Happy Friday, friends,

Before we get started: JD and I will be in Baltimore for the USCCB meeting next week and hosting a live taping of The Pillar Podcast at Todd Conner’s bar, Wednesday, Nov. 15, starting at 7 p.m — brought to you by the University of Dallas.

If you are in the neighborhood, or just east of the Mississippi, I hope you’ll be there, too.

We had a great time last year, spending the evening with friends and readers from all over.

These live shows are really just an excuse for JD and me to get to spend time with the people who make this all happen — you guys. We look forward to it every year.

See you there.

Moving on: A very happy feast of Pope St. Leo the Great.

As popes go, Leo was pretty great, in terms of his historical significance.

He ended the Christological controversies of his time, and he came up with the formulation of Christ’s nature as truly God and truly man.

That would be enough to cement most popes’ place in the history books.

But with Leo, you can add that he personally convinced Attila the Hun not to sack the Eternal City, and coined the use of “pope” to refer exclusively to the Bishop of Rome. That still covers only a part of what he achieved, actually.

Leo was, by anyone’s measure, worthy of being described as “great.” But what I love about that descriptor is it’s a title not accorded by any canonical process or curial endorsement. It comes only from the common and constant acclamation of the people of God.

I tend to think that’s important because while we — the great unwashed, I guess — might respect great theology and value subtle ecclesiastical diplomacy, it is personal holiness and manifest selfless love in our leaders we tend to acclaim first and most loudly.

And we hoi polloi tend to take a balanced view over time.

Consider St. John Paul II: Shortly after his death, there was a real movement to acclaim him as a “great” — some schools and parishes named for him gave him that title, and even Benedict XVI referred to his predecessor as “the great” on occasion.

There is still a sizable group of Catholics who would consider John Paul II “great,” but the general acclaim isn’t there.

It hasn’t happened yet, and it seems to me that enthusiasm for giving him the title has diminished, not grown, with time.

I think, in large part, this is because, as we’ve learned more about figures from the JPII era like Maciel and McCarrick, we have begun to make a more clear-eyed assessment of his pontificate, its successes alongside its flaws and blindspots.

At the time of his death, I pointedly started referring to him as “John Paul the Great” to do my bit for the cause, as did others I know.

But none of us do that very much now, nearly 20 years later.

Don’t get me wrong, I believe John Paul II to be a saint.

I owe my faith, in large part, to his zeal and support for the new evangelization. He’s the pope who left an indelible mark on the Church and the world I grew up in.

I am, as much as anyone can be, a “JPII Catholic.”

But I can consider JPII to be a holy saint, a great mind, a global statesman, a fierce evangelizer, and, above all, a priest who convinced me that I am loved, and yet still demur about the title “the great.”

I think that’s important. It’s important to see our heroes clearly, with the benefit of hindsight — though it would be better if we could do it in real time.

I wonder, sometimes, if John Paul II could have been truly great if his fiercest admirers had been better able to make him confront his blindspots, and challenge his bad assumptions. I wonder what kind of a Church we’d have today if they had.

Who can say — we’ve got the history that we’ve got.

Here’s the news.

The News

Next week, the U.S. bishops will be in Baltimore for their autumn plenary assembly. As usual, they have a lot to discuss, some of it quite interesting.

The text contains a reference to abortion as “a preeminent concern” — a phrase probably drafted carefully to be a elegant compromise, but just as likely to annoy both wings of the conference hall, with some bishops arguing that “preeminent” is too strong a word, and others insisting that abortion should be framed as the top priority not just a preeminent concern.

Nobody reads the conference better than JD, and this is an important window into what we’re likely to see and hear in Baltimore next week.

—

Also on the docket next week in Baltimore, the bishops will discuss three possible models for the instituted ministry of catechist in U.S. dioceses, which Pope Francis called for in 2021.

Of the three models, one is focused on teaching teachers, another on engagement in secular culture, and a third focuses on institutional collaboration with bishops, according to a Nov. 6 USCCB memo obtained by The Pillar.

The great challenge for the bishops, it seems to me, is this: Can they incorporate the ministry of catechist in diocesan life in a way that actually focuses on evangelizing those outside of the Church?

Or will the whole notion devolve into just another expensive program to create and affirm a professional class of laity as a counterbalance to criticisms of “clericalism.”

We’ll be there in Baltimore to see what happens. Get up to speed here.

Incidentally, you can only read both these stories, and several more to come ahead of Baltimore, here at The Pillar.

Cultivating credible sources, earning and keeping their trust, and reporting what we find out responsibly and with real independence is what we’re all about here. It isn’t easy, and it doesn’t happen overnight.

Keeping this show on the road isn’t easy either. We rely on a fraction of our readers deciding that the work we’re trying to do is worth doing, and worth supporting.

How we go about our work, putting hard news and serious analysis ahead of opinion, is a choice. Paying for the journalism you read is a choice, too. We think the work we’re doing is worth $1.80 a week. I hope you agree.

—

Last week, Cardinal Christophe Pierre said in an interview that he had been “shocked” at how few American bishops knew anything about Aparecida, the 2007 conference and document by Latin American bishops.

According to the nuncio, Aparecida is where to look if you want to understand the importance and effectiveness of the synodal style of leadership which is all that bishops are allowed to talk about these days.

But if Aparecida is, as Cardinal Pierre says, the model for the U.S. bishops to follow in addressing declining rates of faith in their country, it seems reasonable to ask if it worked.

—

On Wednesday, the Vatican’s doctrinal office responded to questions concerning the role of people who identify as LGBT at Catholic baptisms and weddings.

The text, signed by Pope Francis and the DDF’s new prefect, Cardinal Víctor Manuel Fernández, responded to questions from a diocesan bishop about self-described “transgender” persons and the sacrament of baptism, as well as if and when gay people in a stable relationship could serve in different roles, like that of godparent.

The answers were, in large part, just reiterations of previous doctrinal and pastoral guidance offered by the DDF and other Vatican departments, but, interestingly, the Vatican chose to issue the responses publicly right now. ‘

As we’ve reported last year, the DDF has been a little shy about publishing its own full document on these same issues.

—

At the end of last month, Pope Francis named Bishop Víctor Hugo Basabe as the new Archbishop of Coro, Venezuela. The appointment didn’t make international headlines, but maybe it should have.

Since 2017, he’s been the bishop of a relatively small diocese, but since 2020 he’s also been apostolic administrator of Barquisimeto, the fourth-largest archdiocese in the country.

It was widely understood that Basabe was stuck in the administrator role, instead of becoming archbishop proper, because the Holy See’s concordat with the Venezuelan government gives President Nicolás Maduro an effective veto on episcopal appointments.

Since arriving in Barquisimeto, Basabe has emerged as a leading public critic of the regime.

Is his move to become archbishop of a much smaller archdiocese a victory for the Maduro government, a compromise by the Vatican, or actually something else altogether?

Edgar breaks down the possibilities, and they are all frankly fascinating.

At the heart of a University of Dallas education is our unique, semester-long Rome experience. By witnessing the significant sights where Western civilization first flourished and where Catholic intellectual and spiritual traditions continue to flourish today, UD students are immersed in a quest to a life well-lived intellectually, socially and spiritually. Find out more at udallas.edu/pillar.

Progressive decline

This week, Catholic University’s Catholic Project published a new report from its National Study of Catholic Priests, and it makes for very interesting reading indeed.

In the words of the report, “Simply put, the portion of new priests who see themselves as politically ‘liberal’ or theologically ‘progressive’ has been steadily declining since the Second Vatican Council and has now all but vanished.”

In light of the Catholic U report’s findings, I was talking with a friend this week about how bishops would read and respond to the numbers.

You would expect, my friend said, that it would provoke a lot of reflection, especially among the sizable number of bishops who would think of themselves as liberal in outlook. Where have all their vocations gone?

Will they take this as a prompt to recalibrate their seminary recruitment, and the way they foster and encourage young men to consider the priesthood? I’m not so sure.

Of course, we want priestly vocations. All priestly vocations. Whatever your ecclesiological worldview, I hope we’d all agree that if the Lord is calling a man to serve Him in that way he’ll respond generously — whatever wing of the Church he identifies with.

But I wonder if the broader discourse in the Church hasn’t worked to convince many young men on the “progressive” side of the conversation that the priesthood just isn’t a worthwhile vocation.

And I wonder how many liberal bishops will look at these numbers and conclude the problem isn’t with their vocational recruitment, but with the very idea and nature of the priesthood itself.

That seems to be the lesson coming out of Germany, where the most progressive bishops have taken empty seminaries as proof that the very nature of the sacramental priesthood needs to change, not their approach to fostering vocations.

For myself, I don’t think that pushing for women’s ordination, or ending clerical celibacy, or harping on endlessly about clericalism, is going to attract many men to the priesthood — it seems more likely to reinforce the impression that it isn’t a vocation worth pursuing in the first place, which I think has already caused a now visible death-spiral of “liberal” vocations.

Again, that’s a shame. Every vocation to the priesthood comes from God, and the Church needs good and holy men to offer themselves for the service of the Church.

Convincing them to honor that vocation, though, means bishops have to convince them it’s a vocation to a ministry they understand and value.

You can read all about the Catholic U report here.

Every second counts

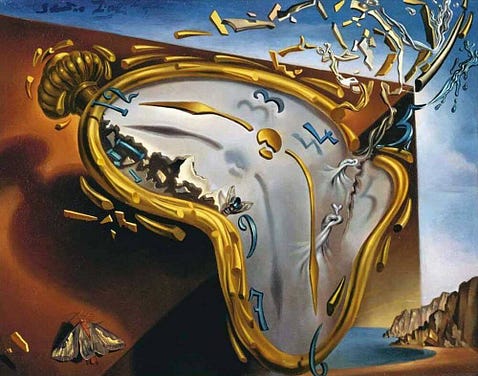

Last weekend, we set the clocks back.

For a lot of people, this is a mundane reality, a meager bonus hour on a Sunday morning offset by the reverse in the spring. For me, though, it’s a moment of celebration, of victory. It’s the time each year that we stop living a lie, if only for a few months.

I say this because, and let’s be absolutely clear, Summer Time, or Daylight Saving Time (DST), or whatever else you want to call it, is absolute nonsense. It’s an act of hubris, a rebellion against the natural order, in which we say as a species: “Yeah, midday isn’t actually for another hour, but let’s hurry this thing up a little.”

I know I’ve written about this before, but time matters — and so does how we keep track of it. It is one of the few absolute things. Who, Christ reminds us after all, can add a single cubit to the span of his life?

Keeping as accurate a track of time as we can is the work of charting our progress through history, marking the ages God has set until the arrival of the day and the hour which only He knows.

Some people, I know, think I am an eccentric for feeling so strongly about this, for being genuinely outraged that we commit an annual mass act of willful denial of reality for our convenience.

But if I am a zealot about these things, I was pleased to learn this week that some people from the Vatican are on my side.

Most people probably don’t care about DST, but they know about it, and about leap years, in which we add a day to the calendar every four years to accommodate the inconvenient truth that the Earth’s solar orbit lasts 365.2422 days. But fewer people know about leap seconds, which happen nearly as often, and often without most people realizing they’re happening.

Ever since the invention of the atomic clock, which keeps absolutely exact time forever, the world has benefited enormously from what we call Coordinated Universal Time — the whole world running from a single clock. That might sound like a luxury, but it’s actually a technical necessity when you are dealing with an interconnected world.

The problem is, the Earth doesn’t keep perfect time. “Observed solar time,” real time you could call it, as opposed to theoretical time, is also now calculated with extreme accuracy. But the problem is that the Earth’s rotation isn’t actually a perfectly regular 24 hours all the time. Geological and climatological (that’s a real word, I checked) factors can slow the Earth’s rotation down sometimes.

Observably but totally unpredictably, the world’s heart sometimes skips a beat, basically.

But, much like we do with leap years, we can’t have theoretical atomic time depart too far from real solar time, or else the whole idea of time becomes arbitrary and meaningless, rooted in abstract conceptions and not the created order.

So, whenever real time and theoretical time get 0.9 seconds out of synch, the world’s timekeepers declare a leap second where the atomic clock is paused for a count of one (1) Mississippi. We’ve done this 27 times since 1972.

It sounds simple, and it used to be, relatively speaking. But it is actually a small technological nightmare in the computer age. There’s no universal timekeeping program used across the digital globe, so making this work takes a number of different fixes in different systems.

You can’t actually freeze digital time for even a second, or systems would crash, so some clocks have to be trained to do a special one-off display of 23:59:60, others have to have a special reverse gear created to make the clock count backward once, for one second, at the stroke of midnight.

Other systems can’t handle anything that dramatic and the second is “smeared” across a whole period of hours until the adjustment is complete.

Every time there is a leap second, we basically face a global mini Y2K panic, and each one is announced six months in advance for people to gear up. Even so, sometimes things go wrong anyway.

Twitter, Amazon, Netflix, and a load of other big brand tech companies bugged out with the leap second in 2015, and several major international exchanges just shut everything down for an hour, just to be on the safe side.

In 2012 and 2017, leap seconds caused New Year’s power outages in New York.

So, man’s convenience being the measure of all things these days, the technocrats at the International Bureau of Weights and Measures have voted to abolish leap seconds by 2035. Instead, they would prefer to let reality slide for however long it takes until we need to do a full leap minute.

For people who care about this sort of thing, it's expected to be a big deal at the next World Radiocommunications Conference, which happens this month.

Almost everybody is on board with the plan. The National Institute of Standards and Technology, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration, the General Conference on Weights and Measures, everyone, it seems, wants rid of leap seconds.

Well, almost everyone. Some of us think every second counts.

According to the New York Times, the Russian government is vigorously opposed to stopping leap seconds and moving to leap minutes.

While their reasons are apparently as mysterious as their objections are forceful, the most likely explanation is that the Russians’ satellite network is geared up for leap seconds, and making a change to leap minutes would be beyond their capacity to accommodate.

We should probably add that to the arguments in favor doing it, I guess.

The British government is totally against the plan too, it seems. Reasonably so, given that before Coordinated Universal Time, the world set its watches by Greenwich Mean Time, calculated by solar observations averaged across the whole year — which is a really good way of keeping real time.

But another voice against this plan for global indifference to the realities of a created world comes from the Vatican Observatory Research Group in Tucson.

(Yes, the Vatican has an observatory in Arizona. The light pollution in Rome and at Castel Gandolfo is exactly that bad.)

Fr. Paul Gabor, S.J., an astrophysicist there, noted quite rightly that doing away with leap seconds and just letting the world’s clocks slide away from the Earth’s reality for years on end could “create some uneasiness, as humans feel connected to the natural world.”

“Men look to the sky and count days; this is something ‘unspoken’ but deep in the heart of men.”

Amen to that.

Disconnecting ourselves, our time, our measurement of reality from the physical world seems to me to be a Babel-esque bid for existential autonomy. It’s an act of defiance against the natural order that cries to heaven for correction.

You just think about that in March, the next time you put your clock forward.

See you next week, hopefully for the live show at Todd Conner’s bar, Wednesday, Nov. 15, starting at 7 p.m. Be there!

Ed. Condon

Editor

The Pillar

I’m probably one of your more progressive subscribers and speaking strictly for myself and no one else, I’m less concerned about the ideological leanings of young priests as I am their humility and their willingness and ability to be pastoral toward parishioners who don’t share their opinions on things that are not essentials of the faith.

One of the biggest problems caused by the priest shortage in many dioceses, in my opinion, is that young priests are often thrust into roles leading entire parishes when they (and us) would be much better served by them working with older, more experienced priests for a while and getting used to the messiness of dealing with the flawed and often difficult people put into their care.

I’ve never had to supervise young priests but I did run the public defender offices in a three county area before I retired and I hired, supervised, and tried to mentor a bunch of young lawyers. The young lawyers I hired at our PD offices were smart and idealistic and really zealous about the work they were doing. But they usually needed some guidance in moving from theory to practice. They often had to be taught how to deal with others that didn’t share their opinions and they often needed help in resolving the inevitable conflicts of the job in ways that didn’t burn bridges. I probably advised every young lawyer I supervised at least once (and some a lot more than once) of the old maxim that you should never attribute to malice that which is more easily explained by incompetence. I suspect a lot of young priests right out of seminary are a lot like my young lawyers fresh out of law school. They are idealistic and on fire for the faith but they need some mentoring and experience. I think bishops do the young priests an injustice by putting them in positions for which they are not yet ready.

Just thinking out loud that in the modern age I wonder if anyone will be considered "great" again? There is simply so much more information and cynicism and the standards keep changing ... . If St. Pope JPII isn't "great" I don't see much hope for anyone else.