Happy Friday friends,

As you may have seen, we at The Pillar launched a shiny new website this week. It’s been a long labor for us — and by “us” I mean mostly JD — but it's finally here.

In the little more than a year-and-a-half that we have been going, we have (to my surprise) published thousands of stories, newsletters, and podcasts, and we simply outgrew the site we were using.

I hope now everything will be a little more navigable, a little easier to search, and a little easier on the eye as well. If you were a subscriber at the old site, you’re still a subscriber — you don’t have to do anything, although if you want to comment here on the new site, you might need to log in again, but that process is pretty intuitive.

Getting the new site up has been the big project standing in the way of us launching a bunch of other stuff we have been dying to get off the ground. Now that it’s done, you can look forward to some new offerings from us shortly. More on that soon.

For the moment, I hope the digital facelift meets with your approval. And please bear with us through the inevitable teething troubles over the weekend.

And, of course, thank you to our subscribers. This new site, and all of the content on it, happen because a relative handful of our readers think what we are doing is worthwhile enough to support.

Our spanking new shopfront notwithstanding, our business remains the same — we are running a newsstand with an honesty box here. No one has to pay to read our reporting and analysis — we want to keep it that way for the people who can’t afford the $5 a month.

Among our favorite emails are the ones we get from men and women who tell us they are canceling their subscriptions because they are entering seminary or religious life and no longer have a disposable income, but with promises to keep reading and to pray for us.

When you sign up as a paying sub, you’re helping keep our reporting free for people like them.

The News

The consistory of the College of Cardinals has ended without a papal resignation, the appointment of a “vice-pope,” or any of the other dramatic predictions which were swirling around Rome last week. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t something big going on.

Pope Francis called the consistory to talk about his new curial constitution, Predicate evangelium, published earlier this year. And for many of the cardinals, that topic meant talking about lay governance.

Praedicate’s marquee reform is the explicit statement that a lay person can lead a curial dicastery.

Now, to a degree, this has always been possible, at least for some departments. Nothing other than convention has ever stopped a pope from naming a layperson to run, for example, the Pontifical Academy for Life.

But the big question for the cardinals is about limits.

Which departments can’t a lay person lead? The Dicastery for Culture and Education? For religious life? What about bishops, clergy, or doctrine? Praedicate doesn’t answer this, though it acknowledges that there are limits, at least in theory.

The limits matter a great deal — they go to the heart of the Church’s ecclesiology, her sacramental theology, her self-conception, and self-definition.

How intrinsically linked is the governing authority of the Church to the sacramental power of ordination?

Theologians and canonists have been arguing the toss over that for literal centuries, and it culminated in Vatican Council II’s dogmatic constitution Lumen gentium, which re-emphasized the essential unity of governing authority and sacramental power.

But nearly 60 years later, the debate has reopened, and different cardinals are weighing in. What they think, and how far Pope Francis decides to go with the idea of lay governance, will affect every part of the Church’s life, from the Vatican, to the German “synodal way,” to chancery appointments in U.S. dioceses.

The Indiana Supreme Court has upheld the dismissal of a high school teacher in the Archdiocese of Indianapolis, who was fired in 2019 after he contracted a same-sex marriage.

The teacher dismissed by Cathedral Catholic High School entered a civil marriage with another man, who was also a teacher at a Catholic school in the same archdiocese — Brebeuf Jesuit Preparatory School.

In 2019, Archbishop Charles Thompson told both schools not to renew the teachers’ contracts, saying their state of life was in obvious contradiction to Church teaching. Cathedral complied, Brebeuf refused. Thompson revoked Brebeuf’s right to call itself a Catholic school, and the Jesuits appealed to the then Congregation for Catholic Education.

Since then, Thompson’s decree has been suspended while, in theory, the now Dicastery for Education and Culture considers the case. In practice, as we’ve previously reported, Rome asked Thompson’s predecessor in Indianapolis, Cardinal Joseph Tobin, to try to broker a truce between the archbishops and the SJs, but apparently without a result.

The Indiana court decision might move things along. The Vatican wouldn’t want to announce any kind of decision or compromise over Brebeuf which could have been used to undermine Thompson’s civil court case over Cathedral. That risk has now passed. But I am not holding my breath for a result anytime soon.

The Dicastery for Education is currently headed by Cardinal Giuseppe Versaldi, under whose leadership the dicastery has put out several recent documents on Catholic schools and education which would suggest to me that he might, all things being equal, lean towards Thompson in the Brebeuf dispute.

But here’s the thing: Versaldi is 79 years old and almost sure to be replaced in the next few weeks — probably by a layperson. So my money is on no resolution being announced until there is a new prefect at the dicastery, and until that prefect has their feet well and truly under the desk and made the department their own.

You can get up to speed with the whole situation here.

When the Shrine of Mary, Mother of Persecuted Christians, is blessed in London next week, it will be an historic moment — it is thought that it will be Europe’s first shrine dedicated to prayer for believers currently suffering for their Christian faith.

“In August 2014,” he told Luke, “I was a parish priest in Stowe, Vermont, and I heard that for the first time in basically 2,000 years, there was no Mass being said in Mosul. Mosul is Nineveh, where Jonah’s tomb was before ISIS blew it up. I just remember thinking, ‘How can we help? How can we assist?’”

It’s a fascinating story. Read the whole conversation here.

Shortly before opening last weekend’s consistory, Pope Francis had a meeting with Fra’ John Dunlap, the Lieutenant of the Grand Master of the Order of Malta, and with his delegate to the knights, Cardinal Silvano Tomasi.

We don’t know what they discussed, but it seems safe to assume the pope was letting them know he’s about ready to make his final decision on the constitutional future of the order — and he’s due to meet with them and other senior knights again tomorrow.

Sehnaoui’s letter was, by turns, scathing and deeply sad as he addressed recent moves to restructure the order’s leadership, presumably ahead of a Chapter General to ratify whatever reforms the pope decides upon for the knights.

We talked to Sehnaoui about his sense of “shame” at how the constitutional reforms have been going, and what he sees as the prospect that the order as it’s been for nearly 1,000 years is about to “dissolve.”

Archbishop Vincenzo Paglia, president of the Pontifical Academy for Life, made headlines — again — after he told a journalist that a 1978 law decriminalizing abortion is a “pillar” of Italian “social life” and is “absolutely not” up for discussion in the country.

The academy has since tried to walk the comments back, claiming that Paglia merely meant to recognize that abortion was a settled fact of Italian law, not suggest he approved of it. His point, they suggest, was that such a settled law doesn’t really factor into election calculations.

And some sources in Rome say those statements are part of a well-devised strategy, aiming to culminate in a papal reference to the subject in the aftermath of the synod on synodality.

As one theologian close to the Vatican thinking on all this told us: “Within one year-and-a-half, we will see something - a footnote, perhaps - that relativizes Humanae vitae to the realm of the conscience. That’s what they’re working toward.”

That doesn’t sound too outlandish a prediction to me, at least going by what the Pontifical Academy for Life has been saying lately.

For myself, it seems ironic that as our society watches the basic concepts of identity, family, and human dignity actively dissolving in a caustic soup of ungendered mass sexuality, there are people in the Church who want to relitigate the document which predicted virtually all of the worst consequences of the last 50 years.

Anyway, you can read JD’s whole analysis here. And you should.

Believe it or not, one of the things I get the most requests for more coverage of is “integralism,” a political philosophy that’s having something of a moment these days.

I get a lot of emails asking us either to support the premise that the Church’s jurisdiction over religious matters transcends the state’s own authority in the civil sphere — or to denounce the intellectual movement as an apologia for theocratic authoritarianism.

But as I’ve said before, it doesn’t matter what I think. If you want to hear about integralism, let’s hear about it from the people who spend a lot of time thinking about it.

This week, Charlie Camosy spoke with two people highly qualified to talk about the subject, and who come at the idea of integralism from very different perspectives.

He spoke with Charlie about the proper relationship between Church and state in the Church’s own teaching, and the need to understand how this plays out in different times and places, under different kinds of government, and in different societies.

He also dispelled some myths:

“One objection is that integralism is nastily authoritarian. It is committed to defending everything done in the past by the Church and by the Catholic state at her behest – such as the inquisition and its methods or the terrible laws governing relations with the Jewish people. But integralism is not about defending this…

The Church’s integralist teaching matters – though not as a program that prioritizes political action over evangelization. Trying to bring back the Catholic state without a reconversion of the people is just not possible.

Integralism reminds us instead what loss of faith at the level of the political community will cost.”

Read the whole conversation with Thomas Pink here.

—

On the other side of the conversation, Charlie also spoke with Bill McCormick, S.J., visiting assistant professor of political science and philosophy at Saint Louis University, and the author of “The Christian Structure of Politics: On the De Regno of Thomas Aquinas.”

“Integralism has too often been criticized in a question-begging manner, namely for not being liberal or democratic. But there are a great many Catholics who would agree with [its basic] propositions and still not be integralists.

For thinkers like Aquinas, it’s the need to affirm the transcendent that makes integralism too akin to civil religion… Indeed, for Aquinas, the threat of civil religion is a pressing concern in De Regno: the subjection of religious authority to political power.

Most Christians in most times have been deeply attached to a regime form, whether monarchy for much of history or democracy today. A great temptation of any Catholic ‘post-liberal’ project is to replace one ideological attachment for another.”

You can read McCormick’s back and forth with Charlie here.

I hope you read them, and find them interesting and thought-provoking.

Most of all, I hope you read them together, so the next time you see the people throwing the word “integralism” around, you have some context from both sides.

The Archdiocese of St. Louis said this week that students will not be without school lunches in Catholic schools, despite its recent decision to stop participating in federal school lunch and milk subsidy programs for students from low-income families.

The archdiocesan spokesman cited unspecified federal mandates tied to the money, and said “with any federal subsidy, schools that participate in these programs are subject to a wide variety of federal mandates, which could ultimately impact decisions concerning admissions, extracurricular activities, facilities, and logistics.”

We took a look at some of the possible explanations for the decision, which, as one senior Catholic in the state told us “seems confusing at the ground level — it doesn’t seem like the kind of thing Archbishop Mitchell Rozanski would be the first [bishop] in the country to do.”

Lost knowledge

If you have been reading these newsletters for a while now, you know that from time to time, I like to nerd out about space stuff. I’m going to do that now.

But bear with me on this one, because I am going somewhere.

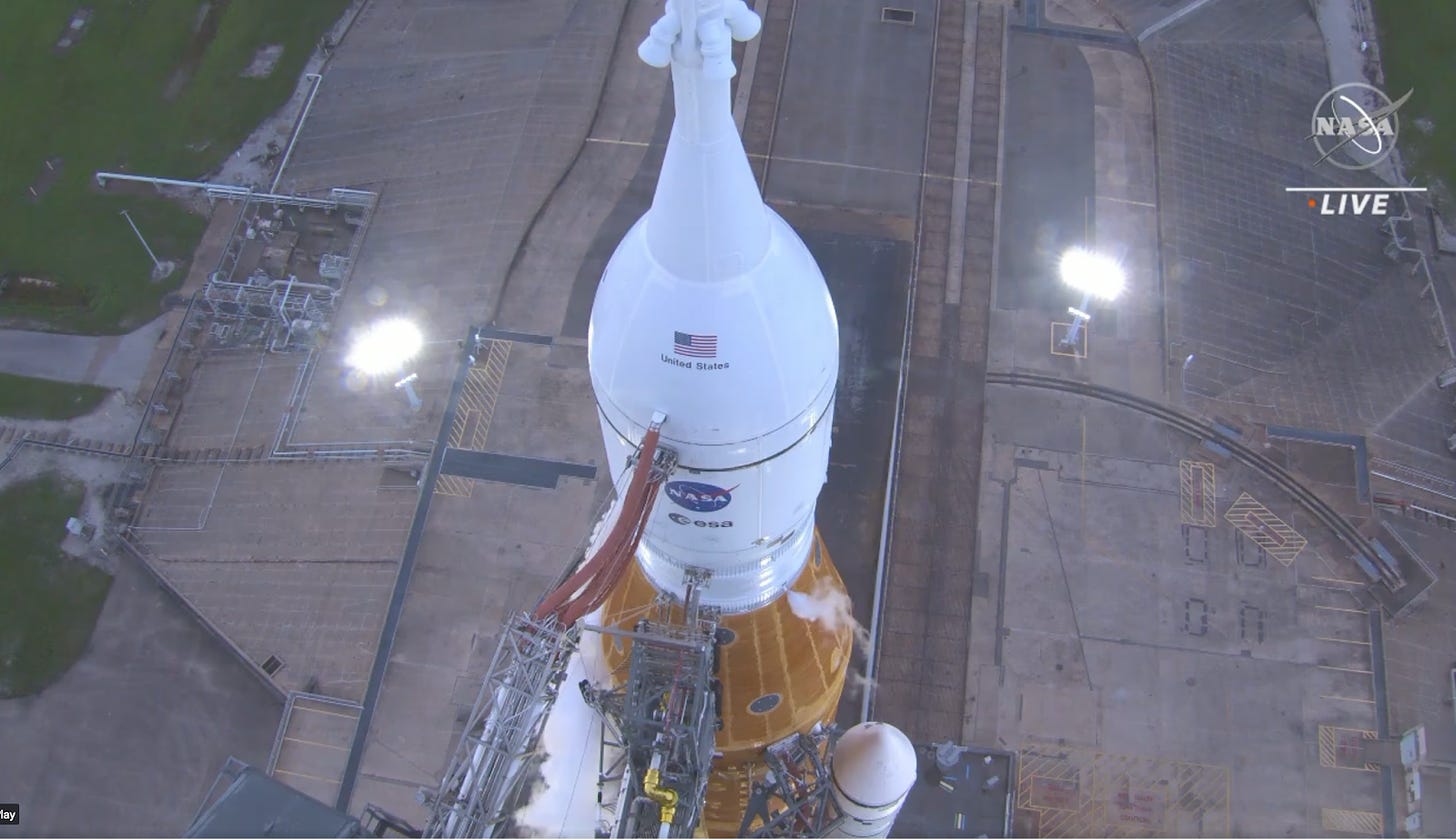

On Saturday, Artemis I is scheduled to launch from Cape Canaveral shortly after 2 p.m. It’s the first mission of the Artemis program, which will eventually return people to the Moon, for the first time since 1972.

The unmanned mission was meant to lift off on Monday, but had to be scrubbed after a bad temperature sensor was detected on the rocket system, just before launch.

Artemis is expected to spend six weeks in space, performing what they call in the space game a “trans-lunar injection” — it’s going to fly to the moon, basically, which isn’t all that simple when you consider that the Earth is revolving around the Sun at about 67,000 miles per hour and the moon is going around the Earth at another 2,300 mph.

Once there, Artemis’ (unmanned) Orion spacecraft will deploy 10 small satellites, and then fly in low orbit around the Moon for six days before returning to Earth.

Artemis II, scheduled for 2024, will take a manned crew into lunar orbit, and Artemis III will, God willing, bring people back to the lunar surface in 2025, with subsequent missions planned out after the moon landing.

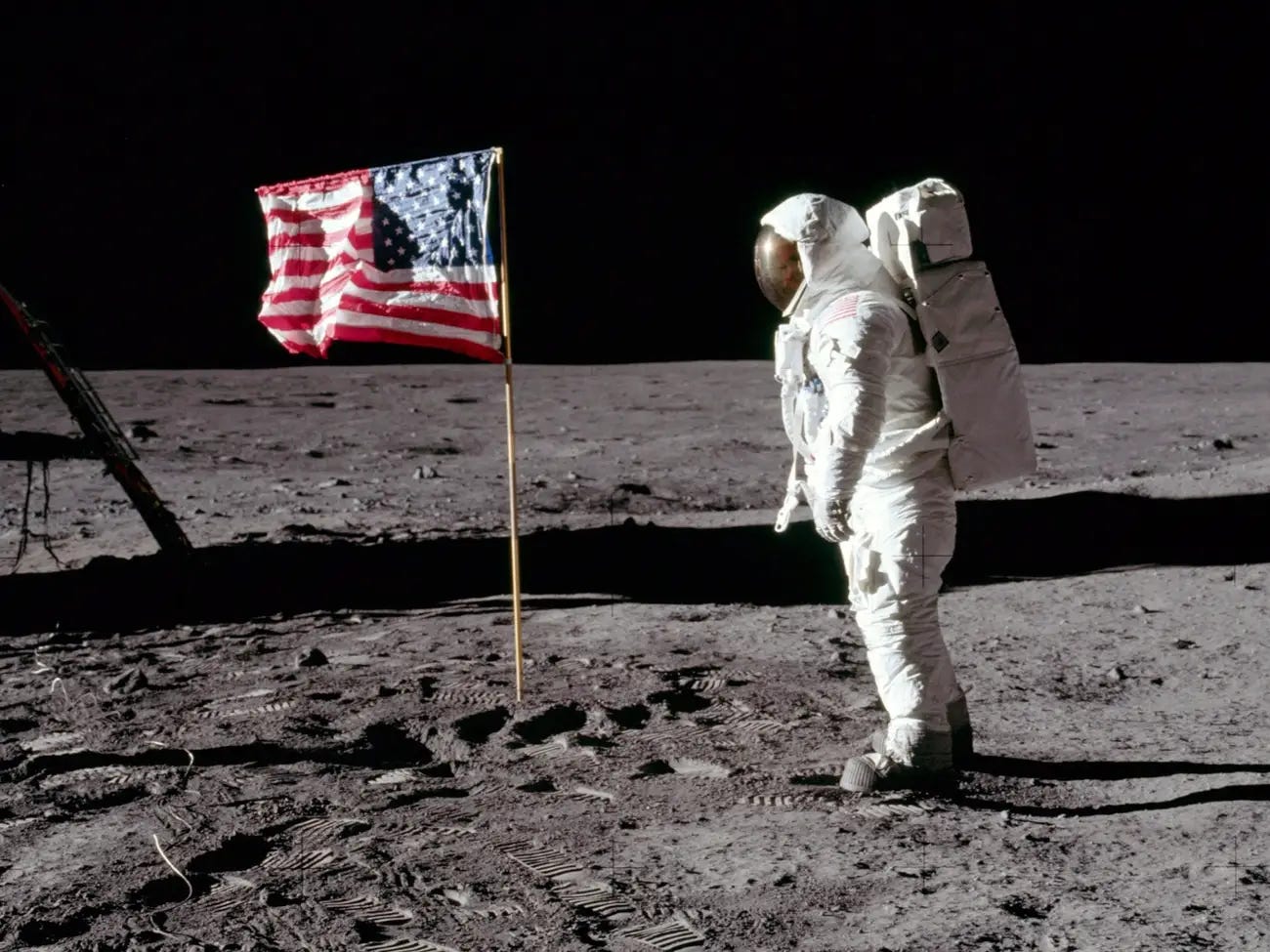

This is, and I cannot stress this enough, a big deal. But most people don’t seem to think so. I have tried to get a lot of people excited about this — most respond with some version of “Didn’t we go to the moon already? Why do we need to go back?”

The reason it’s such a big deal, and the reason we need to go back is because — believe it or not — we don’t know how to do it anymore.

We knew how to get to the moon 50 years ago, for sure. And there are lots of reasons why we stopped going, budget constraints and loss of political will chief among them.

But how, you might ask, could we forget how to do it? The moon landing is the crowning achievement of our human endeavor!

It’s actually pretty easy.

For a start, we simply don’t make the technology and the hardware we used to use. And in a lot of cases, we don’t even make the materials we used to make them. The entire industry of design, manufacture, and assembly of the Saturn rocket systems, which took the Apollo missions up, has been so comprehensively disassembled that we probably couldn’t build a new Saturn rocket if we tried.

But the real loss has been in human knowledge.

Flying people to the moon and back means understanding and using the equipment in ways that no blueprint could account for, or preserve for replication. The same goes, believe it or not, for the math.

You might think that blasting a rocket off from Florida, taking it into orbit, punching it out to the moon, landing it on the surface, and then bringing the whole thing back again is one giant plug-and-play algebra problem. But you’d be wrong.

Running the numbers for a lot of these missions is mind-breakingly complicated in theory. In practice, where things don’t weigh what the spec sheet said they would, or perform exactly as planned, the uncomfortable truth is that moon landings are a lot closer to art than science — they’re a kind of living process. And guess what? In the past 50 years, almost everyone who had that knowledge has retired, died, or just plain forgotten.

So what Artemis is doing, almost literally, is reinventing all the wheels that we need to get us to the moon.

The fact that we used to know how to do this doesn’t diminish the significance of the undertaking, but it should make us acutely aware of how lightly we hold all our accumulated knowledge and progress.

We tend to think that once we know something, it’s known. The knowledge just sits there, on a shelf or a server in California, and anyone can just pick it up. But that’s not exactly right. Knowing, no less than learning, is an active state. We have to keep the knowledge of what we have learned alive, or we will again cease to know it in any practical sense, however hard we fought to learn it in the first place.

This lesson holds for our understanding of the natural law and ecclesiology, as much as for rocket science.

If we find the great questions of 50 years ago are being asked again, questions we all knew to be answered truly by Lumen gentium, or Humanae vitae, or Apollo 11, we don’t have the option of simply saying someone already solved that problem.

If we value those achievements, then we have to do the math all over again, offer the solution again, and accomplish the same work again in our time. That’s the mission.

See you next week,

Ed. Condon

Editor

The Pillar