From 6 to 6,000 - Meet the bishop of the growing diocese of Estonia

"The Catholic Church in this whole area is small, but it is a beacon of hope."

On September 26, the Vatican announced that it raised the apostolic administration of Tallinn - covering the whole country of Estonia - to a diocese.

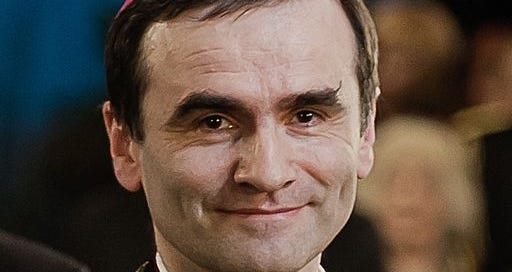

Bishop Phillipe Jourdan, who has been the apostolic administrator until now, will serve as the diocese’s first bishop.

Jourdan was born in Dax, in the French Basque Country, and was ordained a priest of Opus Dei in 1988. He served as a priest in Madrid and Paris until he became the vicar general of the Apostolic Administration of Estonia in 1996. He was ordained a bishop in 2005 to become the apostolic administrator.

The Apostolic Administration of Estonia was founded in 1924 and covered the whole of the small Baltic nation. The new Diocese of Tallinn, based in the capital, will cover the same territory.

Estonia is one of the less religious countries in Europe --- about 60% of Estonians profess “no religion.” Due to 300 years of Swedish rule, the country is traditionally Lutheran, with a large Orthodox minority, due to its closeness to Russia and the fact it also was under Russian rule in the 19th century.

Estonia was one of the last territories in Europe to be reached by the Catholic Church.

The country was conquered by the Teutonic Order during the Livonian Crusade in 1227, meaning it had about 300 years of Catholic presence before the Reformation reached the country, comparably less than most European countries.

When Catholicism was legalized after the country’s independence in 1918, the Church started to grow. However, this growth was halted with World War II, as thousands of Estonians were deported to Siberia and other parts of Russia, including the then-bishop Eduard Proffitlich, martyred by the Soviets in 1942 and now a Servant of God.

The result of this complicated history is that Estonia is the country with the fewest Catholics in Europe (or the second-fewest after North Macedonia, depending on the statistics). Only 15 priests serve the whole country.

However, the country’s Catholic Church has had a steady growth since the ‘80s when restrictions against religion were slowly loosened.

To better understand the situation of the Catholic Church in Estonia and the creation of the new diocese, The Pillar spoke with Bishop Philippe Jourdan of Tallin. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Why did the pope decide to create this new diocese?

We had been waiting for 100 years for this decision to create a diocese, because we were an apostolic administration before.

So, why now this change? Well, for historical reasons. As in all the countries of Lutheran Europe, the Catholic Church disappeared for three centuries or so. When Estonia was under Swedish power, Catholicism was banned.

Then, it came under the power of the Russian Empire, where Mass could be celebrated, but with some restrictions. One of the restrictions was that all the Catholics of the Russian Empire had to be in a single diocese based in St. Petersburg, because that was the condition that the czar gave the pope to allow the Catholic Church to continue working in the empire.

Then came the independence of Estonia in 1918, and very quickly the pope recognized the new country and decided --after 400 years-- to give it a Catholic Church of its own in 1924.

But since the Catholic community at that time was so small, the pope gave Estonia a provisional status of apostolic administration, which is a special status given to a local Church when there are particular difficulties, such as, precisely, the size of the local community. Of course, 100 years ago, people could not have known that soon there would come 50 years of Soviet occupation.

None of the other northern Lutheran countries were under Soviet power. So, in a way, they are 50 years ahead of us. That's the difference - Estonia is the last country in Lutheran Europe to have a Catholic diocese. So, we can say that with the pope's decision, the return of the Catholic Church to northern Lutheran Europe is complete, at least from the canonical point of view.

It is quite significant. One can say that after centuries after being totally uprooted from Northern Europe, the Catholic Church is now fully back.

One of the differences between an apostolic administration and a diocese is that the apostolic administrator governs the diocese in the name of the pope, while the bishop of a diocese governs his diocese in his own name and in union with the pope. It can be said that the local Catholic Church in Estonia is no longer a mission of the Holy See. People here have viewed this change as the pope putting the Catholic Church in Estonia in our own hands.

It is something quite important for us, and many people have congratulated me after that. Many Catholic bishops, but also from our separated brethren, Lutheran bishops, Orthodox bishops who have seen that it has been a long journey, but it is an important moment.

We are the only Lutheran country in Northern Europe that, in addition to being Lutheran, has also had to be Soviet for 50 years. That is another issue to overcome.

The number of Catholics is certainly small, but the country is also small. And it's also the country in Europe with the smallest percentage of religious people.

Now, if you ask me if it’s the most secularized country in Europe, I’m not so sure. Statistically, it is. But on a practical level, I don't think there is such a big difference with other northern European countries. In fact, while in other countries the number of believers keeps decreasing, in Estonia it has remained more or less stable since the fall of the Soviet Union.

And the number of Catholics has been increasing. It is one of the few churches that has grown in Estonia since the end of Soviet times. We are not yet 1% of the population, but we are close. You know how they say that making the first $1000 is the hardest, it's the same here. The first percentage point is the hardest.

A German academic once did a doctoral dissertation on the Catholic Church in Estonia in the 20th century, and he said that in the 1970s there were five or six Catholics in Estonia. I’m not misspeaking. There were not 50, there were not 500: there were five, like the fingers of one hand.

A couple of years ago, I was invited by the Baptist church, which has been established for hundreds of years in Estonia, to speak to their pastors about the Catholic Church in Estonia. Then, an elderly pastor came to me and told me that he remembered very well what the Estonian Catholic Church was in the ‘70s and, seeing what it is today, we have many reasons to thank the Lord for what He has done with the Catholic Church here in Estonia.

It is true that we are a small Church, but, given the history of the country, the strange thing is not that the Church is small, but that there is a Catholic Church in this country at all. The Church is growing little by little. Every year we have a good number of people asking about the Church or asking to be baptized or welcomed in the Church.

What is the Church in Estonia like today?

The Church is small but very diverse. Most Catholics are Latin, but we also have two Ukrainian Eastern Rite parishes. Since Soviet times, there is an important Ukrainian community here, so we started a parish for them.

Now, many Ukrainian refugees have also come here due to the war. Proportionally, Estonia is the country in the European Union with the highest percentage of Ukrainians, they are 6-7% of the population. So, this year we have also started another parish for the Ukrainians in the south of the country and we already have some Eastern rite priests to serve them.

The Catholic Church here is relatively well known for its schools. Until 30 years ago, there were no private schools in Estonia, because it was under the Soviet communist system and there had never been a Catholic school. So, here we opened a Catholic school first in Tartu, which is the university city, and then in Tallinn, which is the capital, and both are working very well.

Because of the country we live in, they are not schools for Catholics. Most of the students are like the country itself. They are not Catholic, and many are not even Christian, but the parents want their children to be educated in a Catholic school.

What many people know about the Catholic Church is what they know from the Catholic school, of course. For us it is a means of evangelization. There are students who have become Catholics after graduation and that has been also the case for a good number of teachers.

Catholic schools are, for the population, the face of the Catholic Church. And that is important.

The Lutheran and Orthodox churches have followed us because now Christian schools have become very, very popular in Estonia, for some reason, so there has been a growth in Christian schools in the last few years.

I think this is a positive thing. It’s difficult to talk with the government with only two Catholic schools because sometimes the government is not very much in favor of our way of seeing things. However, if we are a good number of Catholic, Lutheran and Orthodox schools, we already have more weight to ask for state aid and to talk face-to-face with the authorities.

The number of Catholics is always a bit difficult to determine. The last census says that in Estonia there are about 10,000, or 0.8% of the population. The truth is that I think there are a little less, between 6,000 and 8,000. Before World War II, there were 2000 of us. Then, with the Soviet period and all the persecution, the exiles to Siberia, there were five Catholics in the ‘70s, and in the early ‘90s we were 3,000.

We have 15 priests in the whole country, which is not much, but they are mostly young. In Soviet times, there was only one priest for the whole country. There are now also 18 religious sisters in various cities.

There are the Missionaries of Charity, whose history is very beautiful.

When the Soviet Union fell, Mother Teresa said, “Well, since there were 15 Soviet republics, we must put here the 15 mysteries of the Rosary.” Fifteen mysteries, because there were no luminous mysteries at the time. So, she wanted to start a community of her missionaries in each former Soviet republic and each one has a mystery of the rosary assigned to it. In the case of Estonia, it is the Ascension of the Lord.

Then, there are the Brigidine sisters, which is a typical congregation of the northern countries founded by St. Brigid of Sweden, and they have a special charism to engage with Lutherans. And they do very good work in Tallinn. They have a large convent where they also have a guest house, for pilgrims and for travelers. There is another Congregation that takes care of the Catholic school in Tartu.

As far as the men, we have two Dominicans. There is also the Neocatechumenal Way, which has a small seminary in Tallinn, from which two priests have already been ordained. The students come mostly from Poland or Belarus and similar countries and are ordained here.

We have Fidei Donum missionary priests, but one problem with Estonian is that if a priest comes here over 35 years old, he will learn some Estonian, but he will not speak it well. So, the priests who come must come young. Fidei Donum seminarians don’t exist, so having young people who are trained here and learn the language from a young age is very important to do a deeper apostolic work.

Additionally, Opus Dei has been present since I arrived in 1996 because the Holy See asked the prelate to bring a priest of the Work to be the vicar general in Estonia, because at that time the apostolic administrator was the nuncio for the Baltic countries, who lived in Lithuania.

But the prelate at that time, Don Javier Echeverría, said that it is not our spirit in the Work to send a priest alone to an unknown country. So, he said that, if we sent someone, we would also start a center for men and one for women to have a normal start of the apostolic work of Opus Dei, and so that I would not be alone. So, we have about three Opus Dei priests and some laypeople of Opus Dei in the country.

You had been serving in Paris. Why were you chosen to come here?

At the time, I was working in Paris, and the Holy See asked Opus Dei for a priest to be vicar general, with the condition that this priest would speak English and Russian. They were not going to get a priest who spoke Estonian, of course, but with those two languages you could start because they are the second languages of many people.

It turns out that before I became a priest, I was a road and bridge engineer, and many French companies wanted to do work in the Soviet Union, which was slowly opening itself to the world. When I was studying, many professors told us to learn Russian because it would help us to get jobs to go to construction projects in Russia. So, I learned Russian.

Of course, I spoke very technical Russian, public works Russian. I had no idea how to talk about confession or prayer in Russian, but I could perfectly explain to you how to prepare concrete.

Then in December '95, I got a call from the nuncio, and he asked me if I was willing to come to Estonia and six months later, I was here.

In the beginning, celebrating Mass in Russian with only the vocabulary of public works was a bit complicated. I preached with what I knew. So, I was talking about laying foundations and building bridges (laughs).

People told me that it was interesting that Catholic preaching was very construction-oriented, but it just was because I didn't know how to say anything else. Then little by little I learned more.

What does apostolic work in Estonia look like? Fifteen priests for 6,000-8,000 Catholics scattered throughout the country doesn’t seem like much.

Although we are few priests, it helps that it is a small country. Estonia is about the size of the Netherlands.

Here the Catholics are in many cities, like in the beginning of Christianity. So, the priests are quite scattered and a bit isolated. I go to see them often and we all meet monthly. We try to make sure that no priest lives alone, because otherwise it is a bit hard, especially in the long Estonian winters.

In a country like ours the priest can't just sit there in his church and wait for people to come, because they will never come. It is a country of Catholic diaspora. So, you always must go out and look for people, organize catechism classes to explain the faith to people who want to know about God. Our work is to look for people day after day.

I believe that this is also the future of the Church, a Church that is a bit of a minority, as the pope said in Belgium, which was a Catholic country par excellence, but now it is a minority Church. The future is taking care of each concrete person, of each catechumen, of each Catholic. When John Paul II was in Finland many years ago, he told the priests that they had to make the effort to go to the last Catholic, even if he was the only one in the town.

The Church grows. And I think that when we talk about Estonia, but also about Finland, Sweden, Norway and so on, the Church is still small, but we can say that it is the only part of Europe where the Catholic Church has grown a lot and continues to grow. Of course, it is growing from almost nothing. But now it is a significant part of the society, not only in Estonia, but also in the other countries. And well, there are many cities in Scandinavia where on a Sunday there are more people in the Catholic Church than in the Lutheran Church.

So, the Catholic Church in this whole area is small, but it is a beacon of hope.

What does evangelization look like in a country as secularized as Estonia?

Evangelization is one-to-one. When I was ordained bishop, an Estonian whose family had emigrated there after the Soviet period came from the United States. He was a very old man at the time and was part of the first Estonian family to convert to Catholicism.

He told me that he remembered as a young man his mother telling him to be quiet on Monday evenings because in the house was Eduard Profittlich, the first bishop in Estonia, who was later martyred in World War II and, God willing, will be the first Estonian Blessed.

It turns out that this bishop came personally every Monday to teach the catechism to his father, who was a doctor. This worked, because his family persevered in the faith thanks to this personal care… I believe that this spirit of caring for each one is essential for evangelization in this country.

At the last Easter Vigil, we received about 30 people into the Church, but there are also people who are baptized or received at other times of the year, so there are more. And I have also noticed that lately the people who come to know the Church or to ask for baptism are younger. Before the average age was close to 40 years old, now people come between 20 and 30 years old.

It is important to accompany people because normally the people who are baptized or received in the Church are the only Catholic or even the only believer in their family, so it is important to support them, not only to prepare to be Catholic, but to persevere and grow in faith.

Christians who make regular confession and spiritual accompaniment a habit, persevere and grow in the faith. Those who do not, well, usually do not persevere or have many difficulties.

How are relations with other Christian communities in the country?

They are very good. We have a council of churches here. The president is the Lutheran archbishop, I am the vice-president. We work a lot together on relations with the state, especially when there are laws on marriage or on life that are not very good. There we go, Lutherans, Catholics, Orthodox, Baptists and other denominations, visiting politicians giving a common witness of faith.

Once a Lutheran bishop told me that the persecution under the Soviet Union has brought us together; the pressure of the Soviet power made us much more united, and we have helped each other much more ever since. We have very good ecumenical work.

The Catholic Church has today in the whole of Northern Europe an impact and an influence that is much greater than its size. I even remember an Estonian Lutheran archbishop who told me, “Look, when there are discussions about moral issues, the first thing we do is to see what the Catholic Church says about it, because we don't have experts on every issue, on every question.” He tells me that on these moral issues, the Baltic Lutherans feel closer to the Catholic Church than to the Lutheran Churches in the North.

Many people from the other churches congratulated me for the new diocese of Tallinn, which is a sign of the brotherhood between the Christian communities. I also think that especially the Protestants have a certain nostalgia for the union and for the sacraments and it is something that is becoming more and more noticeable.

With regards to the government, God works miracles, but we do not (laughs). Last year there were elections and now we have the most progressive government in this country, and they wanted to pass a gay marriage law almost immediately.

The Lutheran archbishop, some others, and I spent May and June visiting every politician imaginable: ministers, heads of parties, parliamentarians. We met with everyone, of all political tendencies, explaining our arguments. The conversations were sometimes a bit tense, but always polite.

I tell you that we do not do miracles because in the end the parliament passed this law, but it was clear that the Christian churches are very united on this issue, that we are all in favor of marriage as a union between a man and a woman. Certainly, we did not achieve what we wanted, which was not allowing this law to pass, but we clearly made known the position of the Church and that the Church defends this not because we are conservative and old, but because we have a clear and rational position on these points. I believe that in the long run this will bear fruit.

What do you envision for the future of the Catholic Church in Estonia?

God is the one who decides. The Catholic Church in this country is appreciated, and we know how to give answers to the questions that many people ask.

Sometimes other churches have more difficulties to give those answers. I think we have been able to show the Church as something attractive, despite so many years of Soviet propaganda, as something that makes you have a better life and be happy.

The pope's visit six years ago helped a lot. People did not expect such a close and direct pope. The pope has a talent for [reaching] non-Catholics and here he did it with many people who had never set foot in a church before.

We were five or six, now we are 6,000 or more. At this rate the whole society will be Catholic eventually (laughs).

I don't think I'll ever tire of the Pillar's 'Interviews With Priests and Bishops From Tiny Catholic Populations'. At this point it ought to be an official series. Anyways, Bishop Philippe seems to be doing the Lord's work, and I hope continues to find success in his mission. It's especially encouraging to see, in Estonia as in Finland, greater unity between Catholics, Lutherans, and Orthodox. It's a sign of hope for future unity, if nothing else.

This is the kind of thing that gives me hope, genuine hope, which is not optimism. So much could be learned from this model. I second Joseph's call for a series of these. Truly inspiring.