Is there a 'McCarrick effect' for diocesan appeals? A look at trends in diocesan giving

A Pillar special report

Diocesan-wide fundraising appeals have declined in recent years, a study conducted by The Pillar concludes.

But the decline is not consistent across dioceses, and some local Churches have seen appeals grow in recent years, even with the Church in the U.S. battered over the last three years both by news that one of its most prominent cardinals was a sexual abuser and by increasing division over doctrinal and political issues.

A special report from The Pillar looks at trends in diocesan annual appeals, and asks what they might signify for the Church’s ongoing fiscal health.

After the the 2018 scandals of Theodore McCarrick and the Pennsylvania grand jury report on clerical sexual abuse, some Catholics began to say publicly they would no longer support diocesan appeals. Those voices grew louder amid discontent over the Church’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic. But are frustrated Catholics actually scaling back their financial support for their dioceses? We went to the numbers to find out.

The Pillar examined records of annual appeal collections in 25 geographically and demographically diverse dioceses from 2016 to 2020. We found that on average, the collections of diocesan annual appeals have gone down 4% during the last 4-5 years.

(Some dioceses in our sample set have not yet posted their audited 2020 financials, and others included 2020 but only published financials back to 2017. We did not include any dioceses with fewer than four years of published financials in our study.)

Prominent urban dioceses and archdioceses have seen more dramatic declines in appeal revenue than other parts of the Church in the United States.

The six U.S. archdioceses currently led by cardinals saw an average decrease of 9% in their annual appeals between 2016 and 2020, while dioceses without cardinals were, on average, down 2% during the same period.

Keystone declines?

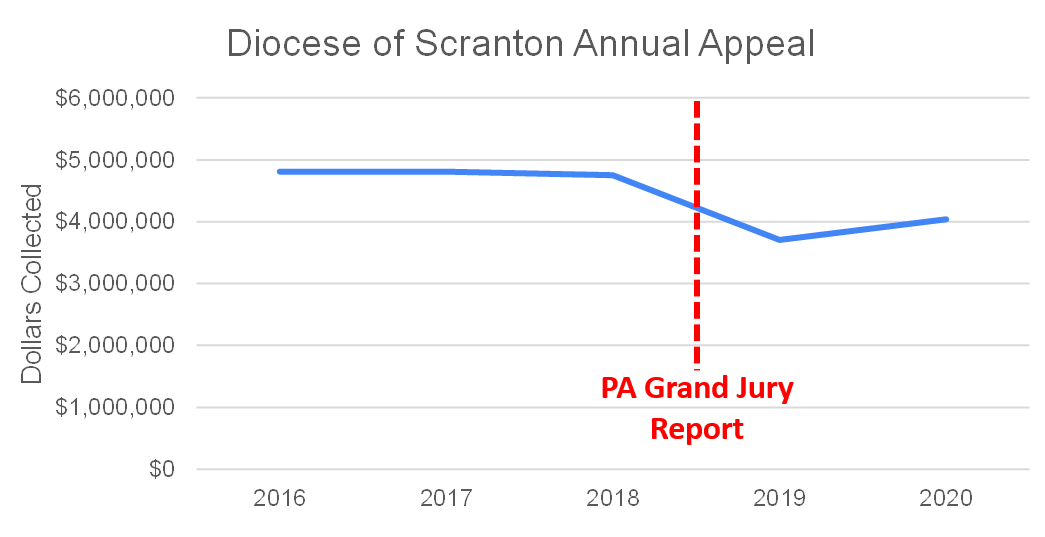

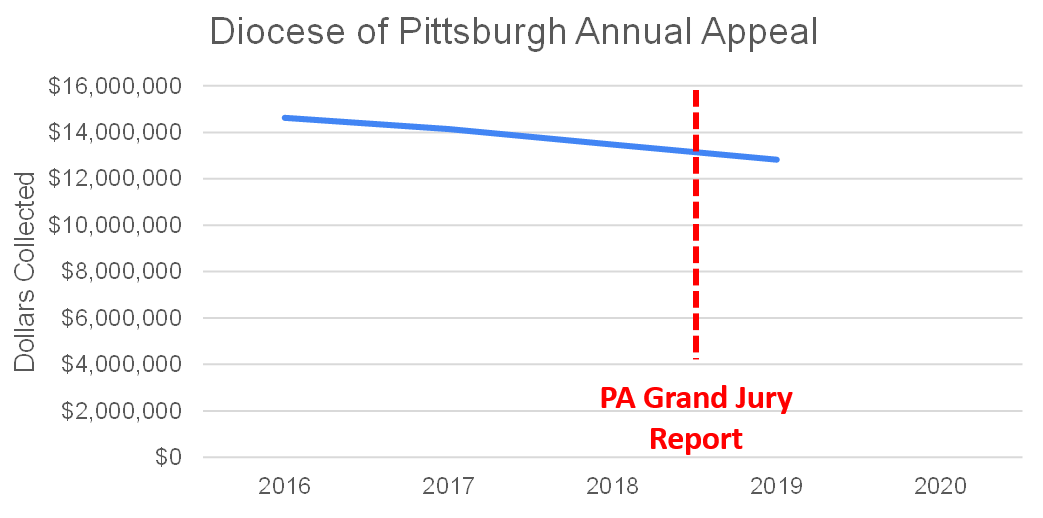

Three dioceses in Pennsylvania - Pittsburgh, Scranton, and Greensburg - were included in our data set. On average, those three dioceses saw a decrease of 8% in their annual appeals. It is possible that decline was impacted by the spotlight put on Pennsylvania dioceses after the August 2018 publication of a state grand jury report on sexual abuse in the Pennsylvania.

Scranton and Pittsburgh both saw their lowest annual appeal collections during the year after the report’s publication, while Greensburg, where the annual Lenten Appeal has remained stable in recent years, did not seem to be affected.

Data available from other Pennsylvania dioceses was not sufficient to confirm the possibility of a grand jury related trend. The Diocese of Harrisburg has suspended publication of its audited financial statements until its ongoing bankruptcy process concludes. The Archdiocese of Philadelphia does not conduct a diocesan appeal, although it does have a Catholic Charities Appeal administered by an entity legally and operationally independent from the archdiocese, and data from the Diocese of Altoona-Johnstown was not readily available online.

New Jersey on the rise

The Archdiocese of Newark had a surprisingly positive trend among dioceses led by cardinals, with the 2020 annual appeal collecting 19% more than the 2016 appeal did.

Newark was the only diocese led by a cardinal which saw an increase in collections between 2016 and 2020, which might come as a surprise given the archdiocese’s association with disgraced former cardinal Theodore McCarrick.

It is possible that Newark’s apparent fundraising increase was really the result of a relatively low starting point. Even with its improvement from 2016 to 2020, the average appeal collection amount in the Newark archdiocese over five year was only $3.49 per Catholic, the lowest of amount per Catholic of any diocese that we examined.

The Diocese of Metuchen, NJ, where McCarrick served as diocesan bishop from 1982 to 1986, also saw an increase in its annual appeal over the four years from 2016 to 2019.

Results may vary

The Archdiocese of Boston declined the most among dioceses led by cardinals between 2016 and 2020, with a decrease of 26% in the period.

Boston was closely followed by Washington D.C., McCarrick’s final see, which saw a decrease of 23%.

Other dioceses whose bishops are prominent in the news had varying results.

Tyler, Texas - led by oft-tweeting Bishop Joseph Strickland - saw a 16% decrease in its annual appeal between 2016 and 2019, the last year for which date was available.

Archbishop Samuel Aquila of Denver and Cardinal Blase Cupich of Chicago, who recently clashed in essays over the issue of Eucharistic coherence, both saw a 3% decrease in appeal collections between 2016 and 2019.

And the Diocese of Knoxville, Tenn., led by Bishop Richard Stika - whose likely investigation under Vox estis lux mundi has been covered by The Pillar - saw an 18% increase in annual appeal collections from 2017 to 2020. In fact, Knoxville saw the highest amount of appeal collections per Catholic of any of the dioceses in our study.

The pandemic that keeps on giving

When we at The Pillar began our study, we did not expect to find that the COVID-19 pandemic would be a significant factor in 2020 diocesan appeals. Dioceses in the United States usually run on a July to June fiscal year, which means the 2020 fiscal year ended on June 30th, 2020. As a result, only three months of the 2020 fiscal year would have been affected by the pandemic.

But it turned out that a number of dioceses were significantly affected. Most dramatically impacted was the Archdiocese of Detroit.

Between 2016 and 2019, Detroit’s annual appeal collections increased 1%. But in 2020, collections dropped by 47%.

The archdiocese explained in its annual report, that the annual appeal was scheduled to begin in March 2020. With the onset of the pandemic, the archdiocese decided to delay the collection until later in the year, hoping to be able to conduct it in better conditions. But as the pandemic continued the decision was eventually made to move forward with the collection in September, and collections were diminished significantly.

Los Angeles was another archdiocese significantly affected by the pandemic. Through 2019, the archdiocesan annual appeal had increased by 9% from 2016. In 2020, however, collections were 10% below their 2016 level.

Unlike those dioceses, most dioceses we studied did not seem to see a significant pandemic effect in their 2020 diocesan appeal. But it seems reasonable to project that appeal number in their 2021 reports will reflect a downturn.

The big picture

If you’re like most Catholics, and you haven’t sat down to read 125 diocesan audited financial reports, you might not know the details of where a diocese’s money actually comes from and where it goes.

Here’s a quick explainer on the dollars that make a diocese function:

Most dioceses get 80% to 90% of their revenues from three sources:

Annual fundraising appeals of the sort we examined in this study

A tax (called an “assessment”) which dioceses levy on parishes, by which parishes pass on a set percentage of their weekly collections to the diocese

Other contributions and bequests

The other 10% to 20% of diocesan revenue comes from investment income, rent on properties owned by the diocese, and other sources. (In this assessment, we have not included “pass through” funds, such as when a diocese manages health benefits for all employees of Catholic parishes and schools in the diocese. Such arrangements can result in large amounts of premiums collected by the diocese from parishes and schools which are directly offset by large insurance expenses.)

Although dioceses consistently get 80% to 90% of their funds from those three sources, the breakdown between those sources varies widely. For some dioceses we looked at, the annual appeal made up as little as 25% of yearly diocesan revenues, for others it was nearly 50%.

We also looked at several of the dioceses which do not have annual appeals. The Archdiocese of Philadelphia, which does not have an annual appeal, gets 62% of its funds (not counting insurance premiums) from parish assessments, with the rest coming from direct contributions, interest income, and fees for services the diocese provides. The Diocese of Wichita, Kansas, likewise does not have an annual appeal, but gets 100% of its operating funds from parish assessments.

Catholic dioceses are large organizations with annual operating budgets that often run into the tens of millions of dollars. But that amount of money is actually modest compared to the number of people to whom a diocese ministers. We compared the total operating budgets of several dioceses in our study to the number of Catholics in the diocese - according to catholic-hierarchy.org - and found that the average U.S. diocese has an operating budget equal to $55 per year for each Catholic in its borders.

That money goes to support the pastoral programs which are managed at the diocesan level: seminary expenses for new priests, catechetical training and program design, marriage preparation, the diocesan tribunal, campus and hospital ministries, etc. It also goes to support administrative costs, some for the diocese itself and others which support parishes and schools in the diocese. The diocesan legal, accounting, human resources, and information technology departments often provide parishes and schools with services, guidelines, and templates, since individual parishes and schools often are not large enough to employ experienced staff in all of those areas.

Just as dioceses are able to provide specialized services such as IT and legal support more efficiently than parishes could on their own, larger dioceses seem to be more efficient than smaller ones in terms of administrative costs.

When we examined the total expenses for a subset of the dioceses in our study and compared them to the number of Catholics in the diocese, we found that larger dioceses spent less per Catholic within the diocese than smaller ones. This is also reflected in the amounts that dioceses raise through their annual appeals. Los Angeles, the largest archdiocese in the United States, with over four million Catholics, raised an average of $3.60 per Catholic in the archdiocese through its annual appeal. The two smallest dioceses in our study, Knoxville, Tenn., and Tyler, Texas, each with about 50,000 Catholics, raised an average of $46.65 per Catholic in their annual appeals.

The relationship between diocesan Catholic population and the amount of money raised (and thus amount of money spent) per Catholic is fairly strong. In the chart below, we used a logarithmic scale for diocesan population in order to make it easier to see how the relationship persists among smaller dioceses.

It has been nearly three years since news of the McCarrick scandal rocked the Church. But questions of sexual abuse and mishandling of cases in the Church are still being raised. And with the topic of Eucharistic coherence expected to feature prominently at the summer meeting of the U.S. bishops’ conference later this month, the optics of internal division among the hierarchy are likely to be prominent. As Church leaders continue to navigate these challenges, they will also need to face the effect that these phenomena have had on the ability and willingness of laypeople to donate, and the implications of those decisions for their dioceses.