Portuguese President Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa signed a euthanasia and assisted suicide bill into law last week.

Portugal now seems set to join other Western European countries such as Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg, which have had legal euthanasia for several years, and neighbouring Spain, which legalised the practice in 2021.

But the law isn’t in force yet, and opposition from the medical and political establishment — including the president — could yet cause it some problems.

—

Parliament passed the law on May 12, with the bishops of the country calling it “a serious threat to the value and dignity of human life,” and Pope Francis lamenting that “[As] we celebrate the memory of the apparitions of the Virgin Mary to the little shepherds of Fatima, I am very sad, because in the country where Our Lady appeared, a law to kill has been enacted.”

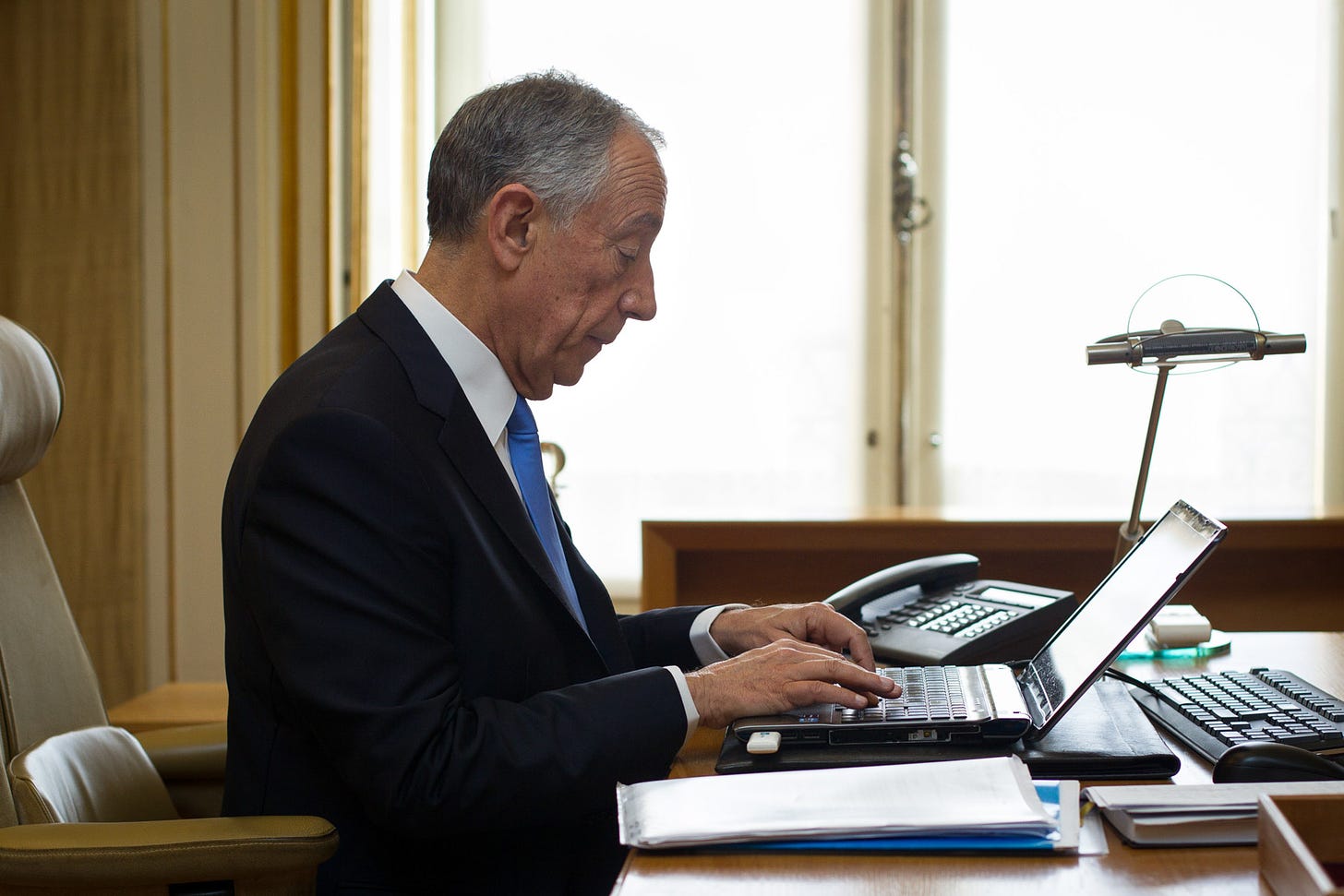

Rebelo de Sousa, a practicing Catholic and avowed opponent of the law, added his presidential signature on May 16, appearing to bring to a close a drawn-out conflict between him and parliament’s governing Socialist Party, which began in 2016, when dozens of public figures, including leading politicians, signed an open letter calling for legalization of assisted suicide and euthanasia.

The Socialist Party proposed a bill in 2017 which was discussed over the following year and a half, and voted on in 2019, failing by five votes.

Left-wing members of parliament – with the notable exception of the Portuguese Communist Party, which has consistently voiced its opposition to euthanasia – then brought the subject up again in 2020.

That time it gained enough votes to be approved, but the president – four years into his first five-year term – came up with a means of spiking the legislation, sending the bill to the Constitutional Court, asking the judges to rule on the law’s use of the phrase “permanent and serious injury”, which they found to be too vague.

Parliament then rushed through another, amended version of the law, which the president vetoed. Normally, if Parliament approved the bill again, the president would constitutionally be forced to sign it into law. But since the legislature was just days away from being dissolved for a general election, he was able to effectively pocket-veto the bill.

The whole process then began again from scratch after elections which returned a left-wing and pro-euthanasia majority.

A fourth attempt to legalize euthanasia was again sent to the Constitutional Court. This time, Rebelo de Sousa, himself an expert in constitutional law, asked the court to look at the definition of suffering which would allow a patient to request euthanasia or assisted suicide.

The judges considered the phrase “physical, psychological and social” suffering and again ruled it was unconstitutionally vague.

Finally, a new version of the law was approved and sent to the president, who this time decided not to forward it to the court, but instead returned it to parliament, asking to clarify certain passages. Crucially, however, he said that should the members of parliament return the law to him unchanged, he would sign it. He did so last week.

Many anti-euthanasia activists have been critical of the president’s apparent capitulation, accusing him of backing down after years of struggle.

José Maria Seabra Duque, a lawyer who is vice-president of the Portuguese Pro-life Federation said “unlike many others, I not only have deep respect for the president, but I am grateful for all he has done in this process. But we are disappointed, of course. We don’t understand how a law like this, which regulates state-administered death, could enter into force without ever having gone to the Constitutional Court.”

But was Rebelo de Sousa finally out of moves, could he have done more to halt the incoming law again, or might he still be working on a plan?

Constitutional law expert Paulo Otero insists that the president could simply have refused to sign the bill, even though the Constitution would seem to leave him no choice.

“It would be unprecedented, but the president cannot be the only citizen in Portugal who does not have a right to conscientious objection,” Otero told The Pillar. “All elected officials have a right to conscientious objection, and he could have exercised this right if he had wanted to”.

But even though it seems like the euthanasia lobby has won the day, Rebelo de Sousa may still have a couple of cards up his sleeve.

A source very close to the president told The Pillar that he could still make life very difficult for the Government, with whom he is in open conflict over different political matters.

Once a bill has been signed into law it has to be regulated by the Government. If the Government opts to do so through an executive decree, Rebelo de Sousa could influence the process by raising objections and making suggestions, trying to limit the law’s scope. It could also slow the process down considerably.

As a matter of procedure, laws have to be regulated within 30 days of their enactment, but there are no consequences for not doing so, and in practice some bills languish for years before coming into force.

The Government can work around this by regulating by ordinance, which does not require presidential involvement, but that would leave it open to other legal challenges and complications, as well as creating a PR headache for Prime Minister António Costa who would likely be criticized for acting in an untransparent way, at a time when his government is already under fire in the press.

Meanwhile, both the president of the Autonomous Region of the Madeira Islands and a group of center-right MPs have announced that they will be asking the Constitutional Court to re-examine the whole law.

One influential lawyer involved in anti-euthanasia campaigns in Portugal told The Pillar that there is “no doubt that these decisions to ask the court to examine the law were coordinated with the president.”

“He decided not to do so himself this time, knowing that somebody would do it for him. The president likes to strategize, and this is a clear example, although it doesn’t always work out the way he expects”, said the lawyer who asked not to be named because they are not authorized to speak about the presidential administration’s tactics.

But while the court will examine the law once it receives the formal requests to do so, the legislative process is not suspended while the judges deliberate, so the law could still enter into force after being regulated, before a final judgement comes through.

Ten of the 13 judges on the Constitutional Court are nominated by parliament, and only a select few will be chosen to weigh in on the matter, so the makeup of the review panel and their final decision is still up for grabs.

“I hope that the court will understand that our constitution says that human life is inviolable. I don’t think it could be clearer than that, and I don’t know what else the law needs to say for euthanasia to be forbidden”, Paulo Otero told The Pillar.

—

Defiant doctors

Another potential hold-up for euthanasia law could come from the bill’s creation of a five-member Evaluation and Verification Commission (EVC).

The Supreme Judicial Council, the Public Prosecutor, the National Ethics Council, the Nurses’ Guild, and the Doctors’ Guild are all requested to name a member to sit on this commission. At least one of these organizations, however, has said it will not comply.

The Doctors’ Guild, a secular organization that represents all physicians in the country and regulates most aspects of the profession, has long been opposed to the introduction of a euthanasia law, and its newly-elected chairman has said he will maintain the commitment of his predecessors to not cooperate with it in any way.

This position comes as no surprise to José Diogo Ferreira Martins, president of the Portuguese Catholic Doctors Association (CDA), and secretary-general of the World Federation of Catholic Medical Associations (WFCMA).

“We fully understand his position. Euthanasia is not a medical act, and therefore the chairman of the guild couldn’t very well name someone to a commission that doesn’t concern them.”

Ferreira Martins said while he wouldn’t hazard a guess as to how many doctors will declare themselves conscientious objectors because he doesn’t have sufficient data to do so, based on his own experience working in public hospitals, he expects that most of his colleagues remain opposed.

“If we look at the past seven chairmen of the Doctors’ Guild, all of them, without exception, came out against euthanasia, and in the last elections, if I am not mistaken, out of six candidates only one said he was in favor of the law.”

The head of the Catholic Doctors Association said the law represents another attack in a series on the conscience rights of doctors.

“The right to conscientious objection is one of our greatest concerns at the moment, not only for the (CDA), but also for the WFCMA. We had a meeting today with the Dicastery for the Promotion of Integral Human Development and we expressed just that. They took note and said they share our concern. This is not just something we are worried about, it’s a problem for the whole world”, he said, during a phone interview from Rome.

But even if the Doctors Guild refuses to nominate a representative for the Verification Commission, however, this may have little more than a symbolic effect.

“In theory, the commission would only be formed once it had all the members required by the law. However, the law sets a date for the commission to be formed, which was obviously included as a workaround because of the refusal of the Doctors Guild, and which flies in the face of good administrative procedure,” said Seabra Duque.

“You can’t have a law that says that there will be a commission formed by a certain number of people, and then have it take effect without that number of people. Especially for an issue such as this.”

But, while some pro-euthanasia politicians and activists have already said that the doctors will have to comply with the law, which mandates that they name a representative, constitutional expert Paulo Otero said that the state cannot impose its will on the medical class on this issue.

“The state can’t define the ethical standards of the medical profession. These are defined by the members of said profession, and in this case, they are international standards,” he told The Pillar. “The state can’t interfere, it has to respect those limits, and it can’t impose as legitimate something that those international standards consider ethically illegitimate.”

Otero also pointed out that the law bans conscientious objectors from sitting on the CEV. “This is a clear case of discrimination,” he said. “Why should the exercise of a fundamental right, as is conscientious objection, lead to the denial of another right?”

—

The Doctors’ Guild is not the only professional organization to come out against the law.

Over the seven years and five different bills already discussed, parliament repeatedly requested and then ignored the expert opinions of the Lawyers Guild and the Portuguese Ethics Council, both of which have criticized the law, and crucial aspects of it.

Maria do Céu Patrão Neves, current president of the Portuguese Council of Ethics for Life Sciences, told The Pillar she is disappointed that none of the organizations’ opinions were taken into account, and pointed out major flaws in the current law.

“The law says that all those who request euthanasia should have access to palliative care. But in a country where only 30% of those who need palliative care do have access, this poses a serious risk. Will we have people who asked for euthanasia being given priority access to palliative care, over those who didn’t?” she asked.

“We could even have cases of people requesting euthanasia just to get access to palliative care, and then say they changed their minds. This [whole process] is open discrimination and abuse.”

“Another thing that is also quite serious is that euthanasia is supposedly being legalized out of respect for personal autonomy,” Patrão Neves said. “However, all throughout the process, the real power is in the hands of the doctor, to the point that it is the doctor who gets to choose and/or authorize who can be present in the room at the moment of death.”

“The patient can say who he or she would like to have there with them, but the doctor has to sign off on it. This is nonsensical, and a lack of respect for the patient”, the head of the Ethics Council said.

Patrão Neves also said she worries that politicians are getting into the habit of asking for expert opinions only because they have to, but with no intention of paying attention to what the experts have to say.

“The members of the council have a wide range of ideological and philosophical sensitivities, as well as a wide range of academic, scientific, and professional qualifications. It is almost a microcosm of society, which is why we think that the recommendations of the council merit greater attention from legislators.” But, she said she is “surprised, to say the least, that the major ethical issues highlighted by the council, which were the result of a consensus among its members, were ignored.”

This behavior on the part of Parliament comes as no surprise to the Pro-Life Federation. “It has become clear that the law and good practice mean little to pro-euthanasia politicians so long as they manage to get their way”, said José Maria Seabra Duque.