Copyrights and Confraternities: A history of ‘official’ American Scripture translations

How did the New American Bible translation come to be?

The U.S. bishops’ conference made headlines last month, over a memo which reminded bishops that if parishes want to reprint scripture in bulletins or worship aids, they need to pay USCCB licensing fees for the privilege.

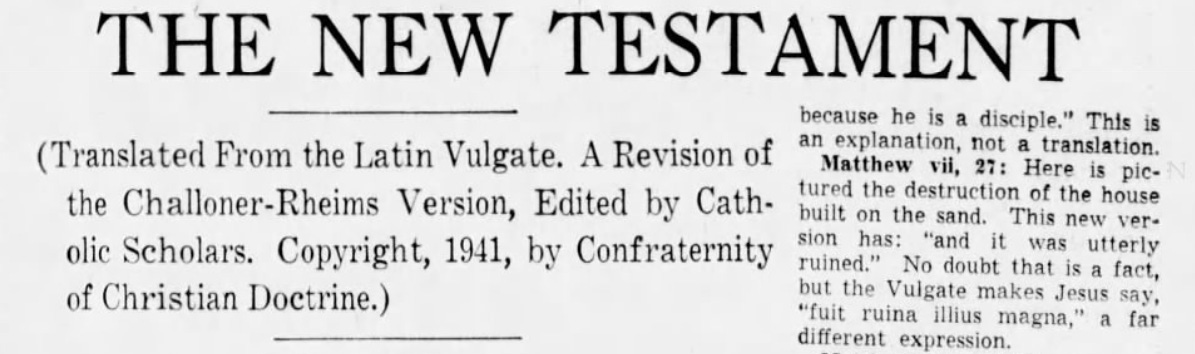

The U.S. bishops’ conference holds copyright to…