‘It’s all legal!’: How the nuncio installed Detroit’s archbishop by his own decree

With Pope Francis too ill to sign the necessary papal bull, Cardinal Pierre said he was installing Archbishop Weisenburger on his own authority

When Archbishop Edward Weisenburger was formally installed as Archbishop of Detroit last week, the liturgy included an interesting hiccup: There was no papal bull in the building to actually make Weisenburger the archbishop.

While Pope Francis’ selection of Weisenburger as archbishop was announced by the Vatican in February, the pope soon after became dangerously unwell, and was forced to spend more than a month in a Roman hospital for treatment.

As a result, the formal papal bull of appointment, ordinarily required for a bishop to take possession of his new diocese, could not be signed by Francis.

Still, the Mass went on.

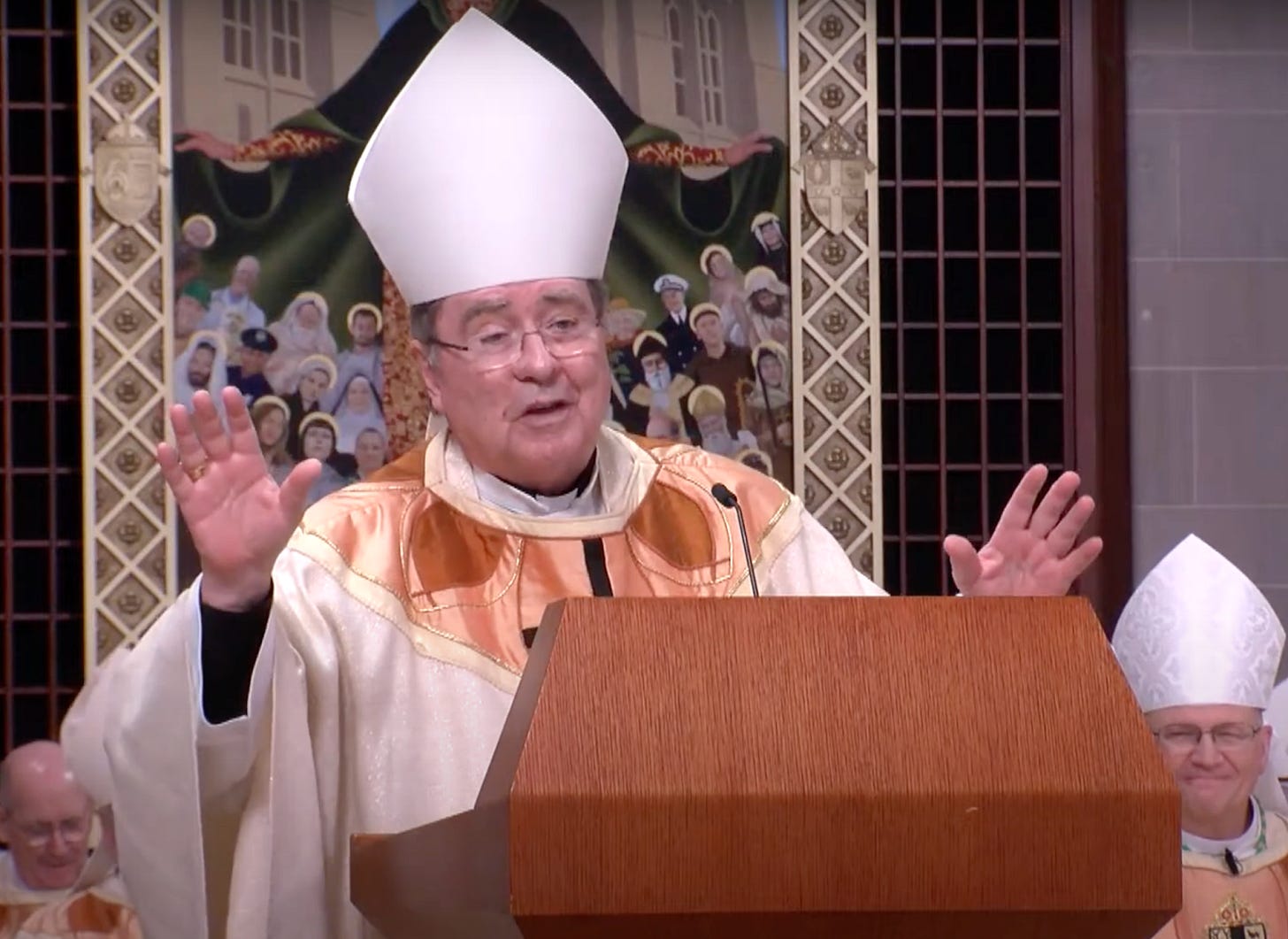

Indeed, during the March 18 Mass of Installation at Detroit’s Blessed Sacrament Cathedral, apostolic nuncio Cardinal Christophe Pierre told the gathered Catholics of the archdiocese that he had prepared a decree of his own to effect Weisenburger’s installation.

While the nuncio jokingly suggested that some canon lawyers might be “worried” by the unusual maneuver, the cardinal actually exercised a little known power granted to his office — shedding light on one of the many ways in which the Church has worked to accommodate the pope’s prolonged illness.

—

When he took to the ambo during Weisenburger’s installation March 18, Cardinal Pierre explained to the congregation that a highlight of a bishop’ installation of a bishop — and indeed an otherwise constituent part of the process — is for the newly arrived bishop to display his papal bull of appointment to the clergy and Catholics of his diocese, most especially the diocesan college of consultors, a body of priests required by canon law to formally inspect the text during the liturgy.

But Pierre explained that couldn’t be done at Weisenburger’s installation Mass.

“I’m sorry,” the cardinal said from the lectern, “because normally I should have showed you the bulla, the final document which is normally signed by the Holy Father. Unfortunately, you know, because of his sickness, the Holy Father was unable to sign it.”

“I cannot read you a document which has not been signed by the pope,” the nuncio explained.

“Don’t worry, he will be a real archbishop,” Pierre hastened to add, to laughter from the assembly.

“Some of you are already smiling,” he said, while explaining that he had himself drawn up a decree for the occasion in his capacity as apostolic nuncio. “Don’t worry, it is all legal,” he assured the assembly. “I can see that some canon lawyers are already worried — I don’t know why.”

The papal bull of appointment, duly signed by the pope, would arrive later, Pierre said, promising to “put it in a museum” so people would be able to inspect it. Instead, the nuncio read from a decree he had himself drawn up.

Noting the public announcement of the pope’s appointment of Weisenburger to the archdiocese and “the papal bull not having arrived,” Pierre said, reading from his own decree, “We, Christophe Cardinal Pierre — that’s myself — apostolic nuncio in the United States of America, using the faculties conceded to us by the Holy See, grant the licence so that the Most Reverend Archbishop-elect Weisenburger may validly and licitly take possession of his office.”

Pierre’s decree provided that it be read and presented to the clergy and the people of the archdiocese in place of the papal bull, and be recorded in the archdiocesan archives “according to the norms of the Code of Canon Law.”

But while the nuncio noted that the move might make canonists “worried,” Pierre’s decision to issue his own decree in place of the papal bull — while certainly an unusual event — is still one foreseen by the law.

The Code of Canon Law provides that a bishop only formally takes canonical possession of his diocese — and thereby is able to exercise the powers of that office — when he “has shown the apostolic letter [signed by the pope] in the same diocese to the college of consultors in the presence of the chancellor of the curia, who records the event.”

“It is strongly recommended that the taking possession of canonical possession be done within a liturgical act in the cathedral church with the clergy and people gathered together.”

In Weisenburger’s case, as the nuncio explained, the bull of appointment had not arrived because it had not yet been signed by the pope, due to his prolonged illness.

Of course, there is no real question about the pope’s designation of the new archbishop for Detroit, given that it was announced by the Holy See press office in the daily bollettino of February 11.

But the fact of the pope’s choice of Weisenburger does not, by itself, give the nuncio legal authority to substitute his own decree in the absence of a formal papal bull of appointment — since apostolic nuncios are not appointed with unlimited general powers to substitute for papal acts of governance.

Instead, the Code of Canon Law lists the functions of “papal legates” — usually designated apostolic nuncios — as primarily non-governing, and focused on forging “stronger and more effective the bonds of unity” between local Churches and the Holy See, and to “assist bishops by action and counsel while leaving intact their legitimate power.”

When it comes to episcopal appointments, the nuncio does have the ordinary function of compiling, vetting, and proposing candidates for vacant dioceses — though not issuing decrees of appointment.

But canon law allows a wide berth of other possible responsibilities for the nuncio, noting that he can “exercise faculties and to fulfill other mandates which the Apostolic See entrusts to him.”

Many of those faculties are listed in the Vatican’s 1986 Index Facultatum Legatis Pontificiis tributarum, which delineates extraordinary faculties to be exercised by nuncios in place of Vatican curial departments, which includes one faculty relevant to Weisenburger’s situation: The apostolic nuncio is given them power “to allow the bishop to be consecrated and to take possession of his diocese before the Apostolic Letter sub plumbo [under the papal seal] arrives.”

Pierre invoked the rarely deployed faculty just days before Pope Francis returned to the Vatican after a five-week stay in Rome’s Gemelli hospital, where the pontiff underwent treatment for double pneumonia.

Francis was discharged on March 23, after briefly appearing at a hospital balcony to greet the crowds, though his voice was weak and he appeared to be unable to raise his arms.

According to the Vatican, while Francis is well enough to return home and is no longer receiving mechanical ventilation at night, he still requires supplementary oxygen. It is widely considered unlikely that he will immediately resume a full working schedule.

This is a great story. Is there a Pillar, Cannon Law bat phone that goes off for such situations?

I always want to know the history of the creation of unusual rules. Was the first poor bishop who could not be installed due to Papal incapacity temporarily sidelined as his diocese remained sedevacante, or did they attempt to do the installation without any proper authority, followed by a mass uprising?