‘Pacem in terris’ at 60: A brief guide to a landmark encyclical

Why is 'Pacem in terris' remembered when other, more recent encyclicals have been nearly forgotten?

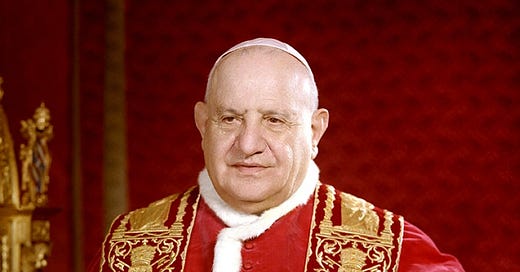

Sixty years ago this week, Pope John XXIII published what would prove to be his final encyclical.

The Italian pope would die less than two months after Pacem in terris was released April 11, 1963.

The encyclical’s 60th anniversary year is being marked with conferences, essays, and papal messages.

But why is it still remembered when other, more recent encyclicals have been all but forgotten? The Pillar takes a look.

The shadow of nuclear war

Pacem in terris appeared at one of the most dangerous points in the Cold War, the post-Second World War standoff between the United States and the Soviet Union, and their respective allies.

The encyclical was issued months after the Cuban Missile Crisis, sparked by the Soviet construction of nuclear missile sites on the island within striking range of the U.S. On Oct. 22, 1962, John F. Kennedy — America’s first Catholic president — announced a naval blockade of Cuba in response.

In an address to the nation, Kennedy said: “It shall be the policy of this nation to regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union.”

On Oct. 25, John XXIII, who had opened the Second Vatican Council two weeks earlier, addressed the crisis in a radio broadcast.

“We beg all governments not to remain deaf to this cry of humanity,” he said in French, the premiere language of diplomacy. “That they do all that is in their power to save peace. They will thus spare the world from the horrors of a war whose terrifying consequences no one can predict.”

“That they continue discussions, as this loyal and open behavior has great value as a witness of everyone’s conscience and before history. Promoting, favoring, accepting conversations, at all levels and in any time, is a rule of wisdom and prudence which attracts the blessings of heaven and earth.”

The pope’s intervention was reported prominently by Pravda, the Soviet Communist Party’s official newspaper. Shortly afterward, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev agreed to dismantle the Cuban missile sites (in return for then secret concessions from President Kennedy).

The crisis was the closest the world had come to all-out nuclear war. While disaster was averted, the Cold War would continue for almost 30 years and arguably still hangs over world affairs today.

—

—

The twilight of a pontificate

Cardinal Angelo Roncalli, the third of 13 children born to a family of sharecroppers in northern Italy, was elected pope in 1958. He was selected unexpectedly after 11 ballots, taking the name John XXIII.

Aged 76, he was dismissed as a “caretaker pope” who would keep the Church running while the cardinals identified a younger, more vigorous leader.

On Sept. 23, 1962, John XXIII was diagnosed with stomach cancer. On Oct. 11 that year, he opened Vatican II, an ecumenical council that he hoped would renew the Church as it grappled with the grave challenges of the 20th century.

He wrote a total of eight encyclicals, two of which are still regularly cited: 1961’s Mater et magistra, on “Christianity and social progress,” and Pacem in Terris, on “establishing universal peace in truth, justice, charity, and liberty.”

The title of his last encyclical came, following the papal custom, from its incipit, or opening words: “Peace on Earth.”

“Peace on Earth—which man throughout the ages has so longed for and sought after—can never be established, never guaranteed, except by the diligent observance of the divinely established order,” John XXIII declared.

The encyclical was addressed not only to Catholics but also, for the first time, to “all men of good will,” a practice that would be taken up by John’s successors.

The Italian pope chose to sign the encyclical on April 11, which in 1963 was Holy Thursday.

By doing so, he linked the encyclical “to the Holy Week celebration of the passion, death, and resurrection of Christ — the event and mystery upon which the faith and hope of the Church rests,” as former Vatican official Peter Coughlin recently noted.

‘The impending storm’

Over almost 15,000 words, John XXIII set out what he believed to be the conditions of a lasting global peace, against the background of what he called the “signs of the times.”

The encyclical had four main sections: “order between men,” “relations between individuals and the public authorities,” “relations between states,” and “the relationship of men and of political communities with the world community.”

Some passages read as if they could have been written today, given the nuclear threats accompanying Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

John XXIII noted at one point that his contemporaries were “living in the grip of constant fear.”

“They are afraid that at any moment the impending storm may break upon them with horrific violence. And they have good reasons for their fear, for there is certainly no lack of such weapons,” he wrote.

“While it is difficult to believe that anyone would dare to assume responsibility for initiating the appalling slaughter and destruction that war would bring in its wake, there is no denying that the conflagration could be started by some chance and unforeseen circumstance.”

“Moreover, even though the monstrous power of modern weapons does indeed act as a deterrent, there is reason to fear that the very testing of nuclear devices for war purposes can, if continued, lead to serious danger for various forms of life on earth.”

The encyclical called for a ban on nuclear weapons, expressing hope for “a suitable disarmament program, with an effective system of mutual control.”

But John XXIII went further, imagining a world in which all arms were eliminated.

“Everyone, however, must realize that, unless this process of disarmament be thoroughgoing and complete, and reach men’s very souls, it is impossible to stop the arms race, or to reduce armaments, or—and this is the main thing—ultimately to abolish them entirely,” he wrote.

“Everyone must sincerely cooperate in the effort to banish fear and the anxious expectation of war from men’s minds. But this requires that the fundamental principles upon which peace is based in today's world be replaced by an altogether different one, namely, the realization that true and lasting peace among nations cannot consist in the possession of an equal supply of armaments but only in mutual trust.”

—

—

‘Voice of the conscience of the world’

Pacem in terris received arguably the best reception of any 20th-century encyclical.

It was published in full by the New York Times, while the Washington Post said that the encyclical “is not just the voice of an old priest, nor just that of an ancient Church; it is the voice of the conscience of the world.”

Pacem in terris was cited approvingly by both U.S. Vice President Hubert Humphrey and Pravda’s deputy editor-in-chief Nikolay Inozemtsev, and it was placed in the United Nations archives in New York in recognition of its historic significance. It was even set to music by the French composer Darius Milhaud.

The encyclical continues to inspire Catholics striving for peace in the 21st century.

In a 2006 Angelus address, Benedict described it as an “immortal encyclical,” while Pope Francis said in 2013 that it continued to be “extremely timely” and cited it in a 2023 Easter message.

In his 2013 speech, Francis highlighted John XXIII’s radicalism, his vision of peace not simply as the cessation of warfare but as a far-reaching transformation of human affairs.

“Pacem in terris draws a line that goes from the peace to be built in the hearts of men to reviewing our model of development and of action at all levels so that our world may become a world of peace,” Francis observed. “I ask myself, are we willing to accept this invitation?”

John XXIII’s appeal is no less challenging today than it was 60 years ago.

Our Lady of Fatima said if we want peace we need to pray the rosary daily and make the 5 first Saturdays.