Happy Good Friday friends,

I say happy, and that feels odd. Happiness is not really the word you reach for when contemplating our own cross. But, at the same time, when considering the Passion each year, I cannot but hear in my head the words of the paschal Praeconium: “Oh happy fault, that deserved so great a savior.”

It is, for me, one of the purest consolations of the Triduum that, whatever personal sins are weighing on me, and whatever it is in the world that tempts me to despair, the awful majesty of the crucifixion and the seismic, cosmic rupture of the power of death rendered by the reality of the resurrection dwarfs all else by comparison.

So great a savior indeed.

JD and I have been trying to focus ourselves on the spiritual this Holy Week, and we made the conscious decision to step back from our usual pace of coverage on earthly affairs. We take our work at The Pillar seriously as a journalistic endeavor, and try to treat it with all the professionalism it deserves.

But no less do we consider it a work of service, to the truth and to the Church. It is important for us that what we do, how we report the news, remains rooted in and a fruit of our own spiritual life in the Church — the often messy reality of the Church in the world finds its proper place only within its larger reality as the sacrament of salvation for the world.

Quick Links

To this end, we talked to a few people about celebrating the Triduum in out-of-the-ordinary circumstances as a help for us to focus on Easter. Hopefully it helps for you, too.

—

—

We should remember that the victory of Christ over death and darkness is lived not just as a metaphor for so many persecuted Christians, many of them closer to home than you might think.

Truth and Life

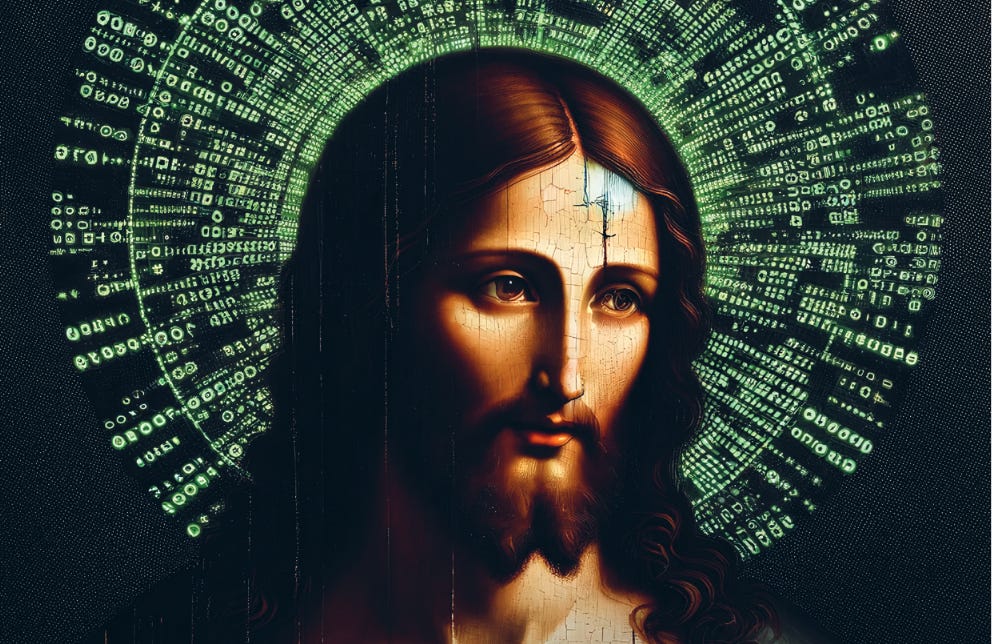

The power and mystery of the Easter mysteries is the sheer visibility of them for those present. The man called Jesus, the one the Apostles looked to to usher in the kingdom of God, the Messiah, was graphically and indisputably put to death on Good Friday, and in the most violent and degrading manner devised by man.

The scandal of the cross gave way to the shock of the empty tomb, and the magnificent terror of the appearance of the risen Lord, but even then some of those who knew him best were slow to believe their eyes.

Truth, even obvious, apparent truth, is still today the focus of so much of our social discord. The administration of “devout Catholic” Joe Biden remains absolutely committed to forcing through the Equality Act, which would make liars and criminals of those who would announce even the most obvious truths of human biology, calling men men and women women.

Our grasp on objective truth is a little bit like our sense of balance — we tend to take it for granted until we lose it, and having lost it we find ourselves reeling. And the moral relativism against which the Church has long warned has now given in to factual and scientific relativism.

When I lived in London, and before the ubiquity of smartphones to settle every question, a member of my drinking circle would often introduce obviously wrong statements with the phrase “The fact is…,” to the annoyance of everyone.

Fifteen years ago, such rhetoric was reserved to pub bores and adolescents learning to argue. Now, it is accepted journalistic practice.

Earlier this week, CNN ran a “news” report which included this rather striking statement of supposed facts: “It's not possible to know a person's gender identity at birth, and there is no consensus criteria for assigning sex at birth.”

I know nothing about the “reporter” who reported these “facts.” It may be that they have no more experience of babies being born, or of basic human anatomy, than they do proper writing style — who uses contractions in formal prose, I ask you? But the fact is, to borrow a phrase, such counter factual statements are increasingly the required norm of public discourse.

Everything is becoming relative, and the inherent contradictions are everywhere to see.

In New Zealand last week, a new law was passed giving statutory bereavement leave for pregnant mothers who lose their child through a miscarriage, even in the earliest stages of pregnancy.

This is an obviously humane and praiseworthy measure. It is also, one would think, an obvious recognition that in any miscarriage a mother loses a child, with all the grief that comes with that tragedy. Yet the Washington Post, in its tacit praise for the measure, bracketed it with New Zealand’s recent total decriminalization of abortion, holding both policies out as victories for women’s rights.

The juxtaposition of the two measures by the same government is a striking example of the paradoxes created when you enshrine the concept of relative truth in law: A miscarriage is a tragedy, a true loss for the mother, and life which needs to be mourned; an abortion is the exorcising of a clump of cells, without worth, humanity, or dignity.

Unborn life is now, in New Zealand, simultaneously real and unreal, with the question only settled when we know how the pregnancy ends, a sort of “Schrödinger’s Baby,” if you will.

Such offenses against life, truth, and basic human reason can tempt us to fury, to vent our opposition in swivel-eyed and spittle-flecked rage. It is not an unreasonable or unjustified urge, humanly speaking. But the Easter Triduum, and especially Good Friday, reminds us that this is not the Christian answer.

The Suffering Servant on the cross went there as the meek and willing witness to the sins of our world, and he did so not to condemn it, but to redeem it. The night before he died, Christ told his disciples “I am the Way; I am Truth and Life.”

We who want to be his disciples must follow in his path, announcing the truth with the love which mounts the cross. Modeling this love is, by no means, an easy witness to offer, but we should draw courage from the knowledge that this truth speaks to our broken world: As Christ breathed his last, it was the pagan centurion who stared at the corpse of a condemned criminal and marveled “Truly, this man was son of God.”

See you next week, and Maranatha!

Ed. Condon

Editor