Praying for the pope, an artful disclaimer, and when in Rome

The Friday Pillar Post

Happy Friday friends,

I hope you all had blessed feasts of All Saints and All Souls respectively.

All Souls and the practice of praying for the faithful departed is a serious business in our house. We have a long litany of friends and family for whose repose we pray regularly, but with special dedication on Nov. 2.

There is a real and vital relationship between us believers on earth, praying for those on their way to heaven, and those who have already made it to paradise, and are now interceding for us. But that relationship is one of those hallmarks of the faith too easily minimized or missed out altogether.

When confounding the Sadducees, who thought the resurrection of the body was nonsense, Jesus pointed out that God speaks of Himself to Moses as the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and that He is a God of the living, not the dead. My grandparents are no less alive in the Lord than the patriarchs, and I would do well to remember that.

I need to know that they, among many others, are indeed alive, and that our bonds of family love and support become more powerful, not less, once they stretch across earth and heaven.

If I find that hard to take seriously, am I really any better off than the Sadducees — and what hope do I have for my own eternal life, exactly?

We really do need to pray for the souls in purgatory, and it’s not for nothing that the Church regularly offers days of plenary indulgences that can be applied to speed them on their way to heaven.

I’ve always tried to make sure I grab every indulgence on offer, to apply to the souls of deceased family and friends. I can only imagine the bitterness and sorrow of a loved one languishing in purgatory, while they are remembered with love on Earth, but without anyone to perform the simple spiritual labor to come to their aid.

A usual condition of such indulgences is that we pray for the intentions of the Holy Father — that is, of course, not a vague reference to “whatever the pope wants.” The pope issues monthly requests for the prayers of the faithful.

Popes are often “judged harshly” and will have to render “a serious account” of their ministry to God, Francis noted, as he asked us “to judge benevolently” with our prayers and to “pray that the pope, whoever he might be – today it is my turn – may receive the help of the Holy Spirit, that he may be docile to that help.”

Francis has come under significant scrutiny, and I think it is fair to say considerable personal criticism in recent days over the scandal of Fr. Marko Rupnik, whom the pope has finally allowed to be prosecuted for the litany of abuse crimes of which he’s been accused, following an outcry of scandal at the priest’s rehabilitation into ministry.

There are real reasons to question the pope’s role in Rupnik’s case, given that quite a few people see in it a coordinated effort to shield Rupnik from justice at the expense of his victims.

To many people, myself included, papal endorsement seems the most plausible explanation for why the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith, the Diocese of Rome, and the apostolic nuncio in Slovenia would all seem to have gotten behind the disgraced former Jesuit, or allowed him to return to ministry.

But especially if those suspicions are correct, we’d do well to pray for the pope.

And we’d do well to remember, as the pope asks us to, the “serious account” to God that he will have to render for his time in office.

If many of us are convinced that there is a Franics-Rupnik connection, we should be moved to pray for the pope — both for his eventual final reckoning and that he, as Francis says, might be docile to the wisdom of the Holy Spirit in his ministry now.

That, it seems to me, is a real prayer worth making, whatever your feelings about the week’s news.

The News

The ecclesial movement Communion and Liberation has acknowledged “substantiated” accusations of sexual and psychological abuse of young adults and minors by the movement’s former U.S. leader.

Bacich was national leader from at least 2006 until at least 2013, though the movement has not confirmed the exact dates of his tenure.

The public narrative offered by the movement’s leadership is a little unclear. On the one hand, CL says that accusations against Bacich were first made in 2018 and were immediately reported to law enforcement while CL contracted a law firm to conduct an independent review, which concluded that the allegations were “based on credible evidence.”

On the other hand, they have also acknowledged that “At times, those to whom concerns were reported were slow to believe and respond to the accounts presented to them.”

So there are more questions we’re asking about the timeline.

Ecclesiastical movements like Communion and Liberation have been some of the brightest spots of evangelizing fervor in the Church in recent decades. Of course, they are very much part of the Church, and prone to the same sins and suffering as the rest of it, too.

We’ll be doing more reporting on this story. But in the meantime, pray for the members of CL, and most especially for victims of abuse.

—

A record number of Catholics formally disaffiliated from the Church in Switzerland in 2022, according to new figures published this week.

Those numbers obviously make for very grim reading, though it should be noted that they are just as bad for Protestant churches in the country. And it is fair to assume that not all of the people formally disaffiliating from the Church are doing so for entirely spiritual reasons — the Church tax is likely an influential factor in Switzerland, as it is in Germany, another country hemorrhaging Catholics.

While rates vary across the country’s cantons, in Bern, for example, the Church tax is set at 20.7% of income tax1 for Catholics.

—

Government officials warned this week that antisemitism in the U.S. has reached “historic levels” in the wake of renewed violence in the Middle East.

The U.S. bishops have condemned antisemitism repeatedly in recent years and stressed the connection between the Catholic Church and its roots in the Jewish faith and people. For one cardinal, though, this connection was deeply personal.

Cardinal Jean-Marie Lustiger, the son of Polish Jews and a convert to the Catholic faith, considered himself to be Jewish for his entire life, including while serving as Archbishop of Paris.

Lustiger had to defend his identity as both a Jew and a Catholic against those who were overtly critical of his fitness to lead the Church in France at the end of the 20th century and, as he put it, “the crucifix began to wear a yellow star.”

His is a story worth reading, and Michelle has a profile of him for you right here.

—

An Indian archbishop has denied contempt of court in a civil case sparked by an ancient Catholic community’s unique marriage customs.

Archbishop Mathew Moolakkat, head of the Knanaya Catholic Archeparchy of Kottayam, is responding to a petition filed at the high court by Justin John, a 31-year-old rickshaw driver, after the archeparchy failed to grant him a “vivaha kuri,” or consent letter, allowing him to retain his membership in the archeparchy after marrying a Catholic from outside the Knanaya community.

The Knanaya people are an ethnic group tracing their origins to Jewish Christians who migrated from Mesopotamia to India in the 4th century. As membership in the Knanaya community is determined by family lineage, Knanaya Catholics are expected to marry someone within the same community, a norm known as endogamy.

John accused both the archbishop and a local pastor of contempt of court, since a lower court in Kerala ruled in 2021 that members of the archeparchy should no longer forfeit their membership when marrying Catholics outside the Knanaya Catholic community.

This is a fascinating and complicated case, read all about it.

—

When the Vatican’s synod secretariat published a “spiritual aid” for the synod on synodality last year, the document, like much of the synod, quickly became a subject of debate.

In fact, some critics went so far as to call the document, and even the synodal process itself, “demonic.” While this might seem like hyperbole, this criticism was in response to a particular quote from St. Isaac the Syrian about having a “merciful heart” for demons.

Well, quite.

But there’s actually a fascinating history to the quote, and to St. Isaac, and a real debate to be had about whether it’s totally kosher theology or maybe a nod to the heresy of universalism.

A disclaimer

After the news last week that Fr. Rupnik’s canonical prosecution will now move ahead, my prediction, for whatever it is worth, is that it will proceed somewhat along the lines of the former Cardinal McCarrick’s case.

I expect there will be a period of relative silence from the Vatican on the subject, with any questions being batted aside with the response that since there is an ongoing legal process, further comment would be inappropriate.

Then, sometime in the next 12-18 months, the DDF will put out a short statement saying Rupnik has been laicized after being found guilty of an undisclosed number of undisclosed crimes. After that, the matter will be considered closed. I certainly never expect to see anything like a “Rupnik report” on how this case came to be such a litany of inexplicable scandals.

But what I think we can expect to see, both now and past the eventual resolution of Runik’s canonical process, is continued debate about what to do with his art, which continues to decorate churches, shrines, and even basilicas across the Western Church — and to be used by Church institutions, including the Vatican, as cover and feature artwork on publications and at events.

Some would like to see Rupnik’s famous mosaics taken down piece by piece, and his imagery banished from public Church use, out of respect for his alleged victims and understandable concern about how he is accused of using his artistic process to groom and abuse women religious.

Others have argued that separating art from artist is — and should be — something we’re comfortable doing. I have seen some argue that everyone is a sinner, and even if Rupnik is a terrible sinner, that doesn’t negate the beauty of his work and the spiritual edification it has brought to many.

At the risk of being considered a philistine, I have tended toward the former argument.

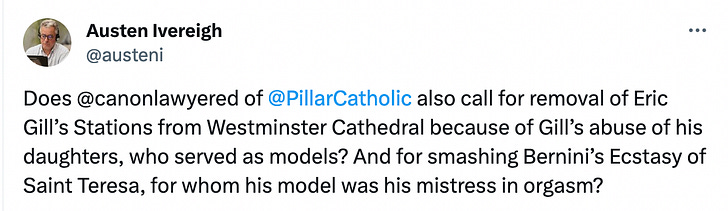

Then again, Austen Ivereigh, a synodal assembly member and quasi-official Vatican spin doctor, has previously argued against me on this point.

Ivereigh went so far as to compare Rupnik’s work to that of Eric Gill, the English sculptor whose Stations of the Cross remain in Westminster Cathedral despite Gill’s daughter accusing him posthumously of both incest and bestiality.

I confess, I am not sure that appealing to the example of a man who abused his own children and the family dog is a winning argument for Rupnik, though Austen seems to think it is.

But if people will insist on championing the merits of art for art’s sake, over and above the crimes of its creators, I’d propose a simple solution that, I hope, might work as a compromise.

It seems to me that the greatest argument for the removal of Rupnik’s work, and its discontinued use as a source or focus for spiritual devotion, isn’t that it is tainted by the general scandal surrounding Rupnik.

Rather, it is that his victims have spoken at length and in heart-wrenching detail about how he sexually abused them specifically as part of the creative process for producing his pieces of “art.”

Thanks to the world of animal rights advocates, for decades all films have ended with a discreet disclaimer that “no animals were harmed during the making of this motion picture.” It’s something you’d hope wouldn’t have to be said, but there we are.

Could the custodians of some of Rupnik’s major pieces not display similar disclaimers where appropriate?

Taking as an example, here in Washington, D.C., the National Shrine of St. John Paul II features an especially prominent and famous Rupnik mosaic in its chapel. Surely the shrine’s custodians, the Knights of Columbus, would be willing to display a written assurance that “no religious sisters were abused in the making of this mosaic.”

It doesn’t seem like a lot to ask, and I’m sure they could find a tasteful way to do it.

Of course, if custodians of Rupnik’s work find themselves unable to say with confidence that their sacred spaces weren’t decorated through acts of sexual abuse of women religious, they might want to think about that, and how sacred a space they’ve really got.

And, since you’re reading Austen, I’d say the same about Eric Gill.

When in Rome

When I was a kid in England, our local parish priest was something of a dark horse. Despite being the picture of a cherubic elderly Irish cleric in a sedate little parish, he was a surprisingly well-traveled and well-connected man.

Bishops from all over the world would stop by his rectory for a weekend on their way to or from their ad limina visits to the pope, just to check in with Fr. Barry. He’d sometimes outsource their feeding and entertainment to my family.

One of these visits I remember better than most. The visiting bishop was from a Caribbean island and, in addition to being a youthful convert, he’d been a very late vocation to the priesthood, going to seminary after becoming a widower at a not-very-young age.

As a young teen, close proximity to a bishop was still a novelty for me, his biography was obviously fascinating, and he was still new enough in the role that the shock of his own appointment hadn’t worn off. But he didn’t talk to me about any of these things, really. What I most clearly remember him saying was “Pray for the dead.”

“You have to pray for them, all of them, in purgatory,” he told me, “it is such an important responsibility we have, and we think so little of it.”

He went on to talk about the tragedy, as he described it, of Protestants who don’t know or believe in the importance of praying for their dearly departed. This, he told me sitting in our living room after dinner, wasn’t something which we should feel superior about, but that it created what he called a “terrible responsibility” for us to pick up the slack and remember in our prayers those other Christian souls who have died.

I think I must have been 12 or 13 at the time, and it was probably my first real encounter with the concept of ecumenism, and it remains probably the most profound thought I have heard on the subject.

He gave me a holy card with a simple prayer for the souls of the faithful departed and bid me to remember the souls of all Christians, especially those with no one to pray for them.

Tribal bickering and snark are easy temptations to give into, of course. And the memory of the bishop’s words came back to me this week when an American couple went sort of viral on Twitter when they posted pictures of themselves on vacation around the Vatican.

The pair of American evangelicals decided to tour the Vatican in matching Martin Luther T-shirts to mark “Reformation Day” on the eve of All Saints. Bless their hearts.

As sectarian stunts go, I’d put this at the shallow end of the creative pool, but a lot of people online got very het up about it.

I’m not especially surprised, though others apparently were, that the gendarmes allowed them into St. Peter’s with their shirts. Though I do think the man should have been cautioned for wearing shorts in a church, or in a city at all. And he should probably be arrested for the crime of wearing white shorts in October.

But we should really be moved to pity and charity for these people, rather than anger. The kind of American tourists who go around European cities wearing matching T-shirts need our prayers.

And the kind of Christian who can stand amidst the grandeur of St. Peter’s, above the very tomb of the prince of the apostles, and think primarily in terms of online prankery should move us to empathy, more than anything else.

So spare a prayer for the Buices, and maybe say a whole rosary for their departed relations, because I doubt anyone else has.

See you next week,

Ed. Condon

Editor

The Pillar

When this newsletter first went out, I wrote 20.7% of income, not income tax. My mistake and my thanks to the reader who spotted it.

The best argument for destroying his art is that his art is objectively awful.

Let us never forget the Mercy Monster, which haunts me to this day.: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/5/50/Jubilee_of_Mercy_logo.jpg

While it pains me to agree with Austin Ivereigh, I think he's (mostly) right on the merits. Consider the case of Thomas Cranmer. Cranmer is unquestionably the most influential apostate and heretical cleric of the English Reformation (revolution). His enduring work of art and spirituality is the Book of Common Prayer. Yet we find today in the Masses of the Ordinariates of the Anglican patrimony created by BXVI (such as the Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter in the US) prayers directly from the BCP! As GK Chesterton said:

"But why has the old Protestant Prayer-Book a power like that of great poetry upon the spirit and the heart? ... It might be put in a sentence; it has style; it has tradition; it has religion; it was written by apostate Catholics. It is strong, not in so far as it is the first Protestant book, but in so far as it was the last Catholic book. ... Let anyone recall for himself the very finest passages in the Book of Common Prayer, and he will soon see that they are concerned specially with spiritual thoughts and themes that now seem strange and terrible; but anyhow, the reverse of common; ... "in the hour of death and in the day of Judgment.” Who talks about the hour of death?"

Despite his best efforts at being an apostate, Cranmer spoke some Catholic doctrine perhaps more beautifully than any English writer ever has. Are we wrong to incorporate that beauty into the Catholic Church because it was spoken by such a great heretic?

All that being said, there is a simple reason for getting rid of Rupnik's art that has been pointed out by others. It's ugly. Ed also makes a compelling point that if his sexual escapades were incorporated into the creation of the art itself, that is...disgusting and probably changes the calculus.