For Joan of Arc, history 'bent' toward justice

In France, and for the Maid of Orleans, history has an 'Arc'

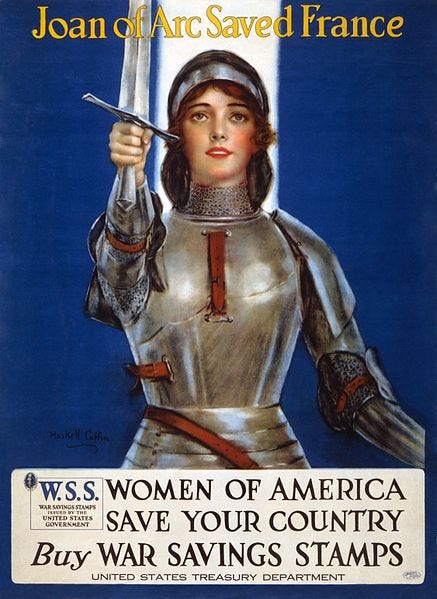

Tuesday, May 30 is the feast day of St. Joan of Arc, who was burned at the stake by secular authorities on May 30, 1431, after a Church court found she was guilty of heresy.

Few saints begin the journey to eternity with a declaration of heresy.

But while St. Joan of Arc was exonerated of wrongdoing within 25 years of her death, she was not canonized until 1920, almost 500 years later.

The path to her canonization mingles Catholic devotion with the political and cultural history of France. And The Pillar brings you the story.

—

If you remember medieval history from Shakespeare’s plays, you know the story of St. Joan of Arc features in the aftermath of the campaigns of Henry V.

In the aftermath of the English King Henry V’s victory at Agincourt, he married Catherine, the daughter of defeated French King Charles VI, with the goal of their children ruling both England and France. In 1421 the couple did soon have a son, also named Henry — but Henry V died the next year, just two months after the defeated French King Charles VI.

His death left a messy and disputed situation.

Half of France — including the capital city of Paris — was occupied by English armies who now considered the one-year-old Henry VI to be king of both England and France. But the surviving son of Charles VI, also named Charles, felt that he was a much more appropriate candidate to be King of France, being 18 years older than the infant prince Henry and also, well, French.

Charles faced a key difficulty, however, in that he did not control the city of Paris nor did he control the city of Reims, in whose cathedral kings of France had traditionally been crowned. And while Henry VI was in no position to lead armies at his tender age, his uncles the Duke of Bedford and the Duke of Gloucester were continuing Henry V’s conquest of France, city by city.

Joan grew up in the context of a country riven by warring French and English armies.

At the age of 13, in 1425, Joan began to have visions of St. Michael the Archangel and also the virgin martyrs St. Margaret of Antioch and St. Catherine of Alexandria. Based on those visions, Joan took a vow of perpetual virginity and became convinced that she was called to free France from the English invasion, and to shepherd Charles VII to the French throne.

In the chaotic and devout climate of medieval France, a number of popular prophecies had circulated that the country would be liberated by a virgin.

When 16-year-old Joan first attempted in 1428 to convince local French military leaders of her calling, she was ordered home. But the next year she convinced a local nobleman and garrison commander, Robert de Baudricourt, to present her to Charles VII’s court.

The French prince was impressed by his first interview with now 17-year-old Joan, and after a group of theologians he assigned to examine her rendered a verdict that she was a good Catholic, Charles provided her with armor, a sword, and a banner and sent her to join his forces in the besieged city of Orleans.

Joan rallied faltering morale among the defenders and personally accompanied leading French troops in a series of counter-attacks which caused English forces to abandon the siege of the city within less than two weeks of Joan’s arrival.

Over the next two months, Joan encouraged French commanders to pursue an aggressive strategy.

Holding aloft her banner, Joan visibly accompanied front line soldiers during a series of engagements in the Loire, ending with the Battle of Patay, at which English forces were routed and retreated to Parish.

That victory allowed Charles to enter Reims unopposed, where he was crowned on July 17th, 1429, just two-and-a-half months after Joan had joined the French Army.

But the coronation of Charles VII marked the high point of Joan’s military success.

After the coronation, King Charles VII became focused on reaching a negotiated settlement with his enemies, and his commanders listened to Joan less.

During the summer, an attempt to drive the English out of Paris failed, despite Joan’s continued front-line support.

The following spring Joan was captured and turned over to English authorities, who put her on trial for heresy in Rouen and burned her at the stake on May 30th, 1431, at the age of 19.

Getting rid of Joan did not solve the military and diplomatic problems of the English, however. Over the ensuing 20 years, Charles VII succeeded in peeling off their Burgundian allies and inflicting a series of battlefield defeats, which by 1450 reduced English control of France to Calais.

Charles also supported efforts to clear Joan’s name. As soon as French forces regained control of Rouen, where she had been tried and executed, he supported a series of ecclesiastical trials which re-interviewed witnesses.

In 1456, 25 years after Joan’s death, a final trial sponsored by Pope Callixtus III found Joan innocent of all charges, and her original trial unjust and deceitful.

The young woman of peasant origins who helped crown a French king was not without recognition in the wider Church in the following years.

But while Orleans had an annual festival in her honor, there was not a broad movement to canonize her.

Her mother and brothers had been active in the efforts to have her name cleared of heresy, but she did not have the backing or a religious order to further a cause for her sainthood. The French monarchy did not put resources behind raising a peasant girl to the altars when St. Louis IX was already available for intercession for the kings of France.

It took another set of paroxysms in French political and Church history to bring Joan of Arc again to the foreground of French Catholic life.

Joan’s legacy came under attack during the French Revolution.

In 1793, her annual celebration in Orleans was forbidden, and only restored by Napoleon 10 years later.

But with the restoration of the French monarchy, Joan of Arc served as a reminder of French military success, which was also tied to the restoration of the French monarchy and the close connection between that monarchy and the state. For a country recently defeated at Waterloo, this was an especially popular piety to embrace.

Those factors made Joan a powerful symbol for France, at a time when the monarchy bore with it a legacy of defeat and foreign influence while French military success was tied with the radically secular Republic and ambiguously secular Empire.

As important, Joan was also a true daughter of the people, rising from peasant origins. In a divided country, the story of the peasant girl turned saintly national hero provided something for everyone.

Bishop Felix Dupanloup of Orleans was a major proponent of Joan’s cause for more than 20 years, and in 1869 petitioned Rome to begin beatification proceedings for her.

The next year, France was invaded by Prussia in the Franco-Prussian War, and suffered a humiliating defeat, losing the region of Alsace-Lorraine to Germany. As French Catholics worked to reconcile their loyalty to the Church with their national obligations to the secular Third Republic, the figure of Joan of Arc — who restored France during a period of invasion from abroad — seemed all the more relevant.

During the late 1800s there was a flurry of cultural interest in Joan’s story. French nationalist poet Charles Peguy wrote two plays about her, one before and one after his reversion to his Catholic faith. Secular French author Anatole France wrote a biography of Joan in 1908. And in the English-speaking world, American atheist author Mark Twain wrote a surprisingly sympathetic novel about Joan’s life, “The Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc,” in 1896.

St. Therese of Lisieux was also inspired by Joan. In fact, one of the surviving photographs of Therese is of the one young French saint dressed up as the other in a play about the medieval saint which Therese composed herself.

When Joan of Arc was finally beatified in 1909, devotion to the peasant girl turned French national hero provided French Catholics with a means to show their patriotism and deep connection with the country. That was an important potential path towards healing in Third Republic France. Tensions were high between Church and state In the aftermath of both the Dreyfus Affair — in which a Jewish army officer named Alfred Dreyfus had been framed for and then exonerated of treason, with prominent Catholic groups having insisted upon Dreyfus’s guilt well past the point when it became clear he was innocent — and the Affaire des Fiches — in which the secularist Minister of War had used the Freemasons to compile a list of army officers who attended mass and deny them promotions.

Some French Catholics even questioned whether it was possible to be a Catholic and support the French Republic at the same time. Church authorities had sought ways to bridge the gap, and Joan, with her peasant origins, deep devotion, and distance from current political divides seemed a perfect figure to do it.

Joan of Arc was thus in the forefront of the French Catholic imagination when France was again invaded by Germany in 1914, and her intercession was often sought by soldiers at the front.

Devotion to the Maid of Orleans continued to build through the war, until she was at last canonized by Pope Benedict XV in 1920.

In 1922, Pope Pius XI declared St. Joan of Arc one of the patron saints of France.

Mark Twain considered "Joan of Arc" his best work.

Excellent article.