Monk alleges abuse - and retaliation - at Silverstream Priory

A Pillar longread

Almost nothing about Fr. Benedict Andersen’s experience of the Catholic Church has been typical.

He was baptized a Catholic, but raised in evangelical communities, and spent most of his twenties in the Orthodox Church. He became a priest in 2014, but was never formally a Catholic seminarian, and was not yet a solemnly professed member of his monastery when he was ordained.

And all of his experience as an adult Catholic coincides with his time at Silverstream Priory, a well-known Benedictine monastery, of which Andersen was a founding member.

Unusually, he took the habit at the same time he returned to the full communion of the Catholic Church — he “went to confession, made a profession of faith, and a couple minutes later I was clothed in the habit,” he recalls.

Some of that is unusual enough to raise the eyebrows of canon lawyers. “As I’m learning, a lot of things were not done in the right way...at Silverstream Priory,” Andersen told The Pillar.

Andersen now claims he is in another unusual situation: he is out of ministry and without priestly faculties, living thousands of miles from his monastery, and accused of a canonical crime he insists he didn’t commit.

The priest alleges that since he spoke out about years of troubling behavior within his monastic community, he has been ostracized, accused of violating the confessional seal, and been left without a ministry, a home, or a way forward.

That’s another unusual thing about Andersen: While his monastery, Silverstream Priory, is frequently praised by Catholics as an example of thriving Benedictine religious life, the priest says it was for him also a place of harassment and manipulation, which he reported to his bishop in April 2020, and to official visitors soon after that.

And while Andersen says he has mixed feelings about the monastery he long believed was his vocation — and is still trying to figure out if that’s true — he claims he’s been exiled, with no idea of what will come next.

Andersen says he’s come forward to tell his story because he’s out of options: He wants to preserve his priesthood, and he isn’t sure where to turn next.

The priest also said he knows his monastery is beloved and admired by Catholics around the world, who feel some connection to it through “In Sinu Jesu,” the spiritual diary of the community’s founder, Fr. Mark Kirby.

He spent weeks deciding whether to conduct an interview on the record, apparently wary of the possibility of scandal, and seemingly reticent to tell his story. But he told The Pillar he believes the best way that he can serve the Church is to tell the truth, and he said he believes the truth has not been told.

There is a clear disparity between an official investigation’s account of the priory, and Andersen’s view. The priest says that’s because the 2020 apostolic visitation to Silverstream didn’t address, or even investigate, his most serious concerns.

But is Fr. Benedict Andersen a whistleblower facing persecution? Or is there more to the story?

If officials of the monastery, the apostolic visitation, and the priest’s Irish diocese have a different perspective on what’s happened, they’re not saying.

The officials who have responded to questions from The Pillar say they can’t speak about pending canonical matters, including the circumstances of Fr. Benedict Andersen and Silverstream Priory. But at least one public account of the visitation is incomplete, and Andersen says inaction from ecclesiastical officials has left him in a kind of limbo.

‘I don’t think this is for me’

Silverstream Priory is a quiet monastic community in Ireland’s rural, agricultural County Meath, just 20 miles north of Dublin. The monastery gained international attention in 2016, after the publication of “In Sinu Jesu.”

Silverstream itself was founded in Ireland in 2012, but its community began a few years earlier, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where Fr. Mark Kirby went to live as a priest after leaving a Cistercian monastery in Canada.

Kirby wanted to form a Benedictine community of monks who would celebrate the Extraordinary Form of the Mass and commit to perpetual adoration of the Eucharist.

Andersen moved to Tulsa in 2010 to join Kirby, after he read about the priest’s vision for a monastic community on his now-offline blog. Andersen was returning to the practice of the Catholic faith after a decade in Orthodoxy, which included formation for priesthood. Andersen was then 31, Kirby was 60.

Kirby became a mentor and a spiritual father to Andersen, who was eager to learn about Catholicism, and had little practical experience of the Church except for his life with Kirby. He admired the priest’s faith, and wanted his vision for a monastery to work. Andersen wasn’t yet a novice; he was an aspirant in the community — a person at the entry level of discernment and commitment.

Other men came to discern a vocation with Kirby, some became novice members, but few stayed for very long. After one novice member left the community in 2011, the house was down to Kirby and Andersen.

Andersen said that novice left after strange experiences with Kirby, and that the priest seemed to act possessive toward him. It bothered him. And Andersen decided he would leave too.

But things didn’t work out the way he planned.

As Andersen prepared to leave, Kirby got sick — a chronic auto-immune condition flared up.

“The novice is gone, Kirby is extremely, extremely sick, and kind of distraught. I can leave at any time, but I thought, ‘It’s not right. This guy’s pretty sick.’ So I stayed around for probably a week or two weeks just kind of looking after him, and at the end of that, I sat him down and said, ‘I don’t think this is for me.’”

And then, Andersen alleged, “something very weird happened.”

The priest said that Kirby began to recount to him his own experiences of being serially abused, in graphic and explicit detail. He said Kirby talked for nearly an hour. Andersen was disturbed by what Kirby told him, and by the way he told it — behavior he describes as grooming, and says he now realizes was manipulative, seemingly designed to keep from leaving.

“And so I’m sitting there, and on the one hand I am freaked out. And one the other hand, this man is pouring his life out to me. And he’s very distraught and he’s crying. And I really don’t know what to do.”

“But it was highly manipulative, because in a sick, weird way that kind of bound me to him. While I did leave that day, I don’t know why, but I decided to come back and help him.”

Andersen left for a month or two, he said, and then he came back.

“He really was extremely flattering. He just kept saying ‘I know you could do well here, and you could really make this place go, and I need you, and you’re so talented.’ And looking back, it was kind of...in retrospect. I was locked in this weird emotional thing with him,” Andersen told The Pillar.

He alleged that Kirby used his self-disclosure, and his knowledge of Andersen’s own background, to manipulate him into a relationship he described as “codependent.”

“I should have run out of that place and just left,” Andersen reflected.

Spiritual abuse

Archbishop Jose Rodriguez Carballo, secretary of the Vatican’s office for religious orders and institutes, said last month that his dicastery is investigating about a dozen founders of newly established religious institutes, who are suspected of spiritual abuse: of manipulation, psychological, physical, and sexual violence, of abusing power, and for “problems related to affectivity” — the Vatican’s euphemism for crossing personal boundaries.

Spiritual abuse “is usually more common than you might think. Pope Francis defines it as spiritual harassment, manipulation of consciences, brainwashing,” he said.

“This type of abuse usually occurs in the sphere of spiritual direction or within a community, especially when the internal forum (the individual’s conscience and spiritual state) is not distinguished from the external one,” Carballo added.

Carballo said that discerning when a new community is inspired by the Holy Spirit isn’t easy, but it is important.

Spiritual abuse in religious communities “does a lot of damage to consecrated life and to the church itself,” he said.

“Therefore, much more attention should be paid when discerning the need, benefit and usefulness for the church when approving associations whose canonical recognition is underway.”

Andersen told The Pillar that kind of attention is critical in a new community. And he said his experience at Silverstream Priory — a place he loves, and a place he knows is beloved by Catholics around the world — is a lesson about what can happen when a charismatic founder is imbued with spiritual authority but with little supervision or oversight. The damage, he said, can be life-altering.

At least, he claimed, it’s altered his life.

Silverstream

Andersen and Kirby left Tulsa in February 2012. They had been permitted to form a monastic community in an empty convent in the Diocese of Meath, Ireland. They would call the monastery Silverstream Priory.

Andersen said the move happened very quickly, under stressful circumstances, amid escalating tension between Kirby and officials in the Tulsa diocese over money, the priest’s role in the diocese, and Kirby’s long-standing desire to find a place for a permanent monastery.

The move also seemed to happen without much research; several sources close to the monastery told The Pillar that the Tulsa diocese was not consulted before the group was permitted to set up a house in Ireland.

Andersen said that Kirby was personally charismatic and dynamic, inspiring trust and painting an attractive vision for monastic life. That, he said, is why the men were able to move to Meath without much of a look into their backgrounds.

But he said in Ireland they moved into a building in disrepair, with mold that made them sick. It took years to renovate it well.

More troubling, he said, is that Kirby continued to treat him in ways that felt like grooming: inappropriate personal disclosures, a lack of physical modesty, unwanted hugs, a way of holding the younger man’s arm as they walked through the garden. He was especially concerned by Kirby’s habit of frequently telling him sexually inappropriate memories and experiences, usually in detail.

Andersen says he tried to get Kirby to stop, but the priest waved him off.

“And again, I wonder why I'm not like running out of this place, you know? But I'm sitting here going, ‘Okay, well, he's obviously traumatized by this. He's wanting to talk about it with me….This really isn't appropriate, but all right.’”

Andersen said that over the years, Kirby seemed increasingly infatuated with him. He told the younger man that he had filled dozens of prayer journals with prayers and reflections about him. He hugged him too closely, Andersen said, and developed the habit of “caressing my head.”

Kirby called him “my Benedict.” He visited his cell at all hours of the day, Andersen said, without knocking and without permission.

“I only found out later that it’s not appropriate for a prior to enter the cell of a novice several times a day. But that’s the kind of thing he was doing.”

Silverstream Priory did not respond to requests from The Pillar for an interview with Kirby and other monks.

The Pillar reached out to senior clerics close to the monastery. None was willing to speak on the record, citing Kirby’s popularity and the ongoing apostolic visitation. But one cleric told The Pillar that Andersen’s allegations seemed truthful, and that Kirby seemed “in love” with Andersen — “not sexually, but emotionally.”

Andersen described that “love” as “spiritual and emotional abuse, along with persistent sexual harassment.”

Still, he said, he found he couldn’t leave.

Andersen wanted to be a Benedictine, and a priest — and he was ordained in 2014. He felt he had made a commitment to the community. He loved the stated charism and identity of the priory, at which monks offer the Extraordinary Form of the Mass and spend hours in contemplation before the Blessed Sacrament. And he believed it was his vocation — God’s will — that he be there.

Those things are not always understood in the world, Andersen said. But for a Catholic, the sense that the monastery was his vocation made it very difficult even to acknowledge to himself the magnitude of its problems. And he’s still sorting out, he said, where the Lord really was in all of this, and what’s he called to do next. It can be confusing, he conceded.

Why did he stay?

“There were many things about Silversteam Priory that were wonderful. The liturgies were wonderful. The monks were good men. I became a priest, I was the sub-prior, and I was able to do work that I really enjoyed,” Andersen said. He said he frequently downplayed and made excuses for Kirby’s behavior — that the man was gifted in many ways, that there were certain lines he hadn’t crossed.

Also, Andersen said, he felt manipulated in ways that impinged his freedom. He claims that when he would tell Kirby he was thinking about leaving, the priest would say that no other monastery would take him, and that he had no marketable skills.

Once, the priest broke down weeping when Andersen said he was leaving, crying that he depended upon the younger priest for everything.

Andersen claims Kirby also insisted he was depressed and anxious, and frequently urged him to take psychiatric medication — a charge he initially disagreed with, but gradually came to believe, as his superior insisted with frequency. And he said that as his relationship with Andersen grew dysfunctional, he did find himself both anxious and depressed.

“The problem was not chemical. The problem was situational. Being in the presence of this guy. And I couldn’t figure out what was wrong.”

He said Kirby told other people, including monks at the monastery, that Andersen was depressed — a way, Andersen felt, of controlling him.

Andersen recalled that one time when he told Kirby he was leaving, the priest used that tactic. “He said, ‘You’re depressed and anxious and no one’s going to take you now. You need to stay here with me.’”

Andersen wasn’t sure whether he believed that. But he stayed.

After they were established in Ireland, the monastery grew.

American and Irish aspirants entered Silverstream, along with an Australian and a Dane. With eight monks, Silverstream was granted canonical status as an institute of consecrated life of diocesan right, in February 2017. There were 15 monks by early 2020.

But as Silverstream gained vocations, Andersen said things got increasingly strange. Organization seemed haphazard, as did the formation of young monks. Andersen himself did not study formally at a Catholic seminary while a member of the monastery — his Orthodox formation and “a few weekends with a priest” were judged to be enough.

Monks were not usually allowed to go to the doctor — even into the exam room — without another member of the community with them. Andersen says that when he complained about some practices, Kirby directed him to visit a therapist, and required a community member to attend his initial appointment.

Andersen, who became the monastery’s sub-prior, said that Silverstream did not develop formal practices of good management, accounting, or accountability. He noted that the monastery did not observe many of the norms regarding decision-making, division of labor, and protection of the internal forum delineated in its own statutes and the Benedictine rule.

On finances, Andersen recalled a desk drawer with “thousands of euros” in it, and lamented the monastery’s failure to keep records or plan its budget. He said it had a habit of waiting for emergencies and then fundraising— but that because Kirby is a talented fundraiser, things usually worked out.

Andersen also alleged an incident in which Kirby gave a volunteer 6,000 euros in cash, after the volunteer accused Kirby of some unspecified but inappropriate sexual conduct. That incident, which happened in the early years of Silverstream’s presence in Ireland, he eventually recounted to the police. But it took years before he could do so.

‘I had to write to the bishop’

Over the years, Andersen continued to raise his concerns to Kirby, but tensions in the monastery only heightened. Eventually, Andersen said he asked permission to take a break from Silverstream. In autumn 2019, he went to for graduate studies at the Orthodox seminary in New York state where he had studied before he joined Kirby.

But after a semester, Andersen said, he went back to Silverstream, because he was told by other monks that Kirby was ill, and he was uncertain how the monastery would function with no one at the helm.

But when Andersen told Kirby he was coming home to Silverstream, his superior insisted that Andersen return to Ireland on a ship, rather than an airplane.

“This is one of the weirdest things with Father Kirby I've ever experienced,” he recalled. He said he couldn’t understand why Kirby was adamant that Andersen cross the Atlantic on a ship. It just didn’t make sense.

But after pushing back, he accepted the unusual instruction as a matter of religious obedience.

“It cost $4,000. I mean, that’s insane.”

His ship set sail in January 2020, and took a week to reach its port in Southhampton. Halfway across the ocean, Andersen was informed by the ships’ officers that the monastery had called to make a check on his health. He found that strange, especially after Kirby explained it.

“When I returned, Father Kirby tells me: ‘I was very concerned about you. I was celebrating Mass and during the canon, a voice in French told me that Father Benedict has passed from this world. He is at peace.’ He interpreted that as a voice from heaven telling him that I had committed suicide by jumping from the side of the boat.”

“And this is where I think he is literally mentally ill. I still can’t figure out the whole boat thing. It’s very, very, very bizarre,” Andersen said.

But things got worse. And he found he couldn’t make excuses for Kirby’s behavior any longer.

The next three months “were absolute hell,” Andersen alleged.

Things came to a head on April 25, 2020. Kirby was sick in bed, and Andersen went to speak with him in his cell. He was there to tell him that things needed to change.

“I said, ‘I have to get out of here unless you can do something about this weird emotional thing. I feel like I’m in a weird emotional prison.’”

“I told him that ‘you’re the spiritual father of this monastic family, and we’re headed for a big disaster unless you renounce this.’ I said that I came to the monastery to be a monk, and you have never let me be a monk,” he recalled.

“I framed it in terms of spiritual warfare. I said ‘There’s something spiritual here that you have to renounce as the father of this monastery.’”

According to Andersen, Kirby’s reaction was unsettling.

He said the priest “jumped out of bed...and started reciting prayers really fast. The St. Michael prayer, really fast, and in a very weird way. And so I told him that things were a bit weird for me and I left his room. But he started texting me, saying ‘Where are you? Where are you?’ over and over. Like 15 or 20 times.’”

The Pillar reviewed the text messages described by Andersen.

“At one point he just texts the word ‘hospital.’ I don’t even know what that means. Then the word ‘Jesus.’ And I don’t know if he’s cursing, or if he’s calling on the name of Jesus, or what.”

“That night I was so afraid. I thought this guy is absolutely out of his mind. I mean everyone else is in bed at this point, and this guy is in his pajamas, going all over the monastery looking for me.”

“I really didn’t know where to go, but there was a graveyard on the property, so I just walked to the graveyard and hid behind this hedge while he texted me over and over. So the next day I went to a hotel in Dublin.”

“And basically I was convinced that I had to write to the bishop.”

Bishop Tom Deenihan, the Bishop of Meath, was not the bishop who had invited Silverstream to Ireland, or ordained most of its priests. He had effectively inherited the monastery when he became Meath’s bishop in September 2018, and was mostly hands-off with the community, despite its problems.

Andersen said he had spoken to Deenihan a few months before, in February 2020, about some of his concerns in the monastery. He even said he was thinking about leaving. He said Deenihan had made him feel like the problems were his to solve.

On April 30, after the incident with Kirby, Andersen wrote him a lengthy letter.

The letter explained Andersen’s sense that Kirby had manipulated him and violated boundaries for nearly a decade. The priest wrote that he believed those things had completely disrupted the life of the monastery, and that he believed himself to have incurred post-traumatic stress disorder from the experience of years of instability.

Andersen said he also explained to the bishop the monastery’s financial mismanagement, and concluded that he did not believe that Kirby could effectively remain the community’s superior.

Deenihan ordered a diocesan visitation — an inspection and assessment — of the monastery.

He appointed two Irish Benedictine abbots and another priest to conduct the visitation. Before the visitation started, Andersen left the monastery, going to live temporarily in Dublin. He wrote lengthy letters to the visitators, accusing his superior of spiritually and emotionally abusing him, and detailing financial and operational mismanagement at the priory.

Andersen said he hoped Kirby would be removed or resign, and that the Silverstream Benedictines would be encouraged or directed to join a federation of Benedictine monasteries, for the sake of some stability as they grew, and to provide temporary leadership for the young, small, and — in his view — dysfunctional Silverstream Priory.

He also hoped that the visitors would take seriously his allegations about Kirby. He put them in touch with others who had experienced similar behavior, who reportedly told the visitors they had also witnessed inappropriate personal disclosure, grooming, and other misconduct on Kirby’s part.

‘A huge mistake’

Before the visitation got underway, Andersen did something he now calls a “huge mistake.”

He says it set the tone for everything that has happened since. And he told The Pillar he wishes he could take it back.

A few days after the night he hid from Kirby, he went back to the monastery, and stayed at the guesthouse.

He says he tried to talk to Kirby about what had happened, but they got into an argument — and that because the monks were observing COVID-19 restrictions, the argument was in public.

A few monks who weren’t aware of what was happening stepped into the middle. Things escalated, and Andersen was angry.

One of the monks said that Andersen was being antagonistic toward Kirby, and even acting unstable. Andersen was furious, but he tried to leave.

When the priest tried to walk away, he said, the other monks “kind of surrounded me,” as they tried to understand what was happening. He said the monks wouldn’t let him leave, and he called 999, the Irish equivalent of 911.

“It was only then that they actually dispersed,” he said, and Andersen left, after calling the police back and telling them not to come.

He says the whole thing was a mistake.

“It was a stupid, stupid thing for me to do, because it allowed them to say that I was the one acting crazy,” Andersen said, especially because the other monks had no idea what had transpired between him and Kirby, or even that the bishop was planning a visitation.

“I kind of felt like I had made a gigantic mistake in doing all of this. I’m not sure what else I could have done, because I felt threatened. But the event really allowed the bishop to say, ‘Well, you really shouldn’t be resident in Silverstream for the duration of the visitation. You have to leave.’ The problem is the visitation is still technically on. So I don’t have the right to return.”

‘Matters are still ongoing’

The visitation was announced to the monks in May 2020, but the coronavirus pandemic slowed down the process. It was June 9 when the visitors went to the monastery, where they spent three days interviewing the monks.

Andersen, living in a short-term Dublin apartment rental, gave his testimony over Zoom. In addition to the issues he had already raised, he said he told the visitors about persistent and grave disparagement of Pope Francis at the monastery, the presence of inappropriate guests, and the allegation that Kirby frequently gossiped to community members about matters he had learned in spiritual direction.

After their visit, though, things moved quickly. On June 25, the monastery was given a five-page report from the visitors. The report praised the monastery as a “place of prayer, a place that is a center of peace and retreat.”

It made several suggestions: That the monks put more funds in reserve rather than spending income as it came in, that the monks find income streams beyond donations, that the monks better budget and track their expenses. It suggested changes to respect the healthcare privacy of monks, and urged “maintaining proper boundaries between the internal and external forums,” namely, separating the roles of superior and confessor.

It urged more broadly that the monastery attend better to the organization norms of its canonical and civil statutes, holding chapter meetings, recording minutes, establishing a formal “seniorate” — a staple of Benedictine life. It also urged an annual safe environment training for monks.

But the report did not address the issues Andersen had raised about Kirby.

“The visitors did not address the central things that I reported,” he said.

Bishop Deenihan told him that the visitors concluded that Kirby had been “imprudent,” and “lacked proper boundaries,” but that his behavior didn’t meet the level of sexual abuse.

Andersen did not understand why allegations of serially “imprudent” harassment seemed unimportant.

And he said he did not understand why, given the issues he and others had raised, Kirby was confirmed as the monastery’s prior after the visitation. He wondered whether the provisions of Vos estis lux mundi, concerning abuse of office and imbalances of authority and power, had been given any serious consideration by the visitors at all.

Andersen noted that Bishop Deenihan reported Andersen’s allegations of harassment to the police — but only, he said, after Andersen had written to the apostolic nuncio to report Kirby’s harassment. Still, the bishop’s police report would seem to indicate that Deenihan understood the seriousness of the issue, he thought. How could the bishop report allegations of misconduct to police while confirming the accused in a leadership position?

Andersen said he has come to believe that Deenihan avoided acting on his allegations against Kirby because the Meath diocese “has been derelict in its duties in overseeing Silverstream Priory.”

That, he said, would motivate the bishop to avoid acknowledging or addressing the problem.

“He has a very embarrassing situation on his hands. He has made bad decisions, and the diocese has, and they’ve just compounded over and over.”

A spokesman for the Diocese of Meath told The Pillar that Deenihan was unable to comment on any aspect of the visitation, “as matters are still ongoing.”

Whatever the reason, Andersen said he was told in June 2020 that the visitation would “remain open,” which meant that he could not return to the priory. He decided to return to the United States.

Waiting for resolution

Kirby resigned as prior of Silverstream Abbey in July 2020, as news of the visitation and the allegations against him began to emerge in blogs and on social media in Ireland. Abbot Brendan Coffey of Glenstal Abbey, who led the visitation, was placed in temporary charge of Silverstream. After a brief absence, Kirby took up life in the monastery not as superior, but as an ordinary monk.

But the visitation was not formally concluded, Andersen said.

Andersen returned in June 2020 to live with family in the United States. He says Coffey eventually told him that he would not be able to receive any faculties or financial assistance unless he agreed to live at a monastery in France while he waited for Silverstream’s visitation to conclude — a move made impossible, he said, by the travel restrictions of the pandemic.

And Andersen felt his allegations were being ignored, or swept under the rug.

In September 2020, a spokesman for the Irish bishops’ conference told the National Catholic Reporter that sexual misconduct allegations were made against Kirby, but they did not pertain to the visitation, and were made by a monk no longer in residence at the monastery.

Andersen was that monk, and his allegations did prompt the monastery visitation, correspondence from Deenihan confirmed. Further, Andersen was no longer in residence at the monastery because, while still a member of the monastery, he was not yet permitted to return. His departure was not a singularly voluntary decision, Andersen insisted — he hadn’t asked to be forced out, he said.

In the autumn of 2020, Andersen briefly took up residence at the Orthodox seminary in New York where he had conducted graduate studies. He wasn’t really sure where else to go — Silverstream Priory was the nearly whole of his experience as a Catholic, and as a priest.

Andersen had no faculties for ministry; and he learned that the Archdiocese of New York declined to give him priestly faculties after a call from Bishop Deenihan. He said he realized the Meath diocese was unlikely to permit him to exercise priestly ministry anywhere.

That, Andersen said, is when he began to believe he was being punished and exiled for sounding the alarm at Silverstream.

He said Coffey began to accuse him of leaking information about Silverstream to Irish bloggers, and of misusing Silverstream funds — both of which, he said, are untrue.

In October 2020, Br. Elijah Carroll was appointed the superior at Silverstream, a highly unusual move, since the monk is not a priest.

Coffey told The Pillar that he has “had no involvement with the Priory of Silverstream for many months and so I am not in a position to respond to your questions.”

“Canonical Visitations are confidential to the community visited and so I am not at liberty to discuss this with you. You will need to contact the community of Silverstream Priory directly for a comment on their Visitation,” he added.

Coffey did not clarify whether visitation remains ongoing, or whether it has been concluded.

Canonical charges

Irish police and non-profit financial regulators continued investigating the possibility of wrongdoing at the monastery, some of which, Andersen has been told, will be passed onto prosecutors for possible criminal charges. Andersen said was told in recent months he might need to testify in criminal proceedings, especially regarding financial misconduct.

But within the Church, Andersen said he was in a holding pattern — no ministry, no permanent home, no sense of whether he could ever return to the monastery. With no other options, he eventually attempted to move to the French monastery in December 2020, but travel restrictions prohibited it. He moved back in with family members in March 2021.

The next month, he said, he received some disturbing news.

In a letter from Deenihan, Andersen was notified that he would be the subject of a Vatican investigation: He was accused of indirectly violating the seal of confession, a matter under review by the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith. The letter included no details about the allegation, which Deenihan called a “most difficult situation for any priest.”

Andersen was shocked. He said he had never violated the seal of confession. Of course, it would be difficult to prove that, he knew. He said the bishop mentioned that if he petitioned to be laicized, the matter would be closed.

The priest does not want to be laicized. And he is sure he had not violated the seal. He told The Pillar the charges are false, that they have been “weaponized” against him to induce him to leave the monastery permanently.

He thinks it’s possible that information he shared with the police and with his bishop about Kirby is believed to have come from the confessional. But he insists that’s not the case. And he says he wants a chance to face the charges— whatever they are.

Violating the seal of confession is a serious crime in the Church. When a priest directly betrays a penitent by revealing his sins to other people, he can be excommunicated and face other serious consequences. An indirect violation of the seal — in which a priest gives some information from which one might suspect what was said in confession — is also a serious crime, but it doesn’t lead to excommunication.

A priest accused of indirectly violating the seal — like Andersen — is sometimes required to take a retreat, or a class in sacramental theology, to do some kind of penance, or even to serve out a period of suspension. But he usually returns to ministry.

Andersen, though, doesn’t know what will happen to him. Since he was notified in April that he stands accused, he told The Pillar he’s been able to get no information about what will come next, what the substance of the accusation actually is, and what he can expect. He says he has no way of knowing whether this is another consequence of blowing the whistle at Silverstream, and no one will tell him anything.

“This is the culmination of a bunch of this nonsense for about a year now,” he said.

Neither the Bishop of Meath nor the apostolic nuncio to Ireland answered The Pillar’s questions about the accusation against Andersen.

‘Perps’ Corner’

Andersen told The Pillar that he wants to preserve his priesthood, and he isn’t sure where to turn. Whatever is going to happen, he said, he’d like to see it happen soon. He said he feels like he’s been placed on indefinite hiatus, with the hope that he will just go away.

The priest also said he hopes that his story might spur better canonical protections for whistleblowers within the Church, especially priests, and raise awareness about the kinds of dysfunction that can emerge when new and untested religious communities develop with little guidance from the Church’s centuries of experience.

In the meantime, Andersen says he’s been defamed.

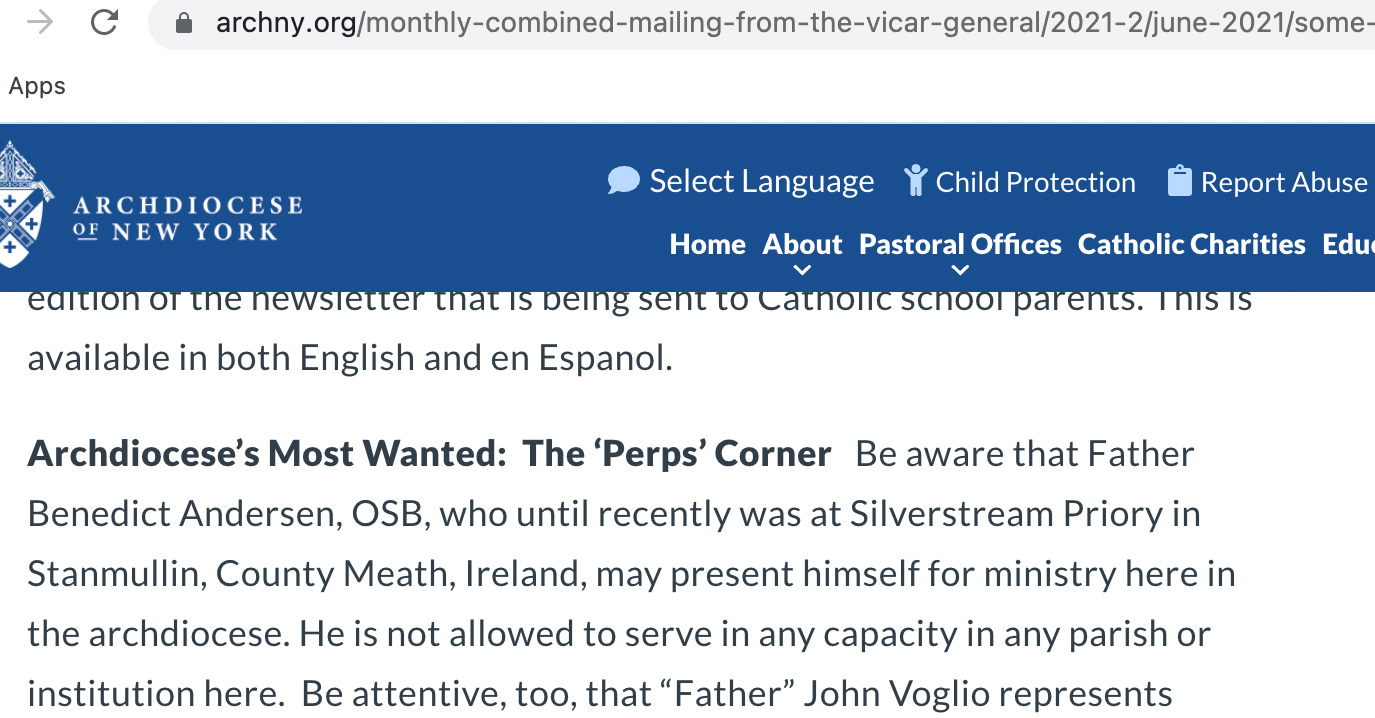

The priest was disturbed this month when a friend sent him a link to a newsletter posted online, for priests of the Archdiocese of New York. He found his name listed under a heading he found unusual: “Archdiocese’s Most Wanted: The ‘Perps’ Corner.”

A short note followed: “Be aware that Father Benedict Andersen, OSB, who until recently was at Silverstream Priory in Stanmullin, County Meath, Ireland, may present himself for ministry here in the archdiocese. He is not allowed to serve in any capacity in any parish or institution here.”

Andersen told The Pillar he found the message “very odd.”

While Andersen was shaken, the priest speculated that Irish ecclesiastical officials gave false information about him to officials in the Archdiocese of New York. He did not, after all, believe himself to be a “perp.” He found the description insulting.

“It has the effect of defaming me,” he added.

Was he defamed? What prompted the message? It’s hard to say. Officials of the Archdiocese of New York have not responded to questions about Andersen.

But for Andersen, the notice felt like just one more in a series of unexplained events, of humiliations, of crosses in the past year. He said he’s tried to find grace in the sacrifices.

The priest says he’s now waiting for clarity on whether he’ll actually face canonical charges, and whether he’ll have options to serve in priestly ministry. He continues to offer Mass privately, and to remain faithful to his breviary. Far from his monastery, he tries to live like a monk.

“I’m going to have to figure something out,” Andersen said. He wants to be in ministry as a priest — not at Silverstream, but somewhere.

But whether that will happen — and whether he’s really facing exile for blowing the whistle — remains unclear. The situation, like much of Andersen’s experience in the Church, is unusual.

Andersen accepts that. But he says he loves his priesthood. He says he loves the Church. And, he says, he’s not sure how long to wait for something to change.