How the Jesuits could have laicized Rupnik, and why they should have

Is Marko Rupnik still a cleric because of a lack of legal leeway for the Jesuits, or a lack of will?

The Society of Jesus on Monday released a letter on the case of Fr. Marko Rupnik, the disgraced religious artist and priest who was expelled from the order earlier this year, after dozens of accusations of sexual abuse of religious sisters came to light against him.

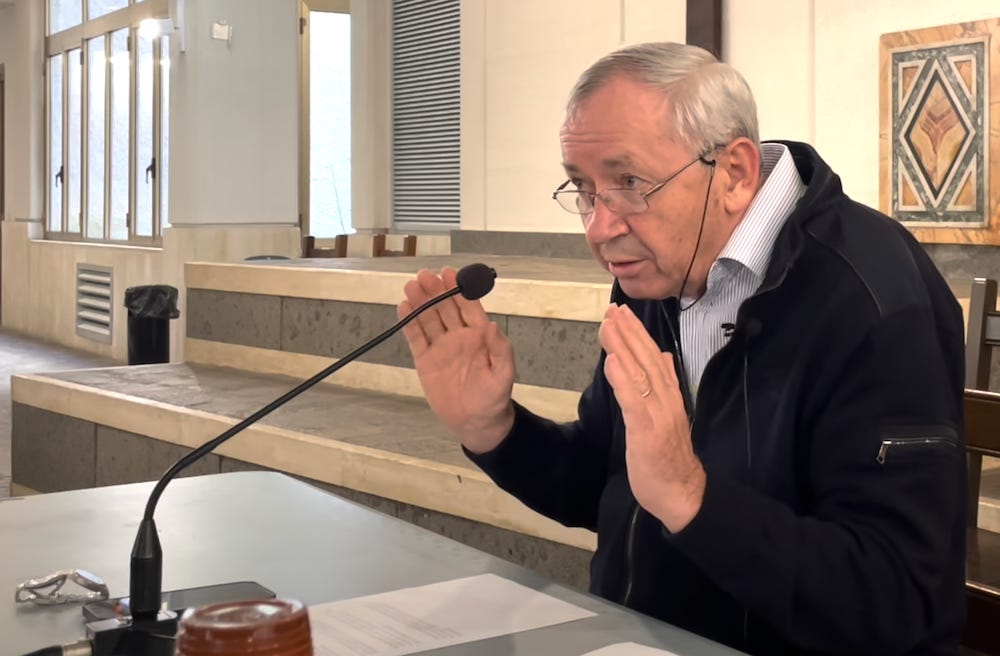

The letter, signed by Fr. Johan Verschueren, S.J., the Jesuits’ superior …