Happy Friday friends,

I want to start with a note of thanks. Many of you have either received (or will shortly) a renewal notice on your Pillar subscription.

Many of you started supporting us this time last year - right as we were launching. It was a tremendous outpouring of confidence, as we jumped off a professional cliff, with little certainty about whether this project would fly.

We’re obviously still here one year on, and it’s stating the obvious that we wouldn’t be without you. So, sincerely, thank you.

We have worked hard to make good on our promise of long-form and investigative journalism about the life of the Church which goes beyond the daily news cycle.

Be it through our original polling, data analysis, topical explainers, or behind the scenes coverage of the US bishops’ conference and Vatican affairs, we’re bringing you news you won’t find anywhere else.

We have a long way to go to make sure The Pillar is on steady ground. We also have cool plans for our next year, and new ideas and projects we want to bring on line.

Those of you who have been with us from the start, or joined us along the way, have made this happen — and we won’t get much further without you. Thanks for sticking with us.

And, of course, to the majority of you reading this who aren’t yet paying subscribers, please consider joining us. You’re getting this newsletter because we want our work to be freely available, and because we believe what we’re doing has value. If you agree, please help us keep going.

Alright, enough of that, let’s get in with the stuff you’re paying for.

Quick links

In Rome yesterday, Archbishop Rino Fischella, president of the Pontifical Council for the New Evangelization, announced the theme for the 2025 Jubilee Year.

The theme is “Pilgrims of Hope.” Which sounds nice, I guess. I’m not sure there is much else to be said about it.

What is interesting is the history of Jubilee years: why we have them, how they work, and how they have evolved over the last thousand years. So, we have an explainer for you about that. It is interesting history, and, somehow, it involves liquor and cherries, too.

—

One of the more interesting institutions in the Church in the U.S. is the Pontifical North American College, the American seminary on the Janiculum hill overlooking the Vatican. The NAC is a unique place, where students from around the country receive their priestly formation with a broad, global perspective on the Church.

The seminary announced this week that the outgoing rector is going to be staying on for an additional six months, after his term ends at the end of the month. The search for his successor is not yet concluded. As you’d imagine, leading a pontifical college in Rome with a board made up of fifteen US bishops is kind of a big deal, and the outgoing rector is normally a safe bet to become a bishop somewhere.

We asked around about the delay, and it seems the board have their man. But by trying to get him confirmed in a hurry they ended up creating something of a delay for themselves with the Vatican.

It’s interesting — read all about it here and stay tuned.

—

People ask a lot about what makes a Catholic school succeed, and even about how to define success. And over the course of the last 12 months, we’ve looked at a few different possible answers to that.

In conversations about Catholic schools these days, you hear a lot about adopting a “classical” curriculum, rooted in great books, traditional math skills, and heavy on human formation.

In this week’s conversation with an interesting person, Charlie Camosy sat down with Tommy Curtin, the headmaster of a school that “went classical” three years ago, when it wasn’t certain the school would keep going at all.

Today, Our Lady of the Rosary has nearly doubled in size, and grown to include a high school. It’s a magnet for families, some of whom are moving to the parish from around the country just for the school.

The classicist in me would like to assume this is all just the natural effect of children learning Latin, but there’s probably something more going on.

Curtin talks about the culture of Catholic schools as their “hidden curriculum.” He has some interesting insights into how we should understand and look for school culture.

“So many dioceses congratulate themselves because the accreditation report comes back and, lo and behold, their schools receive high marks for Catholic identity. This is a Pyrrhic victory.

Catholic identity is largely about the work the school itself performs – weekly Mass, Lenten retreat, religion class – not what the children and their parents actually experience. Bishops and pastors need to do what is necessary to make their schools models of Catholic culture, where the truth, goodness, and beauty of Jesus Christ are integrated not simply through the practices of the school, but through the persons of the school. All of them.

The culture of the school is what evangelizes, what creates disciples.”

I really like the understanding of Catholic schools as, first and foremost, centers of evangelization. You would think it’s an obvious or intuitive concept, but not necessarily.

Catholic schools in much of this country, especially parochial ones, were largely founded as a place for Catholic families to send their children at a time when the public schools were more or less explicitly anti-Catholic. Kids were catechized, sure, but I am not sure teachers would have spoken of themselves as evangelists in the classroom.

In more recent years, largely because of their academic excellence, Catholic schools have drawn increasing numbers of students from non-Catholic families. Schools often speak of a tension between preserving a school’s Catholic “ethos” or “tradition”, whatever they are, without trying to force the faith on students.

Whatever academic curriculum a school is following, Curtin’s understanding of evangelization through an authentic Catholic culture, and how you get one, seems so reasonable to me it’s probably bound to strike some people as controversial.

Anyway, it is a very interesting conversation. Read the whole thing.

Marching into the fray?

Next week is the March for Life here in Washington. It’s the first time the event will take place in person since the beginning of 2020. Last year, the march moved online at the last minute, in the wake of the Capitol riots on Jan. 6.

I don’t claim to know the thinking of the March’s organizers, but I, for one, was rather relieved that the in-person march was cancelled last year.

Why?

Because I’m sensitive to the perception that March for Life had undergone some mission creep in the years preceding the 2020 election. The movement to end abortion has a political dimension, and politics makes for ugly bedfellows. But for Christians, there is always a bit of discomfort with that arrangement.

In recent years, the March’s partisan tone had become more pronounced, especially as the country’s partisanship started hitting hyperdrive. This means, in part, a kind of partisan selectivity that didn’t always play well in the court of public perception — the “changing hearts” element of the whole affair.

When for example, past speakers at the March willingly adopted the line about Trump being the “most pro-life president in history,” despite, for example, his voracious use of the federal death penalty, things moved beyond an understood political alliance to an endorsement — one that has demonstrably left a lot of fractures in the pro-life movement, and a perception that it is entirely the wing of a political party.

And last year, after the January 6 Capitol riot, that perception would have been all the more acute — the March might have easily taken on the tone of another “Stop the Steal” rally, or been perceived that way on the livestream — to no one’s benefit.

Consider the pro-life speakers who were, by their own account, “mildly in the fray” on Jan. 6 last year. It’s my personal opinion that having them back on Capitol Hill two weeks later for the M4L, even just as faces in the crowd, would have done the pro-life cause no good, and possibly much harm.

Of course, people committed to ending legal abortion can be grateful for political gains where they have been made, and hold disparate opinions on how to make even more progress. And I’m not saying everyone who turns up next week wearing a red hat is trying to alienate someone — in fact I know that isn’t the case.

But building a real national culture of life is a work of conciliation, not provocation, and if we do see real power to limit abortion turned back over to the states, rolling out new protections for the unborn nationwide is going to require real coalitions — and political compromise.

Pro-life Democrats may be political unicorns at the federal level, but that’s absolutely not the case at the state level — look at Louisiana.

That’s probably why in California, where passing even the faintest kind of pro-life protections in law would require serious political ability — statesmanship, effectively — the Archdiocese of Los Angeles has chosen to make its pro-life march, called OneLifeLA, a cultural event, focused on building a culture of life, not making statehouse stump speeches.

The idea is that if pro-life lawmakers are going to get anywhere in the state, they have to be strategic, and they have to be careful not to carry the perception that their pro-life convictions are only as deep as their party loyalty card. OneLifeLA’s focus on sowing the idea that human dignity — for the unborn, among others — is one that everybody can rally around, and everyone should.

Is it working? Are pro-life laws being passed in California? Not as such, not really. But the thought, at least, is that the strategy is going to be more effective than whatever else is available on offer.

Even in New York, polling repeatedly shows that most self-identified “pro-choice” Democrats don’t agree with their state’s unfettered abortion protections. There is still a conversation to be had at the state level — one that could save lives.

But it’s not a conversation that will get far if the popular image of a pro-life speaker is still stopping the steal, and jumping, however mildly, “into the fray.”

A process story

With the possible exception of Elon Musk, what is said on Twitter doesn’t matter nearly as much as people on Twitter would like you to believe.

That being said, sometimes social media does provide a neat illustration of an issue, and such was the case this week with the USCCB and the Synod on Synodality.

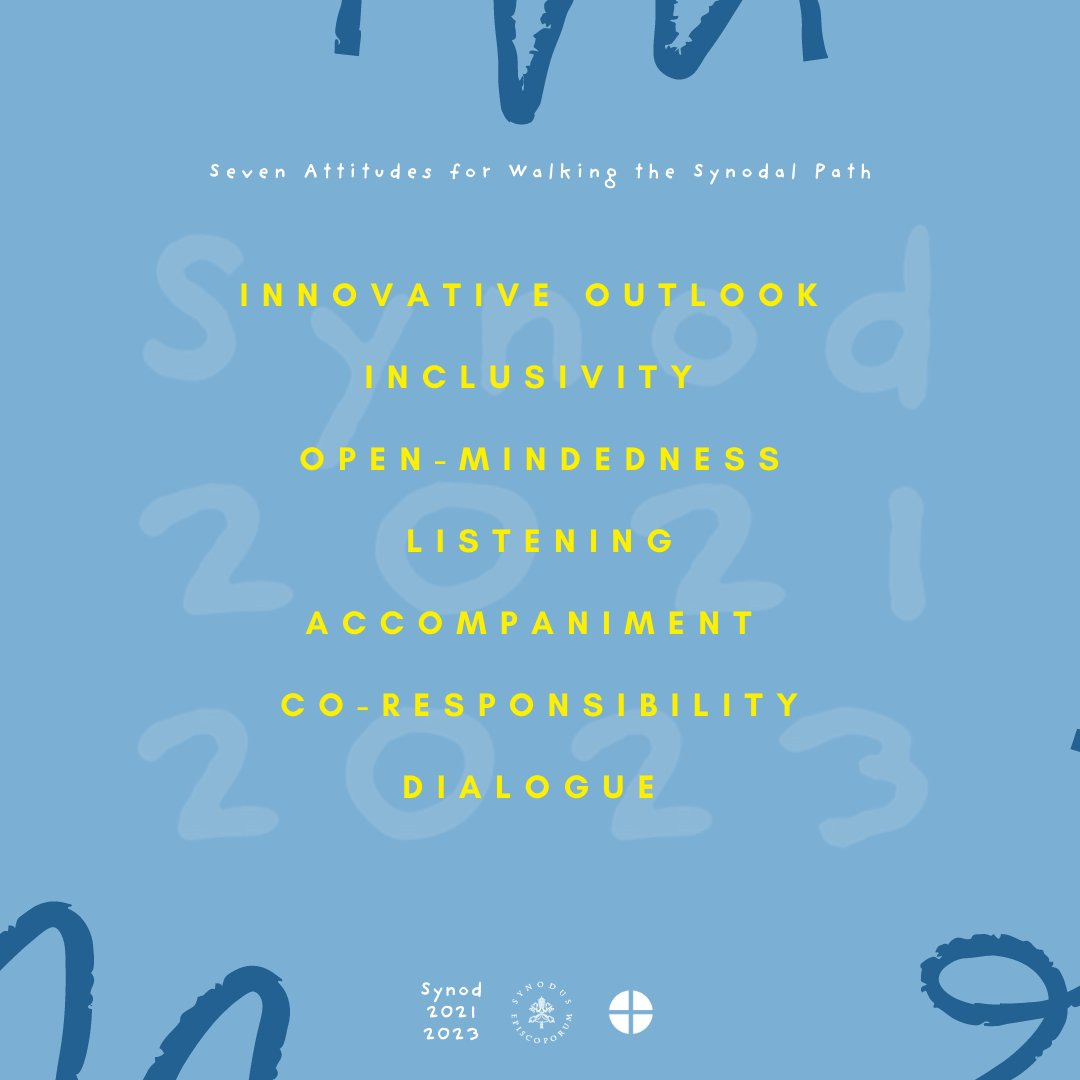

The conference’s official account tweeted out a list of “attitudes” to help us “continue our synodal journey together,” and invited people to offer their feedback on which of them they found inspiring.

The feedback came, and it would be fair to say inspiration was not lacking — the “attitudes” were creatively and universally slated for being insipid, vacuus, HR speak.

Now, an ill-judged graphic in an unpopular tweet is hardly a barometer for judging the conference’s synodal efforts. So in the interest of fairness, we asked for a conversation with the USCCB’s synodal team, to flesh out what they’re doing, and how, to support US dioceses gear up for the global Church event.

Many have since noted that this kind of management speak is of a piece with many of the official preparatory materials coming out of the synod’s secretariat in Rome, which shares the blame a bit. But doesn’t exactly make anyone more inclined to trust the process.

It’s easy to make fun, and easy to shrug off as the kind of maladroit marketing which often comes along with Church programs. But, especially when we are dealing with a nebulous process about a nebulous concept, the messaging can easily come to define the event.

Back in November the apostolic nuncio, Archbishop Pierre told the U.S. bishops that the synod on synodality is not, despite what you might have heard, a meeting about meetings.

However, as Pope Francis said just this week, it is a process about the process — synodality is about being together and fostering communion. It is about listening, hopefully, to what people need and what the Church has to offer them: eternal life, in both cases.

It’s all well and good to call for “dialogue” and tweet about a #ListeningChurch, but, when the response to simple questions is a lengthy paragraph of abstruse jargonese, the impression some Catholics will take away is that no one was #Listening to the question in the first place.

More to the point, if an entire process is supposed to be about fostering communion and authentic communication, but only speaks in the language of management consultants, many Catholics will reasonably ask if the synod is being lived as a real ecclesiological process, or as marketing gimmick.

When the process is your whole story, how you pitch it matters a great deal. You’re unlikely to convince people to show up expecting to hear the voice of the Holy Spirit if you can’t even sound credibly human.

See you next week,

Ed. Condon

Editor

The Pillar