When leaders of St. Charles Borromeo Seminary in Philadelphia decided to move the seminary to a new campus, it was not a simple decision.

And after they decided to make the move, nothing was especially simple either.

Founded in 1832, the Philadelphia seminary has a rich history of priestly formation. Over the past nearly 200 years, it has become not just an educational facility, but an institution in the life of the local Church.

And for 150 of those years, the seminary had been located in the historic Overbrook neighborhood of Philadelphia.

But while the historic campus was beautiful, it was also expensive to maintain, explained Philadelphia’s auxiliary Bishop Keith J. Chylinski, rector of the seminary.

Chylinski told The Pillar that the maintenance on the historic buildings had become prohibitively expensive, and it was no longer financially feasible to keep the 73-acre campus, which was far larger than the seminary actually needed, especially amid financial crises for the Philadelphia archdiocese.

The archdiocese needed to find a smaller and more efficient campus to house its seminary, which is currently forming some 140 men for the priesthood.

But moving an institution is no easy process. It took eight years from the time archdiocesan officials approved a decision to move, back in 2016, until the new campus opened its doors to students this fall.

And along the way, there were plenty of challenging decisions, practical obstacles, and logistical hurdles.

Finding a location

The initial proposal was to consolidate the seminary’s operations onto half of the original campus – and then to sell or lease the other half.

But upon examination, archdiocesan officials determined that the plan wasn’t feasible.

So a core team was established – working under the seminary rector and Philadelphia’s archbishop – to search for a new location that might be a good fit.

The search took several years.

The goal was to find a location on or adjacent to the campus of a local Catholic university. The seminary wanted to maintain its independence — offering its own degrees and not having seminarians take classes at another school. But the hope, Chylinski said, was to save money on shared services, like security, in order to reduce operating costs.

Eventually, the seminary contacted Gwynedd Mercy University, a Catholic college in Lower Gwynedd, just north of Philadelphia - about 20 miles away from the seminary’s previous location. Founded by the Sisters of Mercy, Gwynedd Mercy University has an enrollment of about 1,500 undergraduate students, on a 145-acre campus.

“It's a nice area. It's very quiet. It's a very peaceful setting, so it lends to contemplation and lends to a good, healthy seminary environment, not in the middle of a city or something,” Chylinski said.

The university was open to the idea of selling a portion of its land. So in late 2022, the seminary finalized a purchase of 16 acres on the edge of the university’s property, which included a dorm building. The building was refurbished for the seminarians’ use, and two additional buildings were constructed as well.

The new construction took about a year-and-a-half. In the meantime, the seminary was able to use its old location, which had been sold in 2021 to Main Line Health, a local healthcare system that plans to develop the 73-acre property into a health and wellness campus with senior living facilities and office space.

“When we sold the old campus, part of the agreement was that we could still lease the property for five years, and that allowed us to continue to finalize the search and to construct a new campus. So we were fully operational at the old campus last year,” Chylinski said.

Classes concluded in May 2024, and the buildings in the new location were nearing completion in the weeks that followed.

“It's incredible just to see how quickly it all came together,” the bishop said.

Still, the timeline was tight. Especially to move an entire seminary, in under a month.

“We got our temporary certificate of occupancy by the end of July, which was a great miracle. So we actually had about a two to three week window to move in all of the essentials to be ready for opening day, which was August 21,” Chylinski said.

“It was quite an operation,” he said of the move.

The seminary had contracts with four different moving companies – one specifically for library books, another for office furniture, a third for furnishings from the priests’ residences, and a fourth for moving artwork.

As to the other stuff at the seminary, volunteers and seminarians were enlisted to help.

“We had the availability of 140 very strong young men who could help us carry a lot of things. So they did a lot of work as well.”

“It was a huge enterprise,” the bishop reflected, “and the huge doesn't even describe it, but it was amazing to see how many people stepped up to make it happen. It was truly a work of God's providence, and I'm just so grateful to all of them.”

“We put this under the patronage of St. Joseph, and truly, I am convinced that he performed endless miracles in this whole process.”

To move a library

Moving the seminary’s library into its new location was, in itself, a monumental undertaking.

The process was not as simple as just transporting the books from one building to another, explained James Humble, director of the seminary’s St. Jerome Library.

For one thing, he told The Pillar, the new library space is smaller than the old one – a lot smaller.

“Part of our preparations was to go through the collection, weed out things that were either outdated or things that we didn't quite need to serve our student population in the courses that they take,” Humble said. “We spent about a year before the move doing that, and in doing so, we were able to get it down to a size that was manageable to move and to fit into our new quarters.”

Before the move, the seminary’s library housed around 90,000 books. At the new space, it holds about 60,000.

“We got plans that included the size and scope of the shelving [at the new location.] So we had a better sense of the amount of linear feet that we would have in order to store what we wanted to take, and we tried to measure out what we had, what we wanted to keep of our collection,” Humble said.

Once they knew how much space they were working with, Humble and his two library colleagues went through their entire collection, shelf by shelf and title by title, to decide what to keep. They reviewed all 90,000 books and made a decision about each.

The process was relatively swift in sections that were less directly related to seminary classes – for example, the business section.

“There were a number of works in there that obviously were a bit dated, things that we could do without and replace with, say, just a few more up-to-date titles,” Humble said.

“The harder ones were the areas that I call our core collection, and that's the scripture and the theology sections. You really want to make sure that we have everything that the students are going to need for their studies here. So those we had to be much more picky about.”

In some cases, they would ask a professor to come and give an opinion on a certain title, to ensure that they were keeping the most important ones.

In other cases, the library decided to get rid of its print copy of a book because it had an electronic copy. Humble said the library’s electronic collection currently contains several hundred titles across a number of subject fields.

This wasn’t the first time the library had pruned down its collection. Back before, around 2013, the library actually had around 120,000 books, spanning two floors.

But when seminary leaders first started discussing the possibility of either moving or consolidating – about a decade ago – Humble said, they knew they would be looking at a smaller footprint for the library.

So at that time, they began a full-scale weeding of their collection.

“We had acquired a lot of items over the years that were nice to have, but weren't necessarily pertinent or quite in the mainstream of what we teach here. So during that time, we whittled down our collection… to about 90,000. We were able to fit it all on one floor again.”

Humble said he was glad the library had gone through that first downsizing process, because it made the second round of whittling down books much less overwhelming.

Although the library is now housing half the number of books it once held, Humble stressed that their collection is by no means “a skeleton operation.”

“We really do still have everything that I think students in our undergraduate program would need for any of their general education courses – general world history, American history, art and architecture, literature, several languages and science.”

In addition, he continued, “we have a lot of relationships with other libraries in the area. So if for any of those courses, our students need something beyond what we currently have, either in print or through our databases, we're still able to furnish them with what they might need.”

As for the books they could not keep, Humble said they made arrangements with a local individual who is involved in Catholic grade school and high school education.

“I believe he's going to use them to stock some of the libraries of Catholic high schools and possibly in any new Catholic high school that he might be involved in either here or elsewhere. So we made arrangements in the hope that they would continue to be part of the Catholic education scene in Philadelphia.”

—

After a year of pruning down its collection of books, the library was ready for its big move, which took place in early August. Humble said the goal was to have the library materials in their new place before the students arrived on campus.

To do so, the seminary hired a moving company that specializes in libraries.

Around 20 years ago, the library had undergone a renovation, which required placing books in storage.

“So we already had experience with hiring a library moving company,” Humble explained. “Many of these companies will come prepared with movable carts, whereby they can simply transfer the books as they are set up on the shelves to carts, and then move them in, keeping them in order, moving them to a new location.”

“It was quite an efficient process. They had a very large number of movable carts. They had quite a crew with them. They kept everything in order, and they had just packed them all onto these very large trucks and brought them over here…did a couple trips back and forth, of course, but they were able to get everything on our shelves just in time.”

The movers packed up everything in order, shelf by shelf. But the shelves at the new campus were longer than those at the old campus, so placing the books in their new location was more complicated than simply unloading them in the new space.

Humble said he went and personally marked each of the shelves in the new library with a bookend to designate the amount the shelf he wanted filled.

He wanted to leave some room on the shelves for future growth. So he did the math, based on the total number of linear feet needed for their current collection, and the amount of space allotted on each shelf.

“It turned out to be pretty well exact,” he said.

Humble said he had learned the importance of math and measuring from the previous library director, who had overseen the earlier renovation of the library and the first weeding out process.

“She emphasized to us the importance of measuring ahead of time, doing all the kind of mathematical work, of measuring what you have, measuring the total amount of space that you have, and working out even, if you can, where particular sections begin and end and so on, so that you have a tangible set of markers for making sure everything fits.”

Initially, Humble was unsure how long it would take to move 60,000 books to their new home. He said he speculated it might be a week or two, maybe more.

In the end, though, the process took just four days.

“Once we were set up here, we had about a week before the students came back for the new semester. So it worked out very well.”

Humble said it was edifying to see the final results of the big move.

“I remember standing on concrete floors, looking through windows with no window panes in them, and just wondering if we'd be able to fit the things that we wanted to bring here. I had my doubts even up to the very final weeks,” he acknowledged.

“That was partly because I hadn't seen it with the finishings...you're kind of shooting in the dark for so much of this time when you're making these plans,” he said. “You wonder if it’s all going to be possible.”

But in the end, the move was successful, even with a few hiccups.

“There was one part of our collection that I was anticipating having a little more space than I actually did, and that was not because of the architectural plans or anything, it's just that I was expecting to have a few more shelves than I did. So we had to kind of recalibrate our plans for that particular section,” Humble said.

But overall, the move went smoothly and the library staff – like the rest of the seminary community – is settling into their new home.

“We've been, alongside our normal library operations, making sure everything in the collection is firmly in place,” he said. “We should have that done within the next few weeks.”

Once everything is settled and running smoothly, the library will be open to the public, as it was at the previous location.

Artwork: Moving, selling, donating

Another major part of the move was to decide what to do with the vast array of artwork at the old seminary.

Because the new space was smaller, it would not accommodate everything.

So an art committee at the seminary was commissioned to catalog and audit all of the artwork– including paintings, statues, furniture and more – and to consider what the smaller space at the new campus would allow in terms of transferring artwork.

There was a polling process in which employees and members of the seminary community were asked which pieces would be the most important to retain.

The committee decided that it would be appropriate to sell much of the remaining art, and use the money toward the costs of the seminary move.

Committee members determined which pieces should be sold and created a website of everything that would be available for sale.

That whole process took a few years, said Maria Stumpf, who oversaw the art relocation process.

Stumpf told The Pillar that in total, the sale included some 500-600 pieces of art from the old seminary, including altars, pews, and stained-glass windows, as well as statues, paintings and other images – both religious and secular.

To set prices, the seminary relied heavily on an assessment of its artwork that had been performed about five years ago. Stumpf said some of the prices were adjusted because they knew churches and other potential buyers would be unable to afford to pay the full price.

The seminary was also willing to negotiate with interested buyers, she added.

She said there were a number of pastors who had graduated from the seminary years before, who were very excited to purchase a piece of art for their parish.

At one point, she said, a priest purchased a beautiful round painting of Mary from the chapel. He didn’t know what he was going to do with the painting, but he loved the image and was overjoyed that he could purchase it.

A while later, the priest’s parish was undergoing renovations, and he realized the image would fit perfectly in the newly remodeled front of the church.

Stumpf said there were a number of similar stories, which left her with the conviction that the Holy Spirit was at work in the whole process.

“I really felt the Holy Spirit put these things in the homes where they belonged. And that is a very comforting feeling.”

Most of the items went to churches, Stumpf said, although some were purchased by private individuals.

One Catholic church that is currently under construction in North Carolina purchased the pews from one chapel at the seminary and the altar of repose from another, along with holy water fonts and a statue of Sts. Peter and Paul from in front of the building.

In advertising the art sale, the seminary reached out heavily to alumni – priests in different parishes and ministries across the archdiocese and beyond.

“I think if I were to do this again…there would've been a lot more advertising to the general public,” Stumpf said.

Some items – such as altars, pews, and religious artifacts – could not be sold to just anyone, she conceded. But there were also pieces of art that might have held a broader appeal among the general public.

The buyers were responsible for moving the items they purchased. However, Stumpf said the seminary was able to give recommendations of movers for some of the large and fragile items.

Most of the artwork has been sold at this point. There are still some remaining items, including non-religious furniture, which will be auctioned, Stumpf said.

And some pieces ended up in other homes, without ever being put up for sale. Some items were given to the Archdiocese of Philadelphia archives, because they had historical significance for the archdiocese more broadly, Stumpf said.

Those included chalices which had been used during papal visits, cathedra for various bishops, gifts from papal nuncios, and even a pair of Pope Pius X’s shoes.

There was also a historical cross created for John Paul II’s 1979 visit to the archdiocese, which was given to a local retreat center.

Stumpf said she appreciated the care and attention put into the entire process of transferring and relocating the artwork from the original campus. Particularly in today’s disposable culture, she said, it was encouraging to see the acknowledgement that the art not only had value, but was part of a tradition that was worth continuing.

Stumpf said she recently spent time in the chapel at the new seminary, where she was struck by the beauty of the stained-glass windows, which had been brought in from the old campus.

While the windows were always beautiful, the building configuration and the interplay of light and shadows in the new chapel made them particularly striking.

“I was just overwhelmed with how magnificent those windows were,” she said. “They never looked that spectacular in their home of 150 years.”

Making home away from ‘home’

With the new semester well underway, the men studying at St. Charles Borromeo are adjusting to their new home.

Once the new campus was ready, the seminary held dedication ceremonies for the college seminary chapel and the theology chapel.

(Before the move, Chylinski explained, he had to write to the archdiocesan chancery to receive a relegation of the old chapel, decreeing that it was no longer being used for sacred purposes.)

The new location, situated on the edge of a bustling college campus, is different, Chylinski acknowledged. But tucked away on the very northern edge of the campus, it still feels distinct.

“We have our own space,” the bishop said, adding that the seminarians are free to use some of the university’s athletic spaces, and there will likely be opportunities to invite university students to the seminary’s liturgical devotions and other special events.

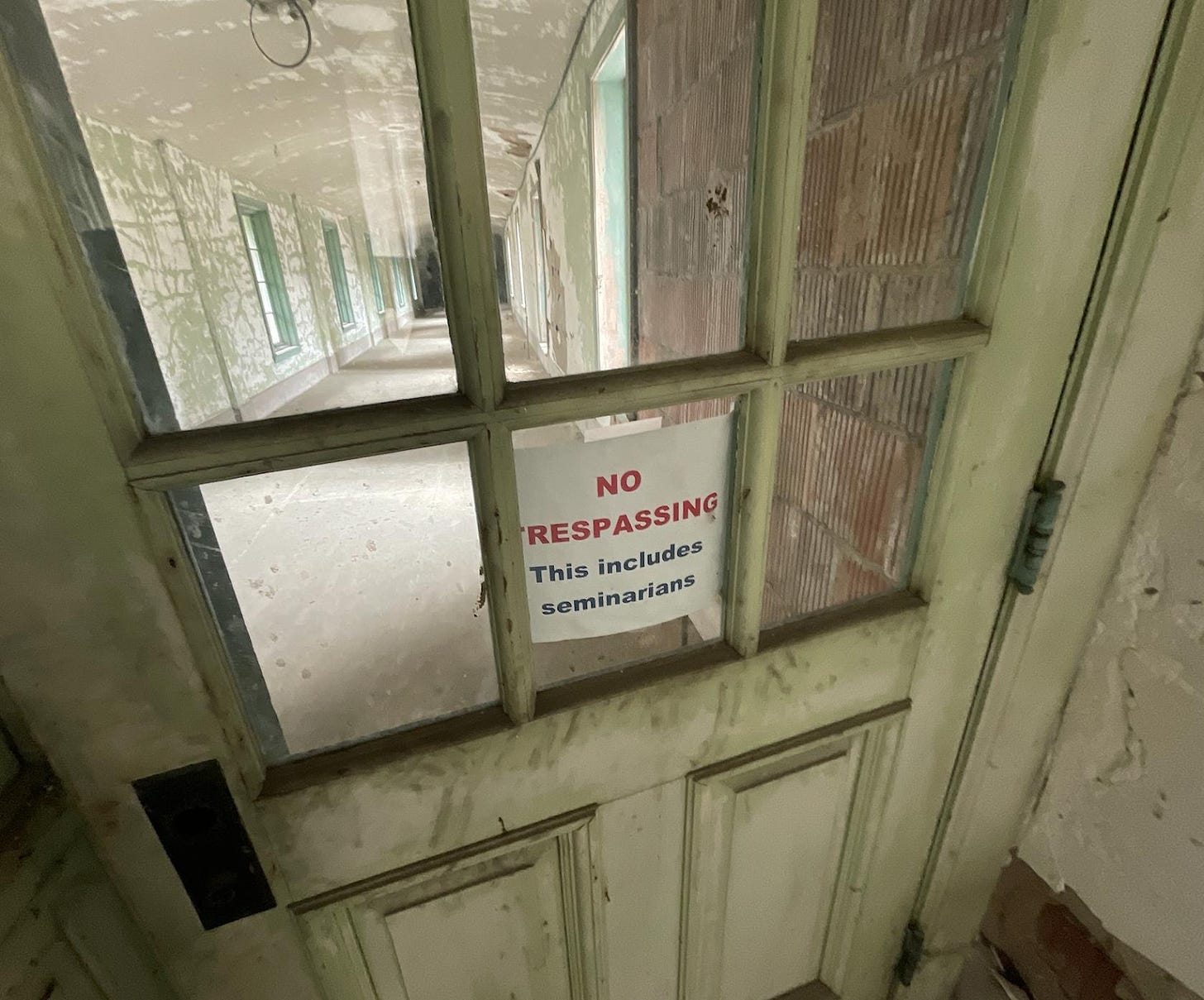

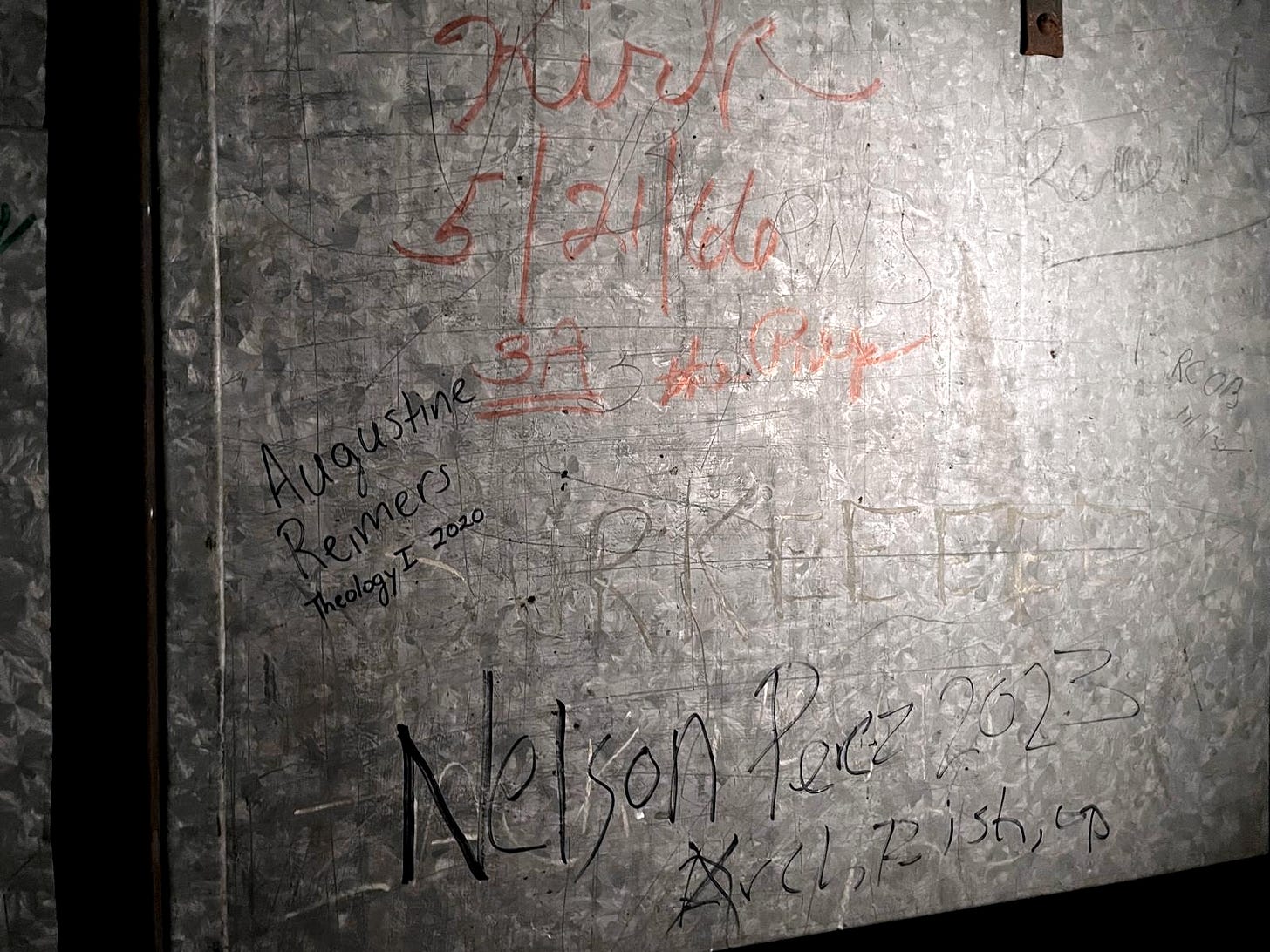

Still, adjusting to a new location is always a transition – especially for an institution that has spent well over a century at its prior location — a location rife with history, its own lore, and even a well-loved tunnel between buildings.

Chylinski said that while the archdiocese was convinced that the seminary move was the right decision, it was still a difficult one. There was a 150-year history attached to the old campus, and some people felt upset about the move, even though they understood that the difficult financial situation made it necessary.

“I've really been very conscious of trying to acknowledge people's grieving. It truly has been a grieving process, I think, for many, including myself, to leave the campus. So I think to just acknowledge the truth of that, acknowledge the reality of the sadness of leaving – that was a very high priority of mine,” he reflected.

Chylinski acknowledged that the community is still undergoing an adjustment period.

“I think certainly bringing a lot of our revered items from the old place helps it to feel very familiar,” he reflected. “And especially in our chapels, we have a lot of the stained glass, the marble statues, the altar all came from the old campus, the pews as well.”

Interestingly, the bishop said, when the seminarians were asked how they felt after moving into the new buildings, they almost immediately began to say that they felt at home.

“I think we feel at home wherever God has us. Certainly the objects and the items that we brought with us that are familiar help. But in the end, wherever God plants us, he's there and wherever he is, we're truly home. And I think the guys are already experiencing that.”

In an article published on the seminary website, one seminarian reflected, “It’ll be interesting to see what our old traditions look like at the new place.”

Chylinski said some of the seminary’s traditions – like the flag football game on the patronal feast of St. Charles Borromeo – will be easy to replicate on the new campus.

Others may be logistically challenging. For example, there is a longstanding tradition that after deacons finish their final classes and prepare to leave the seminary to be ordained, a special ceremony is held following Vespers. The other seminarians ring the chapel bell and stand on either side of the aisle, clapping for the deacons and wishing God’s blessings on them as they leave.

“They clap them out of the seminary,” Chylinski said.

“We took that very same bell and the same rope too for our new bell tower, but the configuration is different. So I'm curious to see how we're going to continue that clap-out tradition for the newly ordained in the new space.”

Over time, the bishop noted, new traditions are likely to develop in the new space as well.

“[We’ll] just see what other traditions might also evolve.”