How Sudan’s Catholics are surviving the war

When civil war broke out two years ago, there were more than 1.2 million Catholics in the country

When civil war broke out in Sudan two years ago today, there were more than 1.2 million Catholics in the country.

Although 90% of the nation’s roughly 50 million-strong population is Muslim, Sudan has had a significant Catholic presence for almost 200 years. Africa’s third-largest country is linked with saints such as Josephine Bakhita and Daniele Comboni, and other holy figures such as Zeinab Alif, a slave who became an abbess.

Before fighting upended everyday life, Catholics worshiped in prominent buildings such as St. Matthew’s Cathedral in the capital, Khartoum, and Our Lady Queen of Africa Cathedral in El-Obeid.

In 2023, the year the war erupted, the Khartoum archdiocese, which covers the northeastern half of the country, had 79 priests, 123 religious, and 4 permanent deacons, serving a steadily growing Catholic community in 17 parishes.

What’s happened to Sudan’s Catholics in the past two years? It’s hard to build a comprehensive picture because of the fog of war. Reports have been patchy, but they give us some insight into the conflict’s impact on the country’s Catholic minority.

Here’s what we know.

Bombs and beatings

Sudan has been in a near-constant state of civil war since it gained independence from Britain and Egypt in 1956. Over the past 70 years, it has seen as many as 20 attempted military coups, an undesirable record in Africa.

The latest conflict began on April 15, 2023, but has its roots in a coup in 2019 that overthrew the country’s strongman president Omar al-Bashir. The coup was executed by the Sudanese Armed Forces, the national military forces, which took control of the country with the help of a paramilitary group called the Rapid Support Forces.

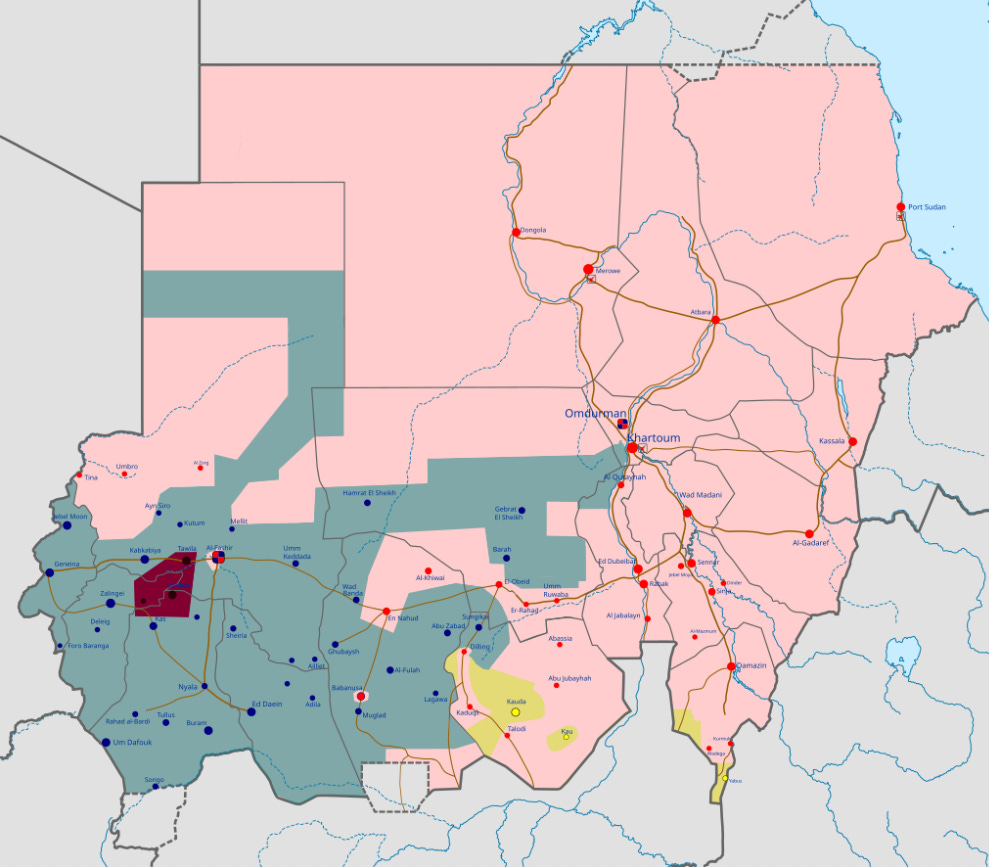

In 2023, RSF attacked SAF bases, in an attempt to establish its dominance. But the RSF lacked the resources to conquer Sudan’s vast territory, leading to a bloody, intractable war that has killed tens of thousands of people and displaced more than 13 million others.

Weeks after the civil war started, the cathedral of the Diocese of El Obeid, which covers the southwestern half of Sudan, was hit by at least two rockets while the bishop and priests were praying before the Blessed Sacrament. They escaped unharmed.

In November 2023, shells struck the Mariam Home, a building belonging to the Comboni order in Khartoum’s Al-Shajjara neighborhood, reportedly injuring five nuns and several children.

By February 2024, nearly a year into the conflict, the toll on the Church was evident. Vatican News quoted an anonymous missionary saying that Khartoum, the focus of some of the heaviest fighting, now only had four priests and four nuns. The missionary said other priests had been forced to flee the capital, seeking refuge in less war-torn cities.

Khartoum’s Catholics continued to “gather on Sundays to pray together with the catechists, despite there being constant carpet bombings which make travel very difficult,” the missionary said, noting the absence of the Eucharist and other sacraments.

Catholics, along with the rest of the population, faced not only insecurity and spiritual deprivation, but also a daily struggle for limited supplies of food, water, and electricity, in what is frequently described as the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.

By the war’s first anniversary, an estimated 165 Christian churches had been forced to close. Many Catholics who were able to flee had crossed the border to South Sudan, a country with a larger Catholic population but also prone to instability.

In August 2024, there was a moment of relief for one Catholic community in Khartoum when the SAF evacuated five Italian nuns, a Salesian priest, and 20 South Sudanese nationals from a residence in the capital, where they had been stranded for over a year.

In December 2024, El Obeid’s Bishop Yunan Tombe reported that he and a deacon had “missed narrowly martyrdom” when they were accosted by members of the RSF.

The bishop said the paramilitaries had inflicted “countless heavy blows on the neck, forehead, on my face, and two sides of my head,” leaving him unable to move his jaw to eat food.

A resilient Church

This is a far from exhaustive account of the Church’s troubles during two years of civil war in Sudan.

But alongside great hardships, local Catholics report signs of hope. Not long after he was assaulted by the RSF, El Obeid’s Bishop Tombe said that vocations remained strong in his diocese.

“We currently have more than 70 youngsters in our formation houses, and I will be ordaining six new young priests this year,” he said in January.

But the plight of the bishop and his flock remains dire. His rectory has had no running water, electricity, or internet since 2023, and only a sporadic phone connection.

He noted that people seeking help from the Church were “pale because of hunger,” but found solace in God’s presence.

“During this difficult situation, faith is stronger, and even more sacraments are being administered,” he said. “More people are coming to the Church, there is more need for the priests, and for the bishop.”

Over the past two years, the Sudan/South Sudan Catholic Bishops’ Conference has called insistently for peace. Pope Francis has echoed its appeals, most recently in his April 13 Angelus address, in which he marked “the second sad anniversary of the beginning of the conflict.”

But the combatants have ignored the bishops’ entreaties. The SAF has retaken Khartoum and other territories, and believes it has the momentum for victory. The RSF, meanwhile, is determined not to be dislodged from its pocket in the southwest.

External players are content to continue offering support: Iran, China, and Russia to the SAF; the UAE and Libyan groups to the RSF. Other wars, in Gaza and Ukraine, command the attention of world leaders.

While many Catholics in Sudan have left their homes, others have nowhere else to go. As long as they remain, the country’s bishops, priests, and nuns will live alongside them, doing their best to serve them with limited resources.

When the civil war finally ends, the Catholic Church in Sudan is likely to be significantly smaller. But it may, paradoxically, have even more spiritual vitality than it did before.

If all these articles are the result of you taking a vacation, you should take them more often. Thank you for shedding some light on the situationn

Lord have mercy on us. Have mercy on the people of Sudan.