Going Dutch? Bishops, university split over Catholic identity

Bishops and a Dutch Catholic university are split over what to do as their country secularizes, fast.

The Vatican informed the Dutch bishops last year that the Church will continue to consider Radboud University in Nijmegen to be a Catholic university, despite the bishops’ decision in 2020 to strip the university of the title “Catholic.”

The Dutch bishops were informed of the Vatican’s decision during their November ad limina visit.

The news is the latest chapter in a controversy over the university which has put bishops and university leaders at odds for more than 15 years, over questions of Catholic identity, bioethics, and members of the board of directors.

But the controversy is not over. And while the situation in the Netherlands has some unique elements, it might also portend the way the Vatican will in the future handle Catholic universities in increasingly secularized Western countries.

📰

The idea of the university?

The standoff at Radboud University can be traced back to the university’s origins — and to the history of the city in which it is located..

The university was founded in 1923, as the Catholic University of Nijmegen, during the “Catholic emancipation” in the Netherlands.

Historically, Catholics faced discrimination in the Netherlands, a majority Protestant country. The majority-Calvinist Dutch Republic forbade Catholicism in the 1580s, and a Catholic episcopal hierarchy was not reestablished in the country until 1853.

In the century that followed, known as the Rijke Roomse Leven, (Rich Roman Life), Catholic life flourished, with Catholic schools, newspapers, hospitals, unions, a political party, and eventually radio and television companies.

The Catholic University of Nijmegen was founded in the middle of that period.

But from the beginning there was disagreement as to its mission: Was the university meant to become a hub for Catholic intellectuals to serve the broader Dutch society, so Catholics could be seen as respectable Dutch citizens? Or was it meant to be a tool for evangelization to non-Catholics? Or could it be both?

“This issue began in 1923, when the university was founded, because the Vatican and the bishops put the emphasis on the missionary aspect of the university, while the board saw the main goal of the university as making Dutch Catholics respectable,” said Christoph Lüthy, a former dean of philosophy, theology, and religious studies at Radboud University.

“So, what the board wanted was educated lawyers, doctors, politicians, engineers, educated bourgeoisie, basically. So the clash between the university and the bishops is a clash of a hundred years, sometimes more virulent, sometimes softer.”

The structure of the university itself also fueled a sense of independence from the ecclesiastical hierarchy.

“The bishops were involved in the founding of the university, but the university itself was not canonically erected. Only the faculty of theology itself was canonically erected, while the university was approved by the Vatican in 1923,” Carl Sterkens, Radboud’s dean of theology, told The Pillar.

Early tensions

The city of Nijmegen has always played a key role in Dutch Catholicism. Doctor of the Church St. Peter Canisius, a key actor in the Catholic Counter-Reformation and the first Dutch Jesuit, was born there in 1521.

St. Titus Brandsma, martyred by the Nazis, was a founding professor of the city’s university and served as rector in 1932-33.

Edward Schillebeeckx, one of the key figures among the more liberal group of theologians that influenced the Second Vatican Council, was a professor of theology at the university from 1958 to 1983.

But the city’s historical identity has had an influence on the university’s identity, some Catholics say.

“Nijmegen is a very self-conscious, politically active city. The university started as a way to emancipate Catholics, so they could, in a way, say ‘no protestant will tell me what to do’, but that sense of emancipation also went against the bishops eventually,” Fr. Joseph Geelen, Radboud University chaplain, told The Pillar.

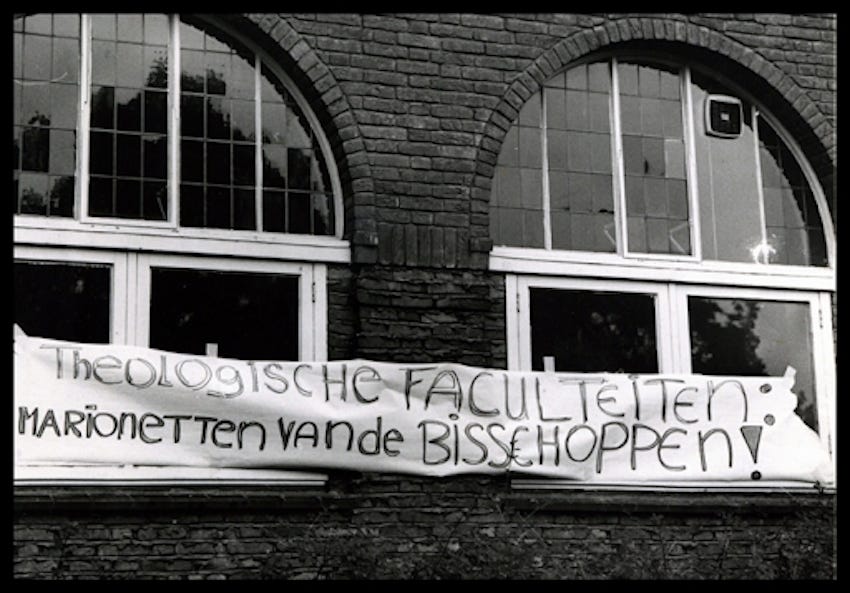

Eventually, the university became the forefront of the growing divide between a generation of more liberal-minded priests and theologians, and a Dutch hierarchy that was increasingly conservative because of episcopal appointments made by Paul VI and John Paul II. As that split grew, tensions between bishops and the university seemed to grow sharper.

Eventually, the strain led to the first formal sanction against the university, in 2005.

Bishop Gerard de Korte of ‘s-Hertogenbosch, the diocese where the university is located, told The Pillar:

“During the ad limina visit in March 2004, Rome asked the Dutch bishops to come to a merger of the theological faculties of Nijmegen, Utrecht, and Tilburg. The background for this question was the declining number of students. The conversations that followed resulted in a merger of Utrecht and Tilburg.”

But the Catholic University of Nijmegen, which changed its name to Radboud University in 2004, stepped away from the negotiating table.

“This disappointed the Dutch bishops at that time,” Bishop de Korte explained.

The dispute eventually led to a suspension of the university’s faculty to issue ecclesiastical degrees, meaning that it could not issue degrees conferred as part of the training of seminarians and other Church officials.

“The background of the break with the theological faculty of Nijmegen in 2006 was the refusal of the faculty to amend its statutes to the ecclesiastical guidelines of the apostolic constitution Sapientia Christiana,” de Korte explained.

The failed merger soured the relationship between the university’s executive board and the bishops, especially after the appointment of Wim Eijk as Archbishop of Utrecht in 2008 and his election as president of the Dutch bishops’ conference in 2011.

Eijk is largely regarded as a theological conservative and his appointment as the primate of the Netherlands gave him more influence among his peers in dealing with difficult issues, such as the status of Radboud University.

Then in 2009, the Dutch bishops published a document on the application of Ex Corde Ecclesiae - Pope John Paul II’s apostolic exhortation on Catholic higher education - in the Netherlands.

The bishops’ document said that the majority of a Catholic university’s board of directors must consist of practicing Catholics, and that universities must try to appoint as many Catholics as possible in academic positions.

“If you read [Ex Corde Ecclesiae] you see that a Catholic university should, among other things, have a missionary function. It should lead and strengthen the faith, and make sure that the truth of Christianity and Catholicism is being defended,” said Lüthy, Radboud’s former dean of philosophy, theology, and religious studies.

“But that is increasingly difficult with the extraordinary secularization in this country.”

Technically, said Skertens, the university’s dean of theology, the Dutch bishops’ conference had the authority to appoint and dismiss members of the leadership board of SKU, the foundation overseeing the university.

But in practice, the board proposed candidates, and the bishops approved them. Until they didn’t.

“That led to a tension between them,” he said. “For years, the bishops had problems with the proposed candidates.”

In 2014, a board member of the SKU retired. The board nominated a replacement, but the bishops rejected her because she was not married in the Church. The board made another nomination, but the bishops rejected her as well, because she was not a practicing Catholic.

The bishops then put to the board their own list of candidates, all of whom were dismissed due to lack of qualifications or advanced age.

“It's not bad will from the university. It's not that we say: let's have no Catholics. It's just that we find, in this country, fewer and fewer engaged Catholics who also have all the necessary qualifications to run such a complex business as this university. So that's a classical dilemma,” Lüthy told The Pillar.

“When I arrived in the Netherlands in 1997, the country was already deeply secularized,” said Lüthy, who is Swiss.

“It seems that in the ‘70s the Church just crumbled, which means that our theological faculty was and is educating very few priests, very few vocations to the clergy, and it also meant that it was more and more difficult to get devout Catholics who were prepared enough to run the university.”

In 2017, a delegation from the university visited the Congregation for Catholic Education to plead their case. They argued that it was essential to have qualified administrators on their board, but said it was almost impossible to find quality candidates who were also practicing Catholics who met the approval of the bishops.

“The other issue you have is that after the merger of the theological faculties in 2006, the University of Tilburg became THE Catholic university in the bishops’ eyes — Faithful Catholics want to be there,” explained a Church official familiar with the case, who was not authorized to speak on the record.

“Radboud sort of became the wayward child whom no one wanted to be involved with. This meant that the faithful Catholics that were qualified enough to serve on the board simply did not want to.”

Start your day with Starting Seven - a daily news roundup in your inbox.

A widening rift

The stalemate reached new heights when the SKU announced in 2019 its intention to open a Transgender Care Center at Radboud University Medical Center (RadboudUMC), which created an even wider rift with the bishops.

“For the Church, the unborn life and the declining life both belong to God. I have always understood that the administrators of the Radboudumc felt the same way, yet they felt unable to guarantee that they would never, ever carry out an abortion or administer euthanasia. That has caused tensions for a long time,” Bishop de Korte said in an interview with Vox, the university’s magazine.

“The more recent transgender treatments have complicated the matter even further. The hospital connects the transgender care with the Catholic emancipation history of the university,” the bishop told The Pillar.

“According to the board of the RadboudUMC, the medical care for transgender [people] matches the support for vulnerable people in the peripheral society. It may be obvious that the bishops give another meaning to the notion of ‘Catholic emancipation,’” he added.

Some in the university community have added to criticism of the university's commitment to Catholic doctrine.

A medical student at Radboud who wished to remain anonymous told The Pillar, “The Medical Center makes it seem as if they only practice abortion and euthanasia because they are required by law, but in class and in rotations, the attitude is much different. It’s always discussed as a simple, valid medical option among many.”

The fallout over the transgender center complicated efforts to solve the board appointment issues.

In 2019, the board nominated four candidates. All four were turned down by the bishops’ conference. Because of the stalemate, the SKU had by 2020 only six board members, one too few to meet the minimum requirements of its statutes.

Eventually, the SKU took the case to the Enterprise Chamber, the highest court for corporate disputes in the Netherlands. On July 21, 2020, the court ruled that the SKU could temporarily appoint its own members without the bishops’ approval.

A week after the ruling, the bishops’ conference informed the SKU that they were rescinding the university’s “Catholic” designation, which meant that Radboud University could no longer be considered Catholic.

The decision was met with criticism from some members of the university community.

“I was very disappointed in the bishops’ decision,” Fr. Geelen told The Pillar. “I understand why they have a problem with the [Medical Center], but you can never shut the dialogue with the university. That is not Catholic. You cannot compromise your convictions, that’s very clear, and it should stay that way. But you cannot stop the dialogue.”

“They say that the university is not Catholic anymore, well, I’m here as a chaplain and I work with Catholic students. So where does that leave us?” he added.

The Vatican speaks

Despite the bishops’ decision, Radboud University still appears as a Catholic university in the Vatican’s 2022 directory. And in September 2022, an article in Italian media referenced rumors that the Vatican’s Dicastery for Culture and Education had told the Dutch bishops that it disagreed with the decision, prompting speculation that the bishops’ decision would be reversed.

The rumors were confirmed in November 2022, when the bishops were told during their ad limina visit that although they could remove the “Catholic” designation from the SKU, the Vatican still considered Radboud University to be Catholic.

“Rome sees Radboud University as something that belongs to the authority of the Holy Father,” Bishop de Korte said during a press conference in November.

“We had the right to terminate our relationship with the SKU, but Rome sees Radboud University as something that belongs to the authority of the Holy Father,” he continued. “In that sense, Radboud University is still a Catholic university.”

“The Vatican actually said that the Dutch bishops’ decree is valid: The SKU is not allowed to call itself Catholic anymore, but that this fact does not affect in any way whatsoever the Catholic nature of the university,” Sterkens told The Pillar.

“So, Rome found this beautiful, diplomatically skillful way to say that the decree is valid, but that the university has always been Catholic.”

The Vatican decision seems to align with canon 804 of the Code of Canon law, which stipulates that “even if it is in fact Catholic, no school is to bear the name ‘Catholic school’ without the consent of the competent ecclesiastical authority.

But since the Vatican’s decision was communicated to the Dutch bishops verbally, but not in any official written communication, the implementation of the decision has been left up to the bishops and the university.

At the same time, Bishop de Korte noted that both the university and the bishops’ conference see the controversial hospital as a distinct entity from the university itself — which could potentially simplify things from the university.

The medical center, which was the source of the most intense controversy with the bishops, has been administratively separated from the university, for purposes of financial liability.

“After the crisis between the bishops and the Radboud in fall of 2020 we now make a distinction between the Radboud University and the academic hospital,...[which each] have a board of their own,” the bishop told The Pillar.

“The conversations between the Church and the Radboud University only deal with the actualization of the relations with the university, not with the hospital.”

Now that the Vatican has spoken, the remaining question is not whether Radboud University is Catholic, but what kind of Catholic university it will be, in an increasingly secularizing environment without any functional oversight from the bishops.

“In the 80s, 37% of [Dutch] children were baptized in the Catholic Church, now it is less than 3 percent. Thirty-seven or 38 percent of civil marriages were solemnized in the Church [in the 1980s]; last year, fewer than 1% were. It is nothing less than an implosion,” Sterkins told The Pillar.

At Radboud University, he said, “[w]e have a student’s chaplaincy, we have a faculty of theology, we have the Titus Brandsma Institute that studies Christian spirituality, we have the Institute of Eastern Christianity and the Institute of Missiology. And we have an institute of study of religion and policy development which has been doing since the 1960s the official statistics of the Catholic Church in the Netherlands.”

“So, we have all these institutions that have quite an impact. But I can imagine that in a very secular context, a university that is publicly funded should give a service to the whole society. It is much like the case of Catholic universities where there is only a minority of Catholic students,” he continued.

The university is currently undergoing a process of reviewing its Catholic identity as it prepares for its centennial celebrations this year.

“These conversations are going according to plan. In the meantime a Laudato Si Institute was founded and there are also plans to raise an advisory college in which also the local bishop will have a place,” Bishop de Korte told The Pillar.

“In the future, however, the bishops will have no direct legal influence anymore,” the bishop continued. “The relationship between Church and university will be one of continuous dialogue and advice.”

Lüthy, the former dean of philosophy, theology, and religious studies, said he believes more cases like that of Radboud could arise in the future, given the secularization of many Western countries.

“The Netherlands is perhaps the most secularized country in Europe,” he said. “So, what does the Catholicity of the university mean in this environment? It meant a number of things in the past, including that the supervisory board was approved by the bishops. But once this isn’t the case, what does it exactly mean to be a Catholic university?”

“I think that the Vatican realizes full well in which situation the Netherlands is,” he added. “We are, in a way, a test case for how the Vatican will deal in the future with Catholic universities because we are further than all the countries, but the tendency to secularization is ubiquitous.”

📰