Pillar subscribers can listen to JD read this Pillar Post here: The Pillar TL;DR

Hey everybody,

Today is the 9th of July, and you’re reading The Tuesday Pillar Post.

Some of you, like me, are also preparing to head next week to the National Eucharistic Congress, the capstone event for four pilgrimages which have been traversing the country this summer with the Holy Eucharist, spurring processions in cities across America.

The Congress started out as the main event of the USCCB’s three-year Eucharistic Revival project, meant to spur more devotion among Catholics in the Blessed Sacrament.

But from where I sit, the pilgrimages across the country have become the main attraction, as tens of thousands of Catholics have participated in the local processions that make up the pilgrimage.

There will be, though, some 40,000 Catholics at the National Eucharistic Congress next week, and The Pillar’s team will be among them.

Now, to be sure, there are numerous practicing Catholics, some Pillar readers among them, who have said they’re not going to the congress because it wasn’t financially feasible for them, even with scholarships offered, or because they weren’t sure whether the programming would be right for their kids. And there are some who said they won’t be there because their own dioceses haven’t done much to organize a trip.

But to their credit, at least from where I sit, congress organizers have pretty consistently referred to their own efforts as a “learning experience,” and acknowledged that communications and logistics have been ambiguous at times. And also to their credit, I’ve noticed that congress organizers have been pretty responsive to public feedback, including The Pillar’s own coverage of issues — giving me the impression, at least, that the congress team really has aimed to organize an accessible, fruitful, meaningfully Christian experience for the Church in the U.S., and has been willing to listen.

I say this because as the congress gets closer, I’ve noticed more frequently sharp rebukes and jabs from critics of the entire Eucharistic Revival project. A few of them are worth considering, but most seem like partisan-fueled gnat-straining of the worst kind.

And, look, working to organize the Eucharistic Congress is no easier than any other task in the Church — and ecclesial laborers, lay and clerical, all know the emotional toll of working like hell at something, with limited budget and little pay, only to watch people on the sidelines show up to cluck and sneer at your good faith efforts.

So whether you’re going or not — and whatever you think could have been better — let’s pray for the organizers of the Eucharistic Congress, and for the people who will be going. May it sow seeds, and may those seeds bear fruit, and may the Church be always renewed.

—

And before we get to the news, let me mention some intercessors who may be well equipped to pray for the Eucharistic Congress.

On July 9, 1572, 19 clerics and religious were hanged in Brielle — in Holland, the modern-day Netherlands — because they would not deny the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, or the supremacy of the pope.

They were 11 Franciscans, one Dominican, two Norbertines, an Augustinian, and four secular priests. Some were pastors, some cathedral canons, some chaplains to religious, some students. Two were lay Franciscan brothers.

By some accounts, some were good priests, and some were not. They were, in many ways, ordinary men.

But despite interrogations, torture, and bodily mutilation, none denied the faith.

After two weeks in prison, they died in a turf shed, holding the faith until the last. Their bodies were dumped in a ditch.

But local Catholics started visiting that ditch, mostly quietly, mostly at night. They called the men martyrs, from the start. And eventually, their relics were taken to a friary in Brussels.

They were beatified a century later, and canonized in 1860.

May those Gorkum martyrs, who held the faith, intercede for our national Eucharistic Congress.

The news

OK, we didn’t have a newsletter on Friday, so I’ve got a lot of news to tell you about. Here goes:

Schism is the “refusal of submission to the Roman Pontiff.” Viganó, for his part, denies that Pope Francis is the Roman Pontiff.

An excommunication is a medicinal penalty, intended to call Viganó to withdraw from his position, and thus return to the communion of the Church.

When Mincione’s attorneys accused Peña Parra of lying to them, he denied it.

But he admitted that when the Vatican was being blackmailed, he went along with the blackmail, signing off on a fake five million euro invoice and directing the Vatican’s bank to pay it, because he thought it would be the easiest way to get out of a bad financial situation.

In response to challenges to his integrity, Peña Parra was forthcoming: “You said that I was not honest. I accept that.”

This is a big deal — indicative of the scale of financial corruption, and managerial incompetence, which has been exposed at the Apostolic See.

In a well-sourced analysis, Ed considers why the Apostolic See is litigating that suit at all, instead of reaching a settlement with Milone.

In an interview with an Italian newspaper, Becciu said that his conviction “cries to heaven for vengeance” — and that while he had become a public “leper” during the trial, he had actually received private assurances of support from other cardinals.

“It hurt me to have been presented as a ‘business cardinal’,” said Becciu. “I'm not. Never has a penny gone into my pockets and the process has amply demonstrated this.”

“I have not dishonored the Vatican, I have given my life for the Church serving it throughout the world, in the various nunciatures, with dedication and commitment.”

Good ole Becciu.

Here’s the latest, read all about it.

People like Bianca Jagger, Andrew Lloyd Webber, Princess Michael of Kent, a member of Britain’s royal family — many of them non-Catholics, and some not believers — published a letter in the Times of London July 3, saying that the Latin Mass belongs to “universal culture,” because it had “inspired a host of priceless achievements in the arts — not only mystical works, but works by poets, philosophers, musicians, architects, painters and sculptors in all countries and epochs.”

The letter comes amid rumors — which The Pillar has not confirmed — that Pope Francis intends to issue new restrictions this month on the Extraordinary Form of the liturgy.

And the letter has precedent — in 1971, Agatha Christie, Graham Greene, and other cultural figures wrote a similar letter to Pope St. Paul VI.

The Institute of Catholic Culture is now enrolling students in Patristics 102: Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers! This free online course will explore the Fathers of the Church—some of the greatest minds in Church history—who helped articulate Catholic doctrine and were its staunch defenders against heresy. Learn more!

Episcopal appointments in the country are complicated by an agreement which gives Venezuela’s government the right to approve a new bishop before he is appointed. In recent years, according to local observers, the Maduro regime has weaponized that right to restrict the activity of the Church in Venezuela.

So what’s changed this year? Edgar Beltrán — himself a Venezuelan — has the best analysis you’ll read anywhere on that subject.

On that day, hundreds of priests faced the prospect of being declared in schism, if they refused to accept the controversial Eucharistic liturgy norms promulgated by the Eastern Catholic Church’s authoritative synod of bishops.

But July 3 came and went, and while the priests held out, they were not declared to be in schism.

In short, the situation for the Syro-Malabars, especially in the Indian Archeparchy of Ernakulam-Angamaly, remains completely unclear.

And with each passing “deadline,” Rome’s resolve to address the situation — at least according to its current strategy — seems increasingly wavering.

Here’s what’s happening in India.

The recent disclosures indicate that the nuns had racked up tens of thousands in unpaid charges on silk sheets, high-quality ham, and electronics — some of which they were apparently buying because, they told one vendor, an unnamed cardinal was coming to stay with them, and they wanted to spruce the place up a bit.

The nuns had a habit, though, of not paying their bills, neither for the sheets, nor for back wages owed to their employees.

But none of that is the strangest part of the story.

In addition to the other stuff, the nuns seem to have purchased a fighting bull, which they had to subsequently sell when they couldn’t tame it.

And that’s no bull.

Read about the convent here — and pray for these nuns. They need your prayers.

But observers say that things are getting worse for the Church in Nicaragua in recent months — and that we’re hearing less about it, perhaps, because Church leaders are too scared to speak up publicly, at all.

This is a nation where the apostolic nuncio, the Missionaries of Charity, 15% of priests, and a diocesan bishop have all been expelled. Universities have been seized by the government, and bishops are under constant surveillance by the government.

The situation is dire. And the bishops who remain may be trying to salvage what they can of the Church’s presence in Nicaragua — moving increasingly to a more “underground” style of existence.

Edgar Beltrán brings you a cogent and serious analysis of the situation on the ground.

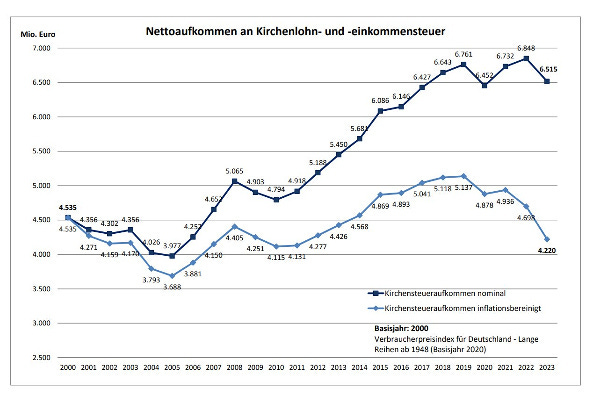

The reason is the Kirchensteuer — Germany’s “Church tax,” which sees the government collect revenues from Catholics, and distribute it to the Church, regardless of whether they darken the doors of the local parish.

But, as millions of Catholics disaffiliate, formally, from the Church, the Church tax is starting to see a crunch.

Indeed, the latest figures show that Catholic church tax income fell by around 330 million euros (roughly $357 million) in 2023, compared to 2022.

—

Finally in the news, something I’m quite excited about.

Each morning of the National Eucharistic Congress next week, a liturgy will be celebrated in Lucas Oil Stadium, at which tens of thousands of Catholics will be invited to come and worship together.

One of those liturgies will be something that most Catholics have never experienced before: Holy Qurbana, the liturgy of the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church.

The Qurbana is an ancient liturgical rite, which began in India, celebrated by Christians who say they were evangelized by St. Thomas the Apostle just decades after Christ rose from the dead.

I talked with Bishop Alappatt about the liturgy, the Syro-Malabar Church in the U.S., and the challenges facing Christians in India.

(And yes, liturgy friends, the liturgy will be celebrated according to the form approved by the Syro-Malabar synod of bishops!)

We had a fascinating conversation. Read it here.

Paydirt!

In July 1858, almost a decade after the California Gold Rush, a prospector named William Greeneberry "Green" Russell found a nugget of gold near the mouth of Little Dry Creek, in the western part of the Kansas territory.

The next day he found another, then another. He’d hit paydirt, and soon found 20 ounces of gold in the river, worth about $44,000 in today’s money. When he told people, Russell set off one of America’s great gold rushes.

More than 100,000 people flooded the area, with gold pans and sluice boxes and dreams of getting rich. Some did. But most worked pretty hard, traipsing through the Rocky Mountains’ foothills, without all that much to show for it.

Green Russell found his gold in what was then open country, the scrub prairie leading up to the Front Range of the Colorado Rockies.

Today, there’s an auto body garage, a coin dealer, and a pawn shop standing along the spot where Green Russell set off the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush. The creek is overgrown, bordered by concrete, and strewn with shopping carts and beer bottles. If there’s gold under the water there, you’d want to wear thick gloves while looking for it, and wash your hands thoroughly when you’re done.

But the Pikes Peak Gold Rush gave America the cities of Denver, Boulder, and a whole host of smaller Front Range towns, all of which started out as mining camps. Some of the biggest finds in the area came from the confluence of Cherry Creek and the South Platte River, at the spot where, today, you can find a very large downtown Denver REI — which, come to think of it, would have been helpful to the underprepared prospectors of yesteryear, who came out to Colorado without Hydro Flasks or technical sleeping bags.

I know about all of this because my recently-seven-year-old son, Daniel, has become pretty interested in Colorado’s gold mining history, or at least interested in the gold itself. For his June birthday, he received the gold panning set he’d been begging for, which means that we were expected to actually take him panning, or else be pretty lame about the gift we’d gotten him.

So we scouted some spots. It is not easy to find a spot for panning in Colorado, because most of the state’s rivers, streams, and creeks have mineral claims attached to them, and if you pan for gold where someone has got a claim, you could get arrested.

Imagine being booked at a county jail, and explaining to your fellow inmates that you got pinched for illegal gold prospecting. They’d probably steal your lunch pretty quick.

You can pan for gold in state parks in Colorado, and there’s plenty of them to choose from. But you’re not supposed to keep the nuggets you find in Colorado’s state parks, at least not unless you get permission from a park ranger. I imagined we’d strike it rich pretty quick, and I didn’t want to have to deal with some Ranger Rick trying to squeeze in on my action, so I took those parks off our list.

There are a few other spots where one can pan.

A good prospector never tells. But I will say that on the morning of July 5, we parked our car in an industrial neighborhood north of Denver, between an RV storage lot and a carpet cleaner’s warehouse, and we hiked for a bit to our prospecting spot, somewhere along Clear Creek.

We scrambled down to the actual river, and, based upon the five or six YouTubes we’d watched, we got to work.

Or some of us did.

Max, for his part, pretty quickly stretched out on a blanket, in the late morning sun, and started to nap. Pia took a gold panning shovel, sat down creekside, and started digging a deep hole. Davey prospected for a minute or two, putting rocks and sand in his pan like we’d seen on YouTube. Then declared it boring, asked me to let him know when we’d struck it rich, and starting playing with his prospecting magnet.

We also had my mother-in-law in tow. She was a good sport, but I think that when we told her we’d be going gold panning, she imagined we’d go to a tourist spot in a mountain town, where a guy in a Prospector Pete costume would say a few things with an old-timey accent, and then the kids would plunge their hands into a cold water bucket and pull out some chocolate gold coins.

She didn’t know we’d go panning for real.

Still, my mother-in-law sat along the riverbank and dutifully filtered rock with a screen, probably still wondering, after almost two decades, about this oddball her daughter had wed.

Kate and I tried to get serious about the work. Kate set up our small sluice box, shoveling dark riverbank sand into it, so that rough ridges along its bottom could trap any flakes of gold.

I tried my hand at traditional panning. I filled up my pan, I very slowly agitated the contents so the gold sank to the bottom, I held it in the water so the lighter stuff could sift away. But before I could call Davey over to run his powerful magnet over my dark residue at the bottom, in which gold might be found, Pia dumped a few more scoops of sand into my pan, along with a few large, light-colored rocks which she swore were “pirate gold.”

So I started again.

I learned that gold panning is slow work, under the hot sun, and for the prospect of probably clearing something like six dollars an hour, if a few flakes can be found. Still, I did find it relaxing to have my legs in the cold rushing creek, and to listen to my children play adventure games along the riverbank. And I liked prospecting alongside Kate — I imagined that if some global catastrophe were to come, we’d be a good team finding valuable gold, and at least one day’s panning experience ahead of other families.

The early birds catch the gold, and all that.

On Friday, there were just a few other prospectors along the river bank at our spot.

Eventually — I kid you not — a kindly older prospector approached me, and asked me to show him my technique. It was a very gentle way of observing that I had no discernable technique.

He showed me a few things, and I tried to learn, but his panning technique was far superior to mine. He ended each panful with a very small amount of magnetite — black magnetic sand — and a few small flakes of gold, which he put with tweezers into a little glass vial he’d brought.

I ended each panful with a slurry of sands, a few sparkly bits, and no chance at reclaiming my tweezers, which my kids had requisitioned for the purpose of tormenting frogs, I think.

Still, after the prospector packed it in, and while Kate and her mom caught up on the riverbank, I kept it at. And eventually, I maybe got the hang of panning for gold. The hardest part is trust: You’ve got to tip your pan into the river, to let the dark sand flow out, while trusting that the gold is heavy enough to stay in the bottom, and stick in your pan.

Either you don’t trust, and you can’t separate the gold from the junk, or you’re too cavalier, and you pour everything out all at once.

There was probably a good spiritual metaphor in there somewhere. But by the time I might have considered it, my older kids were already talking about getting hamburgers, and Davey was batting large rocks in my direction, with a broken branch he’d found in the river.

It was time to go.

Still, there’s gold in the rushing waters of the Front Range. I’ve seen its glint in my very own pan. I might go back again to sluice it out.

I’m sorry I can’t tell you where to look. It’s the law of the West, and all that.

—

Please be assured of our prayers. And please pray for us. We need it.

If you want to support our work at the Eucharistic Congress next week, now is a darn good time to subscribe:

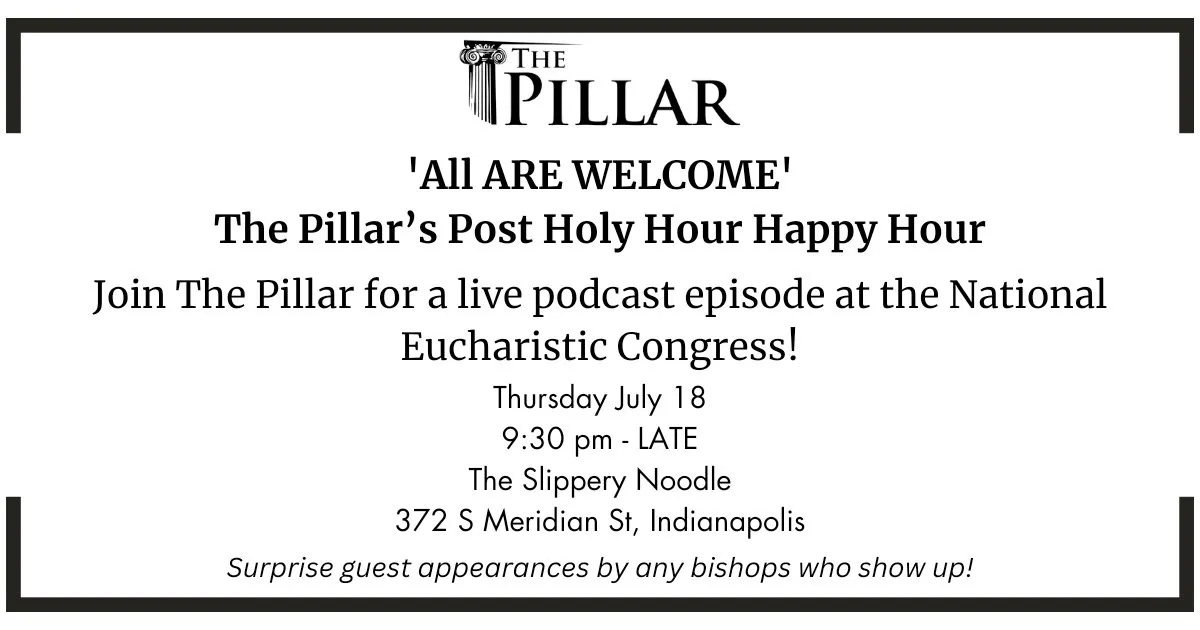

And don’t forget, if you’ll be in Indiana, to come to our live show at the Slippery Noodle, July 18. We can talk gold panning for a while.

Yours in Christ,

JD Flynn

editor-in-chief

The Pillar