‘Government oversight’ for NY diocese? Not exactly

Some media reports have claimed that the Buffalo diocese has agreed to “submit to government oversight” as part of the settlement.

The Diocese of Buffalo announced a settlement Tuesday in the lawsuit filed by New York’s attorney general, over the diocese’s handling of clerical sexual abuse allegations.

Some media reports have claimed that the Buffalo diocese has agreed to “submit to government oversight” as part of the settlement.

Is that true? What does the settlement actually say?

The Pillar explains.

What’s been going on in Buffalo

The attorney general’s lawsuit was filed against the diocese in 2020, charging a coverup in more than 20 alleged cases of clerical sexual abuse.

The suit came after a protracted public scandal under the tenure of former diocesan bishop Richard Malone, who resigned from office in December of 2019, a year after a former Buffalo chancery employee leaked diocesan documents to local media on the diocese’s handling of claims of clerical sexual abuse.

In the months before to his resignation, Malone said he “personally need[ed] to repent and reform” after widespread reporting on his handling of abuse cases and allegations of covering up some accusations.

In August 2019, a separate RICO lawsuit was filed against the diocese and Malone, alleging that diocesan handling of abuse accusations was comparable to an organized crime syndicate.

The following month, recordings of private conversations appeared to show that Malone believed sexual harassment accusations against a diocesan priest months before he removed the priest from ministry.

On the recordings, Malone can be heard calling the situation a “true crisis. And everyone in the office is convinced this could be the end for me as bishop."

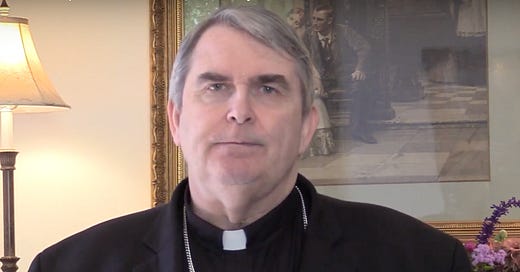

In September 2019, Bishop Nicholas DiMarzio of Brooklyn was appointed by the Vatican to head an apostolic visitation of the diocese, leading to Malone’s resignation in December. Albany’s Bishop Edward Scharfenberger was named temporary administrator of the Buffalo diocese, and filed for bankruptcy. Scharfenberger led the diocese until December 2020, when Washington, DC, auxiliary Bishop Michael Fisher was named the new Bishop of Buffalo.

What did the settlement say?

In a letter announcing the settlement Tuesday, Bishop Michael Fisher said the agreement showed “the Diocese’s utmost commitment to ensuring that all young people and other vulnerable persons are safe and never at risk of abuse of any kind by a member of the clergy.”

For the state’s part, Attorney General Letitia James said the settlement means that “the Buffalo Diocese will now begin a much-needed era of independent oversight and accountability.”

But while the majority of the commitments made by the diocese in the settlement are actually already its policy, the agreement does contain some new provisions.

The Buffalo diocese agreed to create the new post of Child Protection Policy Coordinator, who will also have specific responsibility for overseeing clergy taken out of ministry after an accusation of abuse. On Tuesday, the diocese announced the appointment of Melissa Potzelr, a former district prosecutor and defense attorney, and a parish life coordinator in the diocese, to the role — Potzler is also being appointed a vice chancellor in the diocese.

The court settlement also bars Buffalo’s previous bishops, Malone and former auxiliary Bishop Edward Grosz, from serving as director, trustee, officer, or other “fiduciary” for a charity in the state, though neither is barred from ministry.

Government oversight?

The settlement’s most attention grabbing provision is that the diocese has agreed to an annual independent audit of its handling of abuse allegations and compliance with its own policies for accused clerics.

But while some media outlets have claimed that the audit amounts to the diocese “submitting to sweeping government oversight of its operations,” the reality is much less dramatic.

The diocese contracts already with an external auditor every year to evaluate policy compliance, using StoneBridge Business Partners, the company contracted by the USCCB to audit diocesan compliance with the Dallas Charter, which was adopted by U.S. dioceses in the early 2000s.

📰

According to the settlement, a second independent review is to be conducted by an auditor who is chosen with agreement from the state attorney general and approved by the court handling the diocesan bankruptcy filing.

When the settlement was announced Tuesday, the diocese confirmed that Kathleen McChesney had been appointed to the role.

Under the terms of the settlement, McChesney, a former FBI investigator and the former executive director of the USCCB’s office of child and youth protection, will have “full access to all relevant departments and records and the full cooperation by all diocesan representatives necessary” to conduct her review for the duration of the settlement — set by the court at five years.

In addition to sending her annual report to both the diocese and the Office of the Attorney General, McChesney’s conclusions are expected to be made public each year, as the diocesan independent audits already are.

While the role of a second independent auditor was created under the terms of the settlement, and while McChesney’s appointment had to be confirmed by the attorney general’s office, she does not report to the government, or work for a government agency.

Open questions

Although the Buffalo settlement does not actually entail the diocese submitting to “sweeping government oversight,” the details of the agreement do raise some questions about the independent audit, and about existing diocesan policies related to abuse allegations.

The settlement reports that during attorney general reviews diocesan files - which were conducted under subpoena - state officials had access to “communications to and from the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith,” the Vatican department responsible for receiving and ordering the canonical prosecution of clerical sexual abuse of minors.

The text of the settlement makes clear that the new independent auditor is to be given access to all necessary and relevant documentation related to allegations of clerical abuse, but does not make clear if this pertains to case files of ongoing investigations or canonical prosecutions authorized by the Vatican office.

In his letter to the diocese on Tuesday, Bishop Fisher noted that last June he implemented a new “Priest Supervision Program” to provide policy and oversight of clergy removed from ministry. The same policy was included in the settlement, and compliance with it was placed under the remit of the independent auditor.

The program provides a number of restrictions to be imposed on clergy subject to a “substantiated” allegation of abuse, including a ban from dressing or presenting as a cleric and from serving in public ministry.

The term “substantiated” is not defined in the settlement document. While it is often used by American dioceses to describe accusations, it can variously mean that an accusation has been found to be likely true on the balance of probability, or merely that is not “manifestly false or frivolous,” using a Vatican standard of proof called “semblance of truth.”

The Pillar asked the Diocese of Buffalo to clarify the definition of “substantiated” in the settlement agreement and in its diocesan policy, but did not receive a response.

The supervision program also bans accused clerics from “viewing, downloading, or otherwise possessing pornography,” and from “attending any place that features sexual performance such as a strip club or 'adult bookstores.'”

It is not clear from the policy if this prohibition is only applied to clerics after accusations of abuse, and if diocesan clerics are otherwise not barred from possessing and viewing pornography and attending sex venues under diocesan personnel policy.

Editor's note: This explainer initially indicated that cases pertaining to the clerical sexual abuse of minors are covered by the pontifical secret. That was an error: A 2019 rescript from the Holy See removed the obligation of the pontifical secret in such cases.