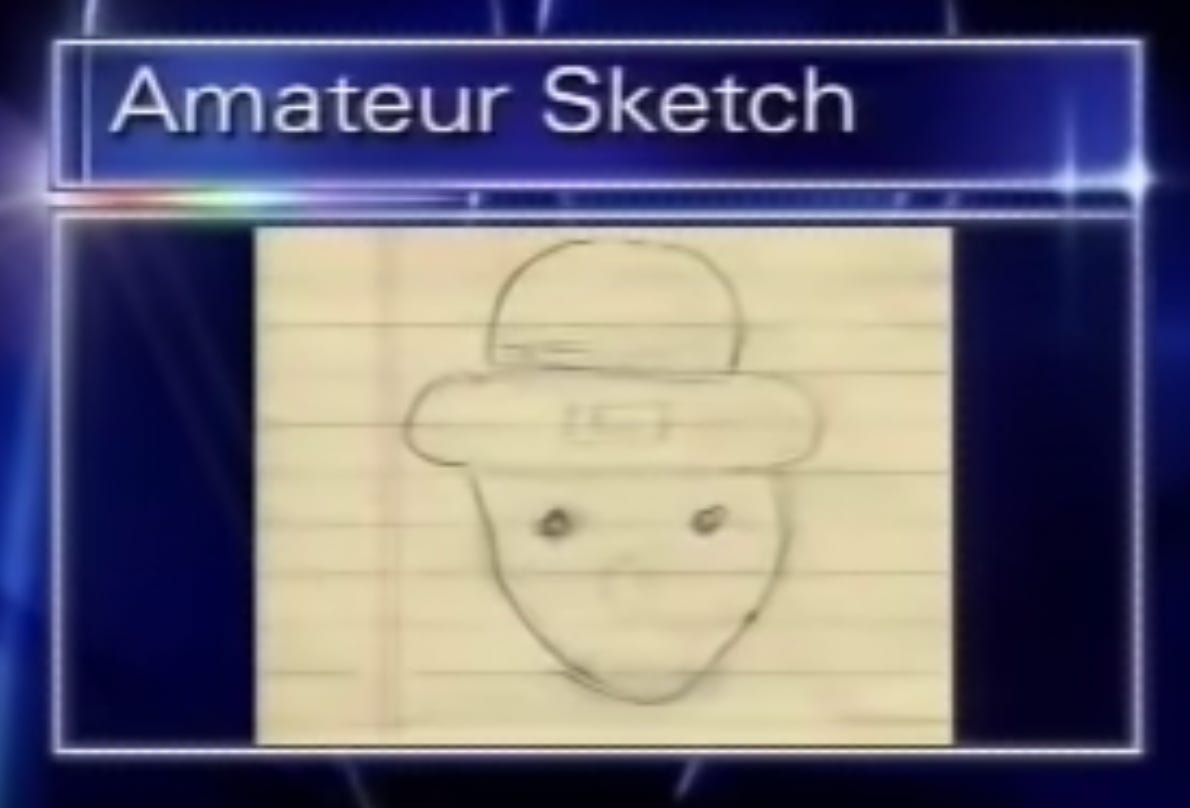

As with everything else commonly associated with today’s pageantry, leprechauns are also something of an American thing. And as I said above, there’s nothing wrong with that. American St. Patrick’s Day did, after all, give up one of the best segments in local TV news ever:

And, of course, there’s nothing distinctly Irish (or American) about the folk belief in magical little people lurking in the forest — this seems to be omnipresent just about everywhere and a baseline human superstition.

It was, for example, just last month that the president of Mexico was tweeting pictures of what he said appears to be an alux, a kind of mischievous wood elf of Mayan folklore.

And you know what? If there are actually people out there who think the forests are teeming with magical dwarves, what’s the harm?

I find it all kind of innocent, really, and mostly tongue in cheek. Especially when set against some of the insane quack-religion cons which run through the American suburbs like a spiritual opioid crisis, and which supposedly sane and educated people take deadly seriously.

If you think I’m kidding or exaggerating, you should know that the growing belief (and investment) in “healing crystals” has turned it into a billion dollar industry.

And consider the straight-faced treatment which mainstream media, culture, and increasingly even medicine give to the hilarious nonsense of reiki. Here’s what the Cleveland Clinic says about these weird people, usually in lycra or tie-dye, waving their hands over you (for a price) to make you feel all better:

The clinic, where serious doctors work, also says that reiki “fosters tissue and bone healing after injury or surgery,” and “stimulates your body’s immune system.”

Now, I am not a doctor. But I am happy to assert as a stone cold scientific fact that magic rocks and hippies’ hands don’t “deliver energy to your body,” still less heal broken bones. These people do need help though.

So, on this saint’s day, reach out to the vacuous New Ager in your life, take them for a few green beers, bond over some leprechaun chat, and then get them to an RCIA course.

See you next week,

Ed. Condon

Editor

The Pillar