Hong Kong bill threatens confessional seal, warn advocates

Human rights advocates are warning that a new national security law poses “profound and grave concerns" about religious freedom

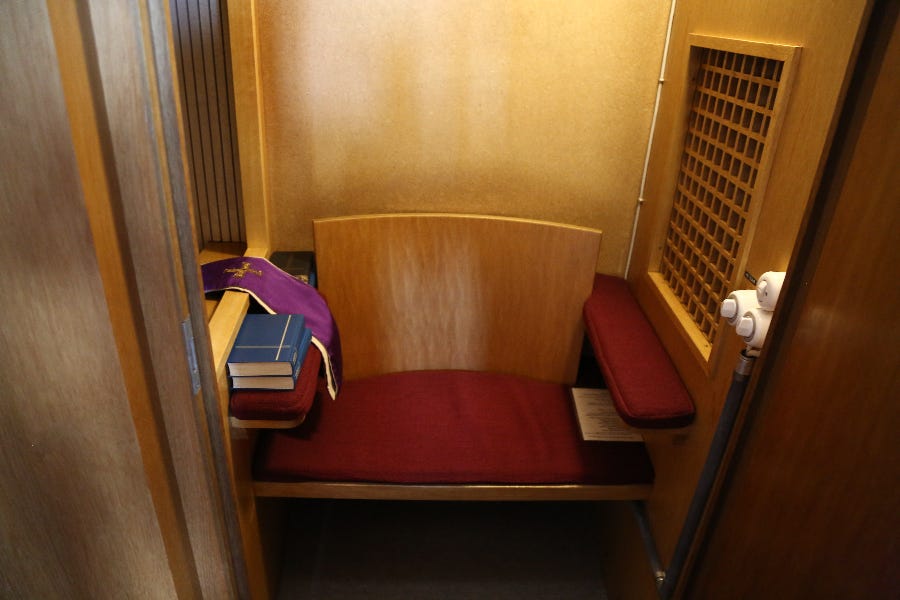

Catholic priests could face pressure to violate the sacramental seal of confession if a new security bill becomes law in Hong Kong, human rights advocates said Wednesday.

A group of 13 activists and three organizations signed a March 13 statement expressing “profound and grave concerns …