In Venezuela, activists cry foul after reported priest suicide

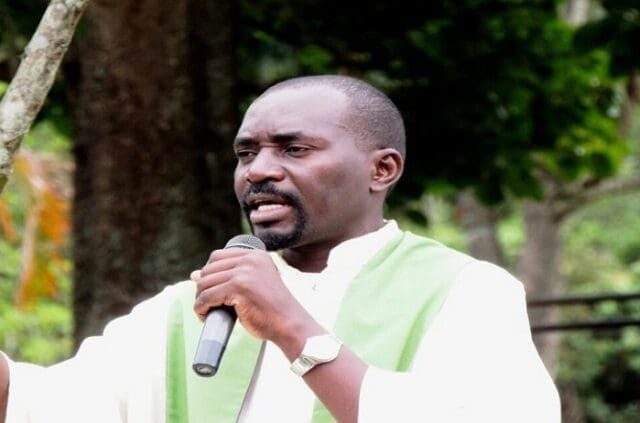

Was the death of Fr. Josiah K’Okal a suicide, or something more sinister?

Venezuelan media reported Jan. 2 that the body of Fr. Josiah K’Okal, IMC, had been found in a wooded area in Guara, Monagas state, near the state border with Delta Amacuro, where K’Okal lived.

K’Okal was born in Kenya, but had lived in Venezuela as a missionary since 1997.

The priest had been one of the loudest voic…