Concerns about CL culture persist after abuse allegations made public

“We need to really pick apart our attitude, our culture deeply.”

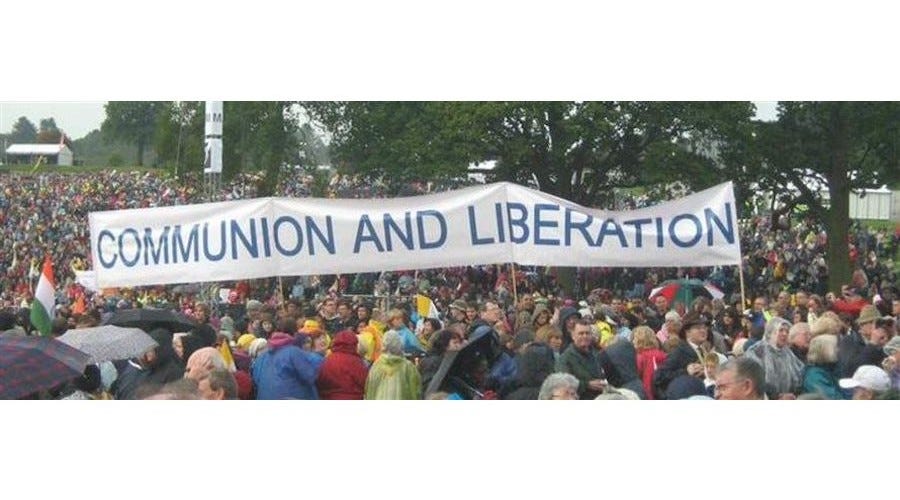

After the ecclesial movement Communion and Liberation acknowledged abuse allegations made against its former U.S. leader, alleged victims say the movement has not addressed elements of its culture which, they say, allowed abuse to occur unchecked.