Pillar subscribers can listen to this Pillar Post here: The Pillar TL;DR

Hey everybody,

Today is the feast of Pope St. John Paul II, and you’re reading The Tuesday Pillar Post.

It seems appropriate to note today, here at the synod of synods, that Pope St. John Paul II signed in his pontificate 13 post-synodal exhortations, after 13 synods of bishops in Rome.

Some of them you’ve likely read before, like Christifideles Laici or Familiaris consortio.

Some might be less familiar, like 1984’s Reconciliatio et paenitentia after a synod of bishops on reconciliation and penance. It’s worth reading.

In the text of that exhortation, John Paul II developed the theme of “Christ the reconciler,” who, “in the paschal mystery of his death and resurrection,” is “the cause of man's reconciliation in its twofold aspect of liberation from sin and communion of grace with God.”

Warning against losing a sense of sin, the late pontiff also warned practicing Catholics, people like you and me, against a kind of complacency, a sense that we might be “good enough,” giving up on the path of conversion, on the practices of repentance and earnest penance.

It’s a real temptation, if we practice the faith, to settle for less than holiness, to grow comfortable living day after day with certain sins, certain attitudes, certain “thorns in the flesh,” and even to believe perhaps that God won’t free us from them. To believe even that, in the context of our practice of our faith, and our service to the Kingdom, our sins are offset, or insignificant, or that, in the grand scheme of things, they don’t really matter that much to God

The pope is stark in his assessment of that view: “There is no middle way between life and death.”

But John Paul II’s style wasn’t about just fire and brimstone. He was serious about sin, and that it separates us from God, deadens our consciences, warps our judgment, and harms our relationships. But he was also serious about the prospect of holiness.

If you lived in the time of John Paul II, and you remember him, you almost certainly remember him saying that you — you! — could be a saint. Are called to be a saint. That God made you for holiness, and that the Church and the world need your holiness.

When I was young, and listening to JPII here in Rome, or at World Youth Day, or his in visits to the U.S., I saw all that talk about holiness as romantic — as an invitation to some grand and great missionary adventure. And, indeed, I think God has called me on some grand adventures.

But as I get older, and realize how much of holiness is in the banaltiy of day-to-day conversion, I’m struck by the witness of an old man, John Paul II himself, who had been through a great deal of life, who had likely tried and failed as many times as me, and who remained convicted that in every daily struggle, every little sin, Christ could — and would — be the source of real freedom.

“In order that in the not too distant future abundant fruits may come from it, I invite you all to join me in turning to Christ's heart, the eloquent sign of the divine mercy, the ‘propitiation for our sins,’ ‘our peace and reconciliation,’ that we may draw from it an interior encouragement to hate sin and to be converted to God, and find in it the divine kindness which lovingly responds to human repentance.”

That’s an invitation worth hearing again. And one worth taking up.

—

As to the news, I’m gonna start with the synod for purpose of thematic unity. But I’d argue that the most newsworthy story I’ll link to today — published this morning by The Pillar — is toward the very bottom of this newsletter.

So plow through the synod stuff, or feel free to skip ahead, according to your fancy, and come back to the synod later. The synod will still be there. The. Synod. Will. Always. Be. There.

News from the synod

Ed and I are both in Rome right now as we enter the closing days of the synod on synodality. I (mercifully) go home tomorrow, after nearly two weeks of covering it.

The synod on synodality is meant to focus on how the Church can better discern the will of God by prayerful conversation and consultative discernment ahead of decision-making. This could mean listening to people who don’t practice the faith or are disaffected from it, in order to better understand how to proclaim the Gospel to them. Or it could mean listening to practicing and engaged Catholics, to hear how the Holy Spirit is moving in their life, or how they might speak prophetically to, and with, the Church’s leaders, her pastors and bishops.

In principle, I can think of few people who would not support those ideas. But the synod on synodality has been controversial, from the beginning, because of fairly widespread perceptions that the listening is selective, or that what some people have to say is not important enough even to be well-heard, well-documented, or well-considered. This has led synod participants — left and right, in a bit of horseshoe theory — to conclude that the synodal process might do some listening, but that the outcomes are predetermined.

For some delegates here in Rome, that sense was amplified after last October’s month-long meeting, when Pope Francis decided to take a bunch of controversial issues which had come up, and to bracket them into off-site study groups, working outside the main of the synod on synodality.

One of those groups was meant to focus on the role and place of women in ecclesiastical leadership positions. And for some delegates and outside observers, that group was seen as a place where the prospect of women’s ordination — at least to the diaconate — would be discussed.

While Pope Francis has said “no” to women deacons a LOT of times, there are folks who hear “no,” and think “not yet,” and some suspected this study group might even move “no” to “maybe.”

So they were aggrieved on Friday, the day synod delegates had been invited to a meeting of the study group, where they expected they’d hear a progress report of deliberations, and be able to give their own feedback.

They were especially aggrieved that Cardinal Victor Fernandez, prefect of the Dicastery of the Faith, didn’t show, while they had been expecting him to be there.

On Friday night, as The Pillar reported, Fernandez apologized in a message to synod delegates, saying there had been a miscommunication, which had led to misunderstanding, and that he would meet with them this week.

—

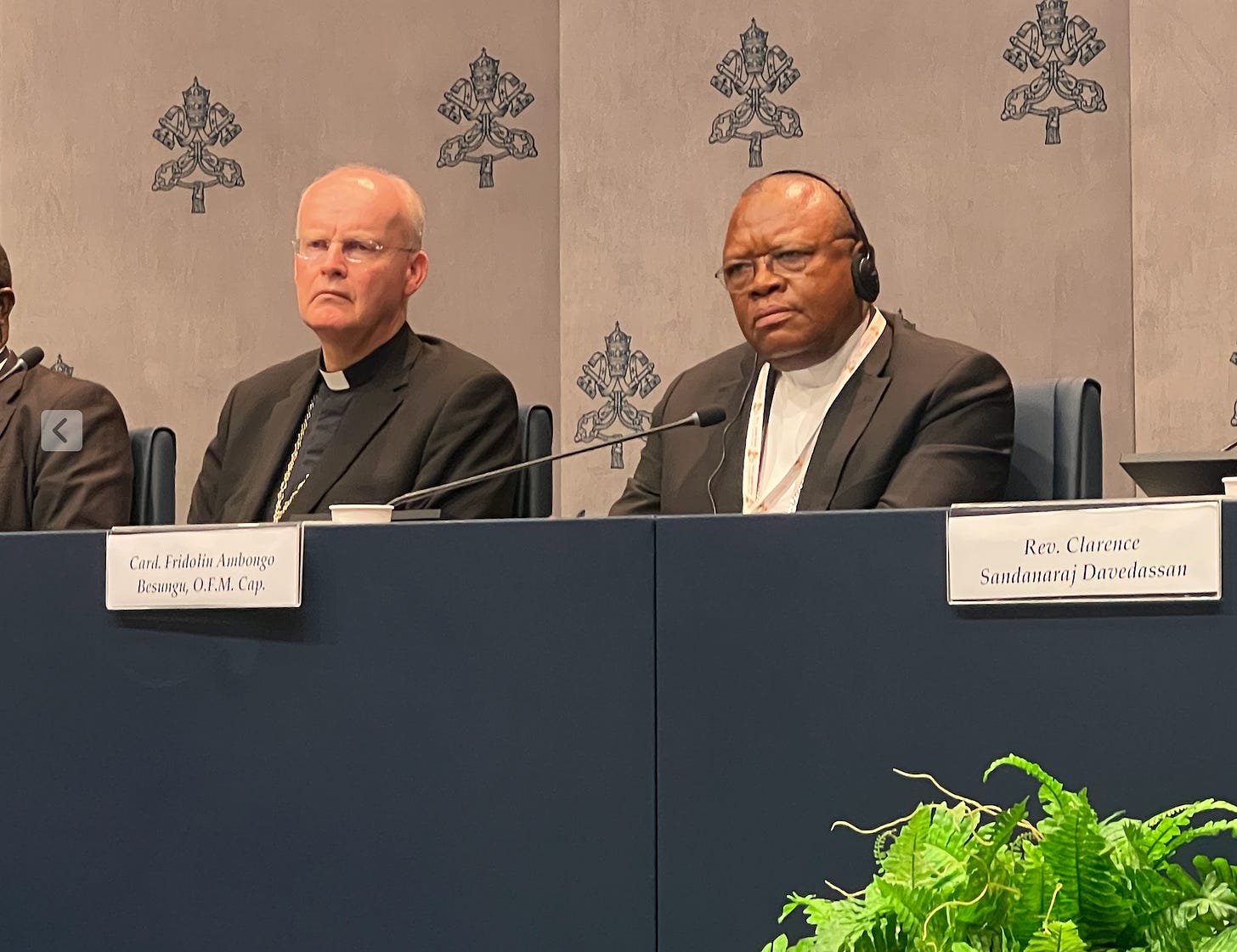

On Monday morning, synod delegates told The Pillar that Fernandez addressed the synod, explaining to them that while he would meet with them this week, he wanted to emphasize that Pope Francis had given a firm no to the sacramental ordination of women as deacons — in line with the theological implications of John Paul II’s Ordinatio sacerdotalis.

Fernandez said his group was looking at other ways to understand/promote/encourage roles for women in the Church’s leadership offices.

And I’ll point that after The Pillar published that report Monday, the Vatican’s press team read out a copy of Fernandez’ remarks during the afternoon press conference, confirming our reporting.

At that same press conference, I asked Sr. Nathalie Becquart, undersecretary to the synod of bishops, to talk about the challenges women face in taking up non-sacramental leadership roles in the Church’s decision-making bodies, in bishops’ conferences or diocesan chanceries. I pointed out that Sr. Nathalie herself has had a great many such roles, as have other women at the synod.

Importantly, Sr. Nathalie noted the cultural challenges for women in ecclesiastical contexts — the ways in which women’s contributions, ideas, comments, can go overlooked or unheard without awareness of that problem. And she said that in her experience, that’s not a uniquely Catholic problem, but it is a real one. For my part, I don’t think that point should be lost or overlooked among all the much more controversial talk of women’s ordination.

It is true that women working in chanceries or bishops’ conferences, or similar institutions, can face real cultural challenges that go overlooked. If you don’t believe me, just ask them. And in my experience as a longtime senior diocesan staffer, bishops benefit immensely from hearing the perspectives of both lay men and women when they’re making decisions. In fact, hearing those voices, instead of only clerical voices, often prevents bad decisions from being made.

That’s not a left-right thing, either.

Some of the bishops I’ve known who are most intentional about hearing the feminine genius, so to speak, in their consultative circles, are quite theologically conservative. And some of the least consultative bishops I’ve known — and I’m talking about being consultative of anybody — have been so-called theological “progressives.”

So if the synod was talking about creating cultures where people are actually heard — and if we actually trust that our baptism means that we can meaningfully contribute to the Church’s life — then we should take seriously that there is a lesson there for ecclesiastical leaders.

Nevertheless, I’m not sure that’s the central part of the discussion about women at the synod.

According to The Pillar’s sources, while delegates discuss today the draft text of their final recommendation document to Pope Francis, there have been numerous interventions today from the floor, which continue to focus on calls for the ordination of women — some of which even say that credibility of the synod is impugned by an absence of that topic in the draft synodal document. There have been multiple interventions to that effect, I’m told.

In that sense, the synod ends just as it begun: with accusations of predetermined outcomes, issues going unheard, and complaints that what people have had to say is not what’s going into the document.

It is not clear whether any of those interventions will mean a proposed amendment to the text, which would be voted upon later in the week.

And on the whole, I should mention that sources say the draft text on the whole, which was present onday afternoon to synod delegates, takes up the framework of the Christian mystery for explaining synodality and its ends. And the document is reportedly focused mostly on the structures of the Church, and ways in which to more frequently incorporate synodal discernment and prayerful consultative conversation into decision-making processes. It is reportedly a structural document, more than anything else.

But it occurs to me that the expressions of discontent — at the beginning and at the end of this long, long process — challenge a central notion of the synod on synodality. I’ve heard synod organizers say, time after time, that “people just want to be heard.”

The idea is that if people feel they’ve been really listened to, they’ll be more and open and accepting to decisions they wouldn’t otherwise support. Hearing a person, the synod says, is a way of “encountering” them — and that’s what people want, to be encountered.

I’m not so sure that people just want to be heard. They also want people in authority to agree with them, and naturally so, if they’re convicted that they’re right.

That poses one of the limits to the very idea of synodality — it doesn’t work to bring on people on board just because they said their piece. If they don’t see results, they’ll often continue to advocate for what they think is right, good, self-advantageous, or whatever, especially if it’s on issue they think is crucial.

People want more than a welcoming process, a nice round table to express their ideas. They — understandably — want results. Few care to spend their time in two months of synoding if they think it won’t lead to outcomes they like. People want their ideas to matter.

And synodality won’t always deliver that. It just can’t.

On the one hand, it seems to me that if the synod document is claiming to summarize the meeting, it should do so accurately and entirely, and people should have a right to expect their views will be included on a transparent and fair basis, without seeing some opinions whitewashed or excised.

On the other hand, the reality is that we’re sometimes we’re right, and sometimes we’re wrong.

Synoding takes place in the context of objective moral norms, and, on many issues, a hierarchical structure of divinely-ordained decision-makers. No one can expect that being heard means their opinion will carry the day, especially if their ideas have already been formally condemned by the Church.

The Church is Catholic, regardless of what any consultation, focus group, or roundtable has to say about it.

That part of any ecclesiastical consulting process is the hard part to swallow — the part requiring humility, grace, and conversion.

I’ll pray for the synod to end on those notes.

Cardinal Mulla pointed out that his bishops’ conference is composed of bishops from Sudan and from neighboring South Sudan. He noted the tensions between those countries, which include decades of intense warfare between them, and eventually a very fragile peace. He also noted the internal civil war roiling Sudan right now, which has displaced millions of people, including the Archbishop of Khartoum.

Mulla said that in his part of the world, the idea of bishops sitting down together to talk — along with other clerics, religious, and lay people — could be very, very powerful. And he thought that kind of synodality might even be helpful to securing more actual peace in the region.

This is a different sense of what synodality could mean. And it’s worth reading.

Here’s an excerpt:

“The remaining question is whether the exercise of these four years will have accomplished anything at all.

To the extent that depends on the delegates, it’s hard to say. Some of those who were once most enthusiastic about the process are leaving likely disappointed, with the feeling that their issues went unheard, unaddressed, or purposefully sidelined. Some of those who arrived more skeptically leave with some conviction — more than they might have expected — that ongoing synodal consultation in their local churches is a good thing.

But everyone at the synod will leave tired, and many with the perception that synodality wasn’t what they expected it to be, or what they hoped it would become. And so in the short term, the pontiff’s hope for more synodality in the Church may seem somewhat exhausted, relying on prospective cheerleaders and champions who are themselves just ready to be home, regardless of their sense of the project they’ve just undertaken.

…

Will any of this have been worth it?

Will it address widespread institutional disaffiliation? Declining trust and discontent over Vatican leadership? Diminished trust between priests and bishops? The persecution of the Church in regimes around the globe? The difficulties in proclaiming the Gospel in the affluent and technocratic West, or of sustaining the Church in the poverty of the developing world?

That remains to be seen.”

—

The rest of the stor(ies)

There are things happening in the Church outside of synodality. Some of the quite important.

The stories of these saints are pretty cool. And you can read about them here.

The prayers are open to anyone, and drawn from the patrimony of the Church.

And their pastor says those prayers are sowing peace, in a time of bipartisan national anxiety.

—

The Pillar reported this morning a development in the story of Ariel Príncipi, the laicized Argentine priest who came to international attention after an official at the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith’s voided an instruction issued by the papal chief of staff, to return the laicized priest to ministry.

The development is this: An interview Saturday with the Vatican’s top canon lawyer suggested that Pope Francis could be personally involved in the case — shifting the focus from Archbishop Edgar Peña Parra, to Pope Francis himself.

Why? Well, Archbishop Filippo Iannone of the Dicastery for Legislative Texts pointed out that officials at the Vatican’s Secretariat of State can be legitimately involved in clerical abuse cases, when they act as confidential couriers for decisions reached by other Vatican departments competent to deal with those cases.

But appeals by or for priests laicized for abuse crimes can only be considered by the pope personally, or by others acting under his personal delegation.

In other words, if Peña Parra was acting as a Vatican mailman when he attempted to rescind Príncippi’s laicization, it was seemingly because Pope Francis authorized a process in that regard — even after the priest was twice convicted of sexually abusing minors.

And given that another senior Vatican official, Archbishop John Kennedy, acted unilaterally to void that process, there is now an unprecedented clash between the two most senior Vatican departments — with one of them seemingly acting on the pope’s behalf, and other possibly acting to overturn a decision authorized by the pope directly.

Guys, this isn’t just a technical kind of legal spat between two Vatican departments. This story seems to suggest that Pope Francis intervened to return to ministry a priest twice convicted of sexual abuse — and that a Vatican official stood up to to stop that intervention.

This is a big deal.

This is dumb.

The Guardian reported a couple of days ago that a company called Heliospect Genomics has begun offering couples the chance to test their IVF-created embryos for genetic markers indicating higher levels of intelligence. For $50,000, couples can reportedly have up to 100 embryos tested for supposedly intelligence-predicting genetic markers, which could apparently lead to an offspring intelligence boost of up to six points.

This is evil, because anything involving the segregation of procreation from good ole’ fashioned relations is immoral, and because commodifying desirable human traits, and destroying embryos without them, is the kind of dystopian thing about which bleak fiction has already been written. We can’t say we haven’t been warned.

But in addition to being evil, paying 50 grand for babies that might be a bit smarter is just plain dumb.

First, there’s generally perceived to be about a five-point variance in the measurement of intelligence, which can occur if people take different tests, take them at different times, or when they’re more or less healthy. So intelligence measurement is already best thought of as a range, not a precise marker. And if the range is +/- five points, claiming to add six just doesn’t seem like that big a deal.

The other thing is that while intelligence is shaped by genetics, scientists also think that environment plays a big role in things. And if you’ve got an extra 50 large lying around, I’d think you could afford a museum membership, or a subscription to Le Monde For Kids, or just a weekly trip to the public library.

In fact, just imagine what kind of hellish, helicopter-parent existence a child is in for if his parents spent 50,000 bucks on the prospect that he’d be slightly smarter. Do you think little Eustace is going to be allowed to get his genetically engineered hands dirty with his relatively yokel cousins? Don’t you imagine his parents will demand a refund when he starts getting Cs or, heaven forbid, cutting class? And, oh man, can you imagine having to make small-talk with the kind of priggish little scrub he’d inevitably become?

But there’s another thing. Intelligence correlates, to some degree, with higher earning, but my read on the subject is that scientists are somewhat split on whether intelligence correlates very much to happiness.

Mad geniuses, for example, are never happy — it’s right there in the name. Think about the unhappiness of The Brain, relative to Pinky. Or Van Gogh’s deep depression. Or consider Ed. Condon.

As to the IVF screening, the truth is that offerings like this are still in the realm of snake-oil science. But they’re meant to draw attention to the easier kind of IVF screenings available to prospective parents, the ones meant so that everyone can live with the illusion that our mortality can be tamed and conquered.

I’m talking about the kinds of tests which can — and do — reliably screen out embryos with distinct genetic disabilities, ensuring that the world is ever more free of disabled children like mine.

And let me tell you, a world devoid of people like that is a world devoid of joy.

We’re better off as a society with the children God gives us, whatever their flaws, without this kind of crap. No matter how smart the rest of us think we are.

Anyway, I’ve got to get to the Vatican press conference. Please be assured of our prayers, and please pray for us. We need it.

And here’s a 42,000 piece puzzle, for your enjoyment:

Yours in Christ,

JD Flynn

editor-in-chief

The Pillar